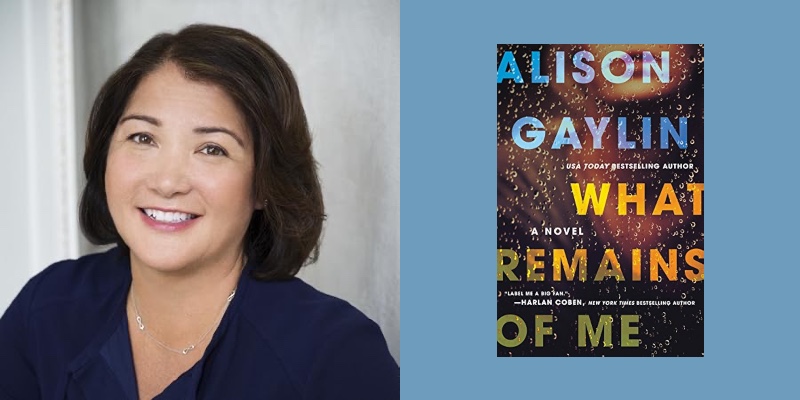

I have high standards for vacation reads. I’ve never been one of those people who saw a trip to the beach as an excuse to read something that only required half my attention. Even if I’m reading on a plane or by the pool, I need a smart, well-written page-turner, and a couple of years ago, I realized that I could never go wrong with a novel by Alafair Burke. The New York Times-bestselling author of twenty novels, including two series and many standalones, she manages to combine characters I’m eager to learn more about with tightly-woven plots full of breathless twists. (Her latest, The Note, kept me up hours past my bedtime.) In this interview, she introduces me to another author I’ll be following from now on, Alison Gaylin.

Why did you choose What Remains of Me by Alison Gaylin?

I love Alison Gaylin’s work, and this is one of my favorite books of hers. I love a two-timeline mystery, where things that you thought were going to stay in the past creep into the present. And it’s a very complex and layered plot, with lots and lots of twists, and I think she handles it really masterfully.

The main character is Kelly Lund, whom we meet in both timelines. In the first, she’s a teenager rebelling against her parents; in the second, she’s a convicted murderer who has recently been released after many years in prison. Part of what’s interesting about Kelly is how unremarkable she is: unlike her twin sister Catherine (who dies before the novel begins), she doesn’t have much interest in being a movie star. What do you think makes Kelly a compelling character?

We know about the murder from the beginning, so Kelly has this mystery about her from the opening pages. Then you see her in the present as an adult, after she’s released from prison. She’s trying to live a normal life with her husband, but then she gets pulled back into the orbit of these Hollywood figures that she’d tried to leave in the past. That was one of my favorite parts of this book, this atmosphere of the Hollywood elite and these details about how their world works that I don’t think most of us are privy to.

In the later timeline, Kelly is married to Shane Marshall, the son of a famous actor and the brother of Kelly’s best friend/arch-nemesis, Bellamy Marshall. Why and how is the Marshall family important to Kelly’s story?

We learn early on that Kelly’s mother is very anti-Hollywood. She worked as a makeup artist, and Kelly’s father, who’s out of the picture, was a stuntman, so they were very much on the periphery of that world. When Kelly becomes friendly with the Marshalls, and eventually marries one of them, that family represents everything that was aspirational but also repellent. There’s something obviously appealing about glitz and glamor and fame, but the distrust of it was also ingrained in Kelly by her mother. It’s scary to her, but also kind of irresistible.

Kelly was convicted of killing the director John McFadden, the father of one of her best friends. John is described as an auteur who is completely absorbed by his work, but there seems to be some kind of commentary about being so obsessed with making art that you don’t have time to care about other people. In a way, it’s an uncomfortable idea for writers– that caring too much about your work might give you an excuse to be a bad person. Is that how you read McFadden’s character, and do you think this is a risk for artists in real life?

I think that’s a character that many of us recognize, right? Their talent or their commitment to their artistry can sometimes provide a cover or an excuse for some pretty inexcusable things. Like everyone will say, “Oh, he’s so brilliant, you can’t expect decent behavior from him.” We all like to think we’re dedicated to our work, and absorbed in our work, but if it takes away from your moral sense, that becomes a problem. And if there are enough of those people, you have a world where the usual rules just don’t seem to apply. When the Weinstein story came out, and then the floodgates opened, it became very clear that there were people in this industry getting away with horrendous behavior. We know now that it was an open secret and nobody complained, because the mindset seemed to be, “Well, this is Hollywood, so different rules apply.” It’s such a fantastic setting for a mystery, because the potential witnesses and the potential complainants may also have slightly skewed views of right and wrong. So the consequences of speaking up might be very different than they would be if you set that story in Kansas.

