Would the real Australia please stand up? Are you a tropical paradise of blue skies and golden beaches, the Great Barrier Reef, koalas and kangaroos? Or are you the perilous continent of venomous snakes and enormous spiders, dense bushland and parched desert where travellers venture and never return?

It’s clear which scenario thriller and crime writers are drawn to. Australia has long been mythologised as a dangerous exotic land, the landscape presenting the ideal setting for an eerie thriller not unlike that of Nordic noir.

In reality, how frightening is it to live here? On TikTok there’s an avalanche of clips showing gigantic Australian spiders; there’s a frisson of excitement in the thousands of comments generated. While the spiders aren’t actually that large (the angles exaggerated for horrific effect), it’s a fact that we’re home to the world’s most venomous, the Sydney funnel-web. I’ve seen plenty of Huntsman and Redback spiders at home, and simply give them a wide berth.

Most of the world’s most venomous snakes live in Australia (85%), although the only snake I ever encountered was during a visit to Canada.

Australia is one of the most shark-infested countries in the world too (behind the US). The yearly worldwide shark attack summary (yes there is such a thing), says there were 15 “unprovoked incidents” in 2023.

And let’s not forget the temperature. In summer, temperatures can soar to around 40°C (104°F). The highest temperature ever recorded was 50.7 °C (123.3 °F), in 1960 in Oodnadatta, South Australia – where my father in law was born. Is it any wonder that the Australian population clings to the cooler coastline? About 87 percent of the population lives within 50 kilometres (31 mi) off the coast. We’re like people hovering near a doorway for a quick escape.

Roads are closed and towns cut off when we’re ravaged by bushfire or flood. This sometimes means arduous detours (in the thousands of kilometres) for food and other deliveries; major routes such as the Nullarbor Highway can be shut, and travellers forced to hole up in roadhouses for days.

Australians are well versed in the rules of outback driving. If you break down; never abandon your car. Always pack plenty of water. Share your travel plan with others, so if you don’t turn up on time, they know to raise the alarm.

You can’t rely on a cell phone in the outback – not to call for help, or to help you navigate. Most of Australia’s land mass has no mobile coverage at all. Like the population, it hugs the coast.

But it’s important not to demonise this beautiful country, its flora and fauna. Every living thing plays a part in the ecosystem, and in this climate crisis the last thing we need is an extermination attitude. It’s also important to reflect that Australia was colonised, the indigenous did not cede this land, and there have been successive waves of immigration. To what extent did the colonisers and bewildered immigrants contribute to the lore of a frightening Australia?

My own parents arrived here as children – my mother from Finland, my father from The Netherlands. Even though I was born here (in the world’s most isolated capital city, Perth), I’ve always felt apart. I wonder how my parents influenced that; English is their second language, they had to adjust to the climate, the culture, the distance from everything they knew. I inherited a sense of being an alien here, observing but not participating. But perhaps that’s part of being a writer…

I’ve had my fair share of roadtrips – another popular setting in Oz literature, and in fact the inspiration for The Rush, my outback thriller.

Like many teens, I left home to study at a capital city university. Whenever I wanted to visit family or friends, I faced a four-hour roadtrip north. I passed through many tiny country towns, but for the most part, the scenery was fields of crops or plains of orange sand. Eventually, I returned home and worked for a federal politician and there were more roadtrips. Our electorate took up an incredible 92% of South Australia. That’s 904,881 square kilometres (349,377 sq mi). Still later, I worked for the South Australian Tourism Commission. As a website editor and writer, I travelled over the state, absorbing its beauty and trying to translate that to the online page.

(It’s an irony not lost on me, that many readers of The Rush have declared they’re “never” coming to South Australia or never camping in the outback. I believe it’s said with tongue-in-cheek, but to think of all the effort I put into attracting tourists, and now it’s coming unstuck…)

With all of this seeping into our psyches, is it any wonder Australian writers have produced haunting thrillers that leverage the landscape? Like Jane Harper’s The Lost Man, set on a vast cattle property in Queensland, and where in the opening scene a man has died of exposure and dehydration. There’s Shelter by Catherine Jinks, No Country for Girls by Emma Styles, and Out of Breath by Anna Snoekstra – all exploring Australia’s secluded pockets, remote from help or technology, high on risk.

The film world has mined similar territory, with movies such as Picnic at Hanging Rock (an eerie school excursion into the bush, where two students and a teacher disappear); Mad Max (on dystopian outback roads); The Reef (young people terrorised by a Great White Shark); and another Ozploitation example in The Boar (a family stalked in the outback by…you guessed it).

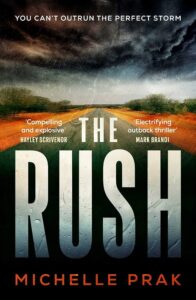

The Rush draws on many of this island’s dangers and myths, as well as my own decades of remote driving and unsettling experiences. It follows four young people on a roadtrip from Australia’s south to north; Adelaide to Darwin. Rather than the quintessential outback experience of heat and sunny skies, they encounter unseasonal rain and flooded roads. My characters quickly learn that the world is very different beyond their suburban cocoon.

And I hope, rather than deterring people, that such stories can captivate and actually attract tourists. That’s what occurred – believe or not – after the worldwide success of Wolf Creek, the 2005 horror film about three abducted backpackers.

If you do make your way down here, come say g’day.

***