I’d only been working for the British government for a few days when I met my first spy.

My new job was counter-terrorism communications, so I’d already had my background thoroughly checked before I ever stepped foot through the secure glass doors, and I’d thought that part was over when I first met Eve in the little kitchen at my office. I worked in one of those enormous London buildings that take up a full city block and hold thousands of desks. I met someone new every day and I wouldn’t have noticed her at all, except she stopped me to ask for help. She was new, she said. Working in the legal department. And did I know if everyone had their own cup or if people shared? A few days later I ran into her in the coffeeshop I went to every morning. Two days after that she was in the office canteen during my lunch break and we ended up sitting together.

She was a little younger than me, around twenty-eight, with wide blue eyes and a quick wit. One of those people you confide in without meaning to.

She asked lots of questions about my family, my history – why had I moved to England from the US? Why had I decided to work for the government? Happy to have made a new friend in this big, anonymous workspace, I chatted away about everything, right up until she disappeared.

And I mean, really disappeared. Her email evaporated from the computer system; her desk phone didn’t work anymore. She was gone.

When I asked around, nobody seemed to have ever seen her except me. It was as if I’d met a ghost.

A few days later, I was given my first serious project working with intelligence officers. Doors that had been closed to me before, opened. That was when I realised Eve had been a spy. And that my background check now really must be complete.

It was the first time I understood where I was working, and who I was dealing with. Before then I’d been a journalist and an editor, but I was in deep water now. On the inside of a world I didn’t understand at all.

The fact that I worked for the government was a complete accident. Someone who had known me at a previous job got in touch out of the blue, and said she was looking for someone who could write about counter-terrorism and ‘not get scared’. She knew I’d been a crime reporter, and she thought I might be able to handle the pressure.

The early 2000s were dangerous times. The July 7th bombings on the London underground had recently occurred when I first started work. Back then, I wouldn’t take the Tube at all – none of my friends did. We walked everywhere or took buses, too anxious about a possible attack to mind the length of a journey. My job was to convince spies to talk to the public and tell them all they were doing to fight terrorism. The only problem was, the spies didn’t want to talk to anyone.

I had long meetings with stern people from various intelligence agencies, who would listen to me explain about social media, live streams, and websites until I’d exhausted myself. No matter what I suggested, the reply was always the same. “No.”

“You should go on Facebook!” I would say. “It could completely change your image. You can talk to the public directly. Let them see that you’re just normal people doing a difficult job.”

“Good lord, no,” a counter-terrorism official told me with absolute horror. “What an awful thought.”

They didn’t want a website. They didn’t even want to have an email account. They didn’t want to talk to the public at all. Ever.

It’s not hard to understand why, of course. Spies live in the shadows. Secrecy is essential to their work. Anonymity is what keeps them safe. Also, they know the internet is a two-way street. If they could talk to the public, the public could talk back. If they were on social media, they could be hacked. If they had an email address, it could be phished. They understood this long before such things became infamous and common.

Everything I was offering them would have introduced vulnerabilities into their world, and they would never allow that.

If they had their way, nobody would know anything about them. Even me. I worked in their office, and yet I never really could be certain who was a spy and who wasn’t. After all, nobody ever walks up to you and says, “Hi, I’m Jason. A spy.”

They say, “I’m James from Logistics.” Only there is no Logistics. And James isn’t his name at all. But you figured that out later. In the moment, it all seems perfectly plausible. Everyone is so believable and normal. But everyone is lying and normal is not a thing there. And you never know anything.

It creates an environment where everyone is suspicious of everyone else. Everyone wonders if you’re a spy but no one ever dares to ask.

It’s like walking on shifting sands. The deception over little unnecessary things – I still don’t know if anything anyone ever told me back then was true – is wearing. And even spies don’t always know if the person they’re talking to is telling the truth. They’re suspicious of everyone.

This isn’t James Bond spying, all martinis and ball gowns. This is gritty, feet on the ground, hands in the dirt, spying.

One of my main jobs was helping out with real-life training, when intelligence, soldiers, and police would go deep into the countryside and game out an attack. To do this, they would stage an attack. Then they figure out how it blew up and how to stop it blowing up next time. It’s both incredibly simple and quite extraordinary.

These spy training events are still the most astonishing things I’ve ever been part of. They can involve thousands of people, and government officials at the most senior level, all decamping to the muddy countryside, some of them to stage a terror attack, and the rest of them to try to stop it.

The simulation I remember most clearly took place in a very quiet village in Wales. The government blew up a fake chemical factory on a Friday afternoon, and the game was on. Police, counter-terrorism, MI5, the Army, ambulance services, the Coast Guard – all were there to react to the series of attacks that were simulated over the course of three days.

I was part of a team playing the press – writing vicious articles about the failures of the government and the police to find the terrorists and bring them to justice. These were then prominently displayed on the computers of everyone taking part in the simulation. If I pulled my punches in an article, someone from Cabinet Office would call me and politely suggest I could try harder. “I don’t think you’re really hitting him below the belt enough,” a very posh voice informed me one afternoon, after I’d written an article about one government official. “I suggest you say that he’s failing to appropriately inform the public, and that it appears he’s losing control of the situation.” He added brightly, “Be as horrid as you like. All very useful.”

I did as he ordered, wincing as I described one of the heads of my own department as “failing” and “weak”.

The next day in a mock press conference, that official shouted at me furiously, “I believe the press needs to exercise discretion,” before storming out, slamming the door behind him.

The posh voice from Cabinet Office appeared on the phone again that afternoon, sounding gleeful. “Oh, very well done. You should probably back down now before you give him an aneurism.”

While all this was happening inside, outside a band of spies pretending to be terrorists hijacked a school bus filled with soldiers wearing t-shirts that said CHILD on the front, and disappeared in the Welsh hills as police and agents hunted fruitlessly.

The lessons from every one of these staged games were enormous. This was why everyone was there. To train the police about wind directions and chemicals. To understand how attackers might react when under fire, and where they might hide. To practice communicating to the public in order to keep everyone calm and safe.

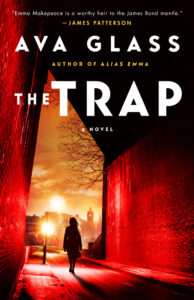

When I sat down to write The Trap, all of this was in my mind. The meetings in unmarked buildings, the long weekends in the middle of nowhere, the endless training and preparation for every event – all of it plays into the lives of my fictional spies.

There wasn’t a single tuxedo in sight in all those years. Not the slightest hint of Daniel Craig. But there was excitement and danger and risk. And so many lies. A mountain of lies.

Because of that, when people ask me if my books are realistic, I can honestly say: Probably not. But… maybe.

***