In Anthony Doerr’s great essay “The Sword of Damocles: On Suspense, Shower Murders, and Shooting People on the Beach,” he unpacks the etymology of the word “suspense”: “Its origin comes from the Latin suspendere, and inside of suspendere is the word pendere, which means to hang.” Etymologically speaking, “suspense” seems to imply slowing down the rate of revelation by forcing the reader to hang suspended in time, existing in a prolonged present moment. But how do you do that without running the risk of boring or frustrating your reader?

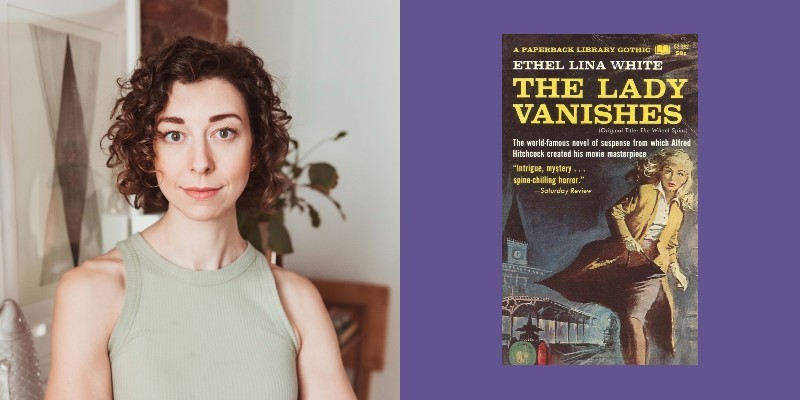

Andrea Bartz has thought deeply about these questions of craft. She is the author of The Lost Night, The Herd, We Were Never Here, a Reese’s Book Club pick and instant New York Times bestseller, and this summer’s forthcoming The Spare Room, (out June 20th). I was thrilled when she chose to talk about The Lady Vanishes, a 1936 novel by British mystery writer Ethel Lina White that I’d heard of but had never read. In our interview below, we talk about how to keep a reader hanging, the difference between a twist and a reveal, and why a train may be the perfect metaphor for suspense.

How were you first introduced to The Lady Vanishes?

Well, I first read it when I was thirteen or fourteen, and then pretty much forgot about it. Then I recently read Lucy Foley’s The Paris Apartment, and in the back of this particular edition, they had a section on the books and movies that inspired the novel, and one of them was The Lady Vanishes. Foley said it was an inspiration in terms of writing about a character who feels like a fish out of water in a country where she can’t speak the language, and just how isolating and terrifying that could be. I knew I’d read it decades ago, but I didn’t remember much about it, so rereading was kind of like discovering it for the first time.

How did you come to read it when you were a teenager?

There was a library within walking distance from high school, so I went there a lot. Even before that, my mom would take my sister and me to the library every single week. I went through phases—I had my Goosebumps phase, and my R.L. Stine’s Fear Street phase. And there was a time where I was really into Agatha Christie, and I was just picking up every dog-eared paperback of Agatha Christie that they had. I remember seeing somewhere that if I liked Agatha Christie, I would like The Lady Vanishes, so I checked it out on a whim along with a whole bunch of other books. I remember really liking it, but I couldn’t tell you why. I just remember thinking it felt sort of glamorous, and I remember loving the setting. But at the time, it was part of one long string of books in that genre that I was reading back then.

How was your experience different when you reread it as a suspense writer?

From the very first page, I was really impressed with the quality of the writing. Sometimes you return to stuff that you loved when you were younger, and it really doesn’t hold up. But I thought the writing in this novel struck a really nice balance between a plot that kept things moving along and this borderline-flowery, very beautiful prose. There was a lot of figurative language that I was highlighting because I thought was beautifully written. She’s good when she’s describing something external, but she also does an incredible job putting words to internal sensations. I think she’s such an incredible writer when it comes to the lived experience and making it feel relatable. I had this very fun feeling of envy and admiration and inspiration that you get when you encounter something really well-written.

