When I first learned that “Liv Constantine” was the co-writing name of two sisters, Lynne Constantine and Valerie Rees, I was immediately fascinated. How did they do it, I wondered? We tend to think of the writing process as a necessarily solitary activity, so how could you share that task with someone else? Would it be fun or frustrating, productive or tedious to collaborate with another writer, especially a family member? I couldn’t wait to talk to them about it, and when I saw that their new novel, The Senator’s Wife, was out this spring, I jumped at the chance.

I read The Senator’s Wife in one sitting. I’ve always been fascinated by the private lives of D.C. power brokers, and Constantine provides a compelling window into that world. The main character, Sloane, is struggling with lupus and with the death of her congressman husband when she’s surprised to find herself falling in love with his best friend. After her remarriage, her condition deteriorates, and she and her new husband hire a home health aide to help care for her. What follows is a twisty, addictive ride that kept me guessing the whole time.

This month I got to talk to the Constantine sisters about a short story from one of the masters of British detective fiction, Dorothy Sayers. As novelists working in a different tradition, they still find a lot to admire and learn in Sayers’s suspenseful, plot-driven tale, where a man named Pender meets a stranger who tells him he’s figured out a way to commit the perfect murder.

Why did you choose Dorothy Sayers’s “The Man Who Knew How”?

Lynne: I just really love it. The close point of view sucks me in. You’re getting all these details about the stranger, and Pender, the point of view character, is watching him so closely that he begins to seem kind of weird and paranoid. It’s such an interesting situation, and so beautifully written, and right away you know there’s more to it than met the eye.

Do either of you write short stories?

Lynne: We’ve written two short stories together—not quite this short, more novella-length. And then I just recently finished an Amazon short, which was only 10,000 words. You’d think it would be easier than writing a novel, but I actually found it very challenging, because you don’t have a lot of time to get the whole story arc in there. As a novelist, I’m so used to wanting to provide all this backstory and really flesh out the characters, and you don’t have a lot of space to do that in a short story.

Did your process change at all in writing a short story together?

Valerie: We had to structure them differently, because we were dealing with shorter periods of time and just one incident. But as Lynne said, they weren’t as short as this. This was really this was just a few pages. Sayers had to cram a lot into that space, and she does it extremely skillfully.

“The Man Who Knew How” is reliant on plot to the extent that we know almost nothing about the main character. Do you have any thoughts on why she chose to do that?

Lynne: Well, if you don’t know too much about him, you don’t know how reliable or unreliable his perceptions are. You have to put yourself in his shoes, and maybe it’s easier when you don’t know a lot about the person.

Valerie: That’s a good observation. It’s almost like you become the point of view character. If you knew that he was a bad person or that he was hiding something, it would be a totally different experience.

Have you read a lot of British crime fiction? How would you compare it to the American version?

Valerie: I love Ruth Rendell and P.D. James, and I think I’ve read everything Agatha Christie ever wrote. In terms of the comparison, this story was published in 1932, and if we stay in that timeframe, we’re comparing Sayers to writers like Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler, which immediately brings to mind this detective who’s hard-boiled and hard-drinking, and they have all this baggage, and their lives are a wreck. Whereas in British detective fiction, you have somebody like Hercules Poirot, who has the little gray cells and solves the crime through his intellect. Or sometimes the sleuth is an amateur detective, rather than somebody who’s a real P.I. Then in American detective fiction, there are usually lots of corpses and bullets and car chases and violence, whereas in the British ones, there’s often only one murder, and it’s done quietly. I think those are the big differences between the two.

I can understand why you’re drawn to British crime fiction when I think about your work. It seems like you’re most interested in the intellectual process and the manipulation behind a crime.

Valerie: Yes, we’re definitely interested in the psychological aspect. What makes characters tick? What motivates them?

Lynne: Sometimes we get to a certain point and we have to ask each other, would this character really do that? What’s the motivation? The emphasis is on characterization rather than a high body count.

For my last interview for The Backlist, I talked to Andrea Bartz about Ethel Lina White’s The Lady Vanishes, which was written around the same time and also takes place on a train. Why do you think trains are so appealing as a setting?

Lynne: First of all, it’s the confinement. You’re in this moving box, in a confined space, and if you strike up a conversation, it feels very intimate because no one else is around. Until the train stops, you don’t really know where the other person is going, so there’s that element of mystery. And it does seem to engender the desire to share secrets. I think we’ve all had that experience, where you just start chatting with someone beside you, but who knows who you’re really speaking to. You could be striking up a conversation with a killer, or maybe you’re meeting somebody who could become a friend. Then there’s an elegance to the older stories with the train. Maybe you’re in first class, and you have cocktails. It’s a very appealing setting.

We wouldn’t call Pender an unreliable narrator since the narrative is in third person, but he is, in a sense, an unreliable character. We’re in his thoughts for most of the story, and he makes a lot of assumptions. Without giving any spoilers, why do you think Sayers chose to keep the reader inside his perspective?

Lynne: I think thrillers and mysteries have always played with point of view and with the reader’s access to knowledge. The trick is to do it in a fresh way that makes sense. Here, I thought it really worked, because I understood where Pender was coming from.

The man on the train tells Pender that he’s developed a method for committing the perfect murder. Do you have any thoughts on why the perfect murder is attractive as a trope?

Valerie: Probably there are a lot of us who have tried to concoct the perfect murder, not because we want to go out and commit it, but because it is this age-old riddle. Could you really get away with murder, and how would you do it? Today, with technology and cameras everywhere, it would be even harder, but it’s a mental puzzle that people love to think about.

Is there anything else you learned from the story that you would use in your own work or that you think you’ll come back to?

Valerie: For me, it was Pender’s obsessiveness. As his obsession with the man on the train increases, so does the suspense and the tension.

Lynne: I would agree. I think too it’s interesting to be reminded that you don’t always have to provide lots of backstory, and that it can be just as effective to withhold certain things and let the reader figure it out for themselves.

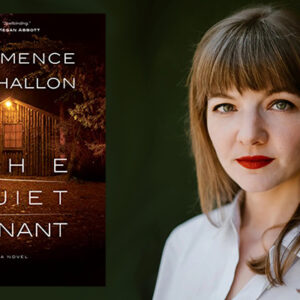

–Author photo by Bill Miles