I feel like I’ve been reading a lot of novels set in L.A. lately, and of course there have always been so many great crime writers there, from Raymond Chandler on. Is there some specific quality to L.A. crime novels that is unique to that setting?

I’ve been setting novels in East Hampton recently, and it seems to me like a smaller version of the same phenomenon. Even if you’ve never been to the Hamptons, or to L.A., you feel like you know it. The reader knows what it stands for, and you can take advantage of that as a fiction writer. To the reader, it’s fun to feel like you’re getting a little glimpse behind the scenes, like you get to see what the parties are really like. Then Alison is able to expose the seamy underside—the paparazzi everywhere, and the kids who have been corrupted by their access to resources and to fame. And then to take an insecure girl like Kelly and drop her into that makes for a really good story.

There are multiple twists and reveals in this story, and without giving any spoilers, I thought Gaylin handled them so well. What did you think?

Alison is one of my good friends, and we talk a lot about process. I think our books read similarly. I’m not sure exactly how to explain that, but there’s kind of a humorous tone to them. There’s a lot of pop culture in there, and we like a multi-layered reveal, with lots of plot twists. Constructing a plot like that is almost like a little brain teaser. You’ve got to work out how you’re going to time all of those reveals. I haven’t talked to her specifically about how she constructed this novel, but because we’ve talked a lot generally about craft, I know that she’s always asking herself, “How can I twist this one more time? How can I put in one more thing that the reader won’t see coming?” And I think it pays off so well in this book.

That suggests to me that she’s trying to surprise herself as well as the reader, right? Is that something you’re trying to do in your own work as well?

I’m in the process of beating out my various plot reveals for the next book now, and sometimes I have to wonder, “Have I thought about it too much? Like, is it one too many turns of the Rubik’s cube?” But in the end, it’s really about the motivation, and about the characterization behind those motives. If you just take a plot and strip it down to its bones, and you don’t explain the dynamics behind the characters’ decisions, it’s not that interesting. But when you understand the reasons why people are doing what they’re doing, and the way it’s all interrelated, that’s the beauty of it.

I always think about that line how Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did, and she did it backwards in high heels. Great crime writers do all the things that literary writers do, but with a plot that keeps readers turning pages.

Yeah, things have to actually happen. People who don’t read a lot of mysteries might think that they all follow a standard linear plot line, where somebody finds a body and then a detective comes and starts interviewing people, but Alison is doing something much more complex than that. You’ll be reading a scene about Kelly in high school, and you’ll hear a stray detail that you won’t realize was significant until much later. I think the structure of this book is so clever. In some mysteries I read, there will be a this really clunky dump of exposition—like someone will be folding laundry, and then they’ll remember something for three pages. In this novel, the scenes unfold seamlessly, and yet they contain so much information.

I’m so glad you suggested this title. I’ve always meant to read Gaylin’s The Collective, but now I want to go back and binge everything she’s written.

The Collective is amazing. The title refers to this group of people who have had horrible things happen to them and their family and never got justice, and they find each other and start working together. I think she wrote that during a time when we were all becoming aware of the collective anger among women about people getting away with bad behavior and never facing consequences. Her most recent book, We Are Watching You, has kind of a similar set-up to What Remains of Me, where the main character has something happen to her as a child that affects her current life, and she ends up as a target of this group of online conspiracy theorists. It’s very scary and creepy because it shows the allure and the danger of these online groups. It’s very timely.

Is there anything else you’ve learned from this novel that you might apply in your own work?

Rereading this book reminded me that you really can’t detach character from plot, and also that experimentations with structure can pay off. It’s not just the switches of point of view—she includes chapters of a true-crime book written by one of the characters, and news articles. It reminds me that a reader will go along with you with those experiments if you do them well.

It’s so intricate. I would love to see what her plot board looks like.

Laura Lippman does that really well too, and I think she’s even posted pictures of, like, different-colored Post It notes in lines on the floor. I’m a whiteboard person and an index card person myself, but right now, my board is pretty empty.

Are the early stages a fun part of the process for you?

No, it’s horrible. I have a very hard time starting because I’m always convinced I don’t know enough. And I had to literally write a note to myself yesterday saying, You knew less than this when you started The Wife. I have to remind myself that sometimes it helps if you don’t know too much going in, because your characters don’t know too much either. Most of the writers I know say that it always feels the same way—like, “How did I ever do this?” But Harlan Coben always says it’s easier to fix it than it is to write it the first time. You can always make it better.