I also thought the story really clicked together. I’m impressed with the fact that not that much happens compared to modern-day thrillers. We’re not starting with bloodshed and red herrings and all that, and yet you can’t look away. It’s so compelling, it moves so quickly. An incredible amount of skill went into making that look effortless.

I know what you mean. She’s willing to take her time getting to big plot points, and it’s really luxurious.

Yeah, it just feels so indulgent. And I love it.

Have you ever gone back and read any of her other work?

No, I haven’t. I will now, because I’ve learned that if you enjoy a book by someone, you should go read their backlist—like, run to it. At the time, it was a one-off until more Agatha Christie books were back on the library shelves, but I do want to go back now and read some of her other fiction, because I find this book both wildly entertaining and fairly educational for myself as a suspense writer.

How so?

The novel centers around Iris’s search for Miss Froy, which is hampered by her fellow passengers’ assumption that she’s not thinking clearly. So much of the fun of the book is that knife edge of, “Who’s lying here?” Is Iris deluding herself or imagining things, or is everyone else conspiring against her? It’s fascinating how we, as readers, are brought into the minds of so many other characters. It’s so seamlessly and expertly done. It’s much rarer these days in suspense to have omniscient narration. A lot of the psychological thrillers I read are in first person, and when they’re not, they’re in a very close third. In this novel, even before Iris gets on the train, the point of view is flitting between different people; even before the mystery is set in motion, we get to experience the same moment from several different people’s perspectives.

There’s this one tiny moment near the beginning where Iris has gotten lost on a hike and finally gets back to the hotel, and she’s like, “Please don’t let anyone speak to me.” And then we flip over to the mind of somebody else at the hotel, who looks over like, “I really don’t want to talk to that girl, but I’m going to take pity on her and go over and say hi.” There’s so much delicious irony in that narration, and then White makes great use of it in the mystery when we get crucial pieces of information from other characters that begin to fill in our understanding of what’s really going on. I have so much admiration for how she made all these characters feel real and engaging, with really distinct personalities and distinct voices, even in third person. You understand why everyone is doing what they’re doing, whether you agree with them or not.

I was just thinking a contemporary editor would probably want you to do alternating chapters, where there’s one from Iris’s point of view, and then the next from somebody else’s. And I love the freedom of omniscient narration and how it lets you arrange information in the way that makes most sense for the narrative.

Absolutely. I haven’t written a book with an omniscient narrator, but my second novel, The Herd, had alternating narrators. There were definitely times when I was like, Man, I want to stick with this person for two chapters in a row. And you’re right, the omniscient narration here allows White to arrange information in a way she wouldn’t be able to otherwise. There’s this great moment where Iris asks a waiter to bring her soup and he nods, but then she never gets it. Then later we learn through his perspective that he doesn’t understand English and had no idea what she was saying. He’s not an important character and it has no real bearing on the plot, and yet we get just enough of his story for him to feel like a real character. I have so much admiration for the fact that for every single character, major and minor, White creates a full image of them in your mind.

That part with the soup stood out to me too. We’re assuming by that point that everyone’s involved in this conspiracy against Iris, so I was thinking, “Oh, the waiter didn’t put in her order because he’s part of it.” Then when you realize that’s not his motivation at all, it’s just such a great moment.

Exactly. When you actually find out the reasons why people aren’t helping her, it’s not always because they’re covering anything up, it’s because they have their own private motives that she doesn’t understand. That feels very realistic to me. Meanwhile, Iris has this paranoia around what she perceives as this growing collusion and conspiracy against her. It plays with the reader’s expectations as we try to figure out what is Iris’s paranoia versus actual bad things coming her way.

How fun that must have been for the author. There are so many novels now where people are unreliable because they’re drunk, or something is causing them to think in a disordered way. But Iris is just kind of selfish and wants to interpret everyone’s actions based on what she wants, rather than acknowledging that other people might have different wants. So it’s basic human nature that’s causing her to misinterpret everybody.

To be fair, some of them are intentionally gaslighting her. There’s this great line I highlighted where the mistrust has gotten to her and she thinks, “Perhaps, after all, I’m not reliable.” And I thought, oh man, we’ve got our original female unreliable narrator here. Iris walked so Amy Dunne could run.

I won’t include any spoilers, but this novel has an iconic twist—so famous that I realized halfway through that I knew what was going to happen even though I’d never seen the movie or read the book. Do you have any thoughts on what makes it so famous and how White pulls it off?

It’s great. It’s a very fun sort of twist slash solution slash reveal. I knew it was coming too since I’d read the book before, but it didn’t diminish my enjoyment. For me, even if I know a big moment is coming, I still love seeing how we get there. I love admiring how they did it. I mean, as readers, we’re constantly making guesses about what the solution might be, right? That’s what makes it fun to read a thriller or crime fiction, we’re making all these guesses. You’re holding a small handful of different possibilities, different solutions in your head at the same time. And then when you find out which one it actually is, it feels inevitable, because it was properly seeded from the beginning.

How do you define a twist, as opposed to a reveal?

For me, a twist is something that takes the story in a totally new direction and makes you rethink everything that came before. You realize that everything you thought was wrong. A reveal, on the other hand, isn’t actually undoing anything, it’s just a piece of information that the director or author has been holding back, and now they’re going to give you. A lot of what we experience as a plot is just increasing levels of access to new pieces of information. Once we have them, we can integrate them into our understanding. But a real twist is when you have to go back to the beginning and realize that everything you’ve been thinking is completely wrong. There’s the classic twist in Gone Girl, for instance, but there are also plenty of reveals that come earlier. Like, we didn’t know at the beginning that Nick had a young, hot side piece, and now we do.

The villains of the novel are all Eastern European, and often characterized as brutal, authoritarian, unethical, and deceitful. It reminded me of reading old Nancy Drews when I was a kid, where the villains were always swarthy. How do you think we, as modern readers, we should process this element of White’s work?

It’s striking to me that those stereotypical portrayals have very little to do with race, at least as we understand it now. A lot of people that we now would consider White were considered people of color and maligned in those terms. That’s certainly going to be unacceptable to modern readers, insofar as we can credit those negative portrayals to the author. But there’s also an element here where those negative reactions are coming from Iris’s consciousness, and they’re connected to the fact that she can’t speak the language. She’s realizing just how isolating that is, and becoming frustrated with herself and with them because she’s unable to communicate with them. And that is definitely something I’ve experienced, because I used to travel by myself a lot. In 2019, I was doing this big, multi-week, multi-country solo trip around Central Europe, and on the third night, someone stole my wallet out of my bag in Budapest. I got the bill at the end of a meal and I wasn’t able to explain to the waitstaff that someone took my wallet and I needed to talk to the police. I was so frustrated, and it probably seemed like it was coming out as frustration with them. I might be giving the author too much credit, but I do feel a part of that characterization of the people around Iris as cold and unhelpful is filtered through her frustration.

Have you learned anything from this novel that you’d apply to your own work?

One of the things that stood out to me was how she sprinkled in elements from other genres. There’s a lot of humor. There were a couple conversations between Iris and the guy she meets where they’re cracking up, and White really captures that flirty, witty back-and-forth. There’s a little bit of romance building at the end. I appreciated how she played with tone without ever letting her foot off the gas. She keeps up the drumbeat of suspense, but we still have these moments to breathe, we have these moments where you get to collect your thoughts. Sometimes we leave the train altogether and hear about some other characters doing something else, and yet it never feels like it’s taking away from the driving question. I want to be cognizant of using that in my stories where, without stepping so far away, you take the narrative in another direction for a little bit. You give the reader a brief respite and then when we do get back into the action, it feels even more intense.

I also thought the train was a great metaphor, with the intensity and the suspense and the speed and the racing over the tracks. The engine is getting louder and louder just as Iris realizes she needs to figure this out by the time they reach a certain station where people will go in different directions. That ticking clock is such a great way to amp up the pressure. I also loved how she used the claustrophobic and closed setting of the train to enhance the sense of terror for the main character and for the reader. That’s something I want to be cognizant of too, playing with both literal and metaphoric space.