Every writer likes to think they’re a psychologist. Inventing a character means having at least a cursory sense of their backstory, motivations, past traumas—the history that makes them unlike every other person in this world. By definition, writers are observers and people-watchers, and most of us believe that this gives us an uncommon understanding of what makes them tick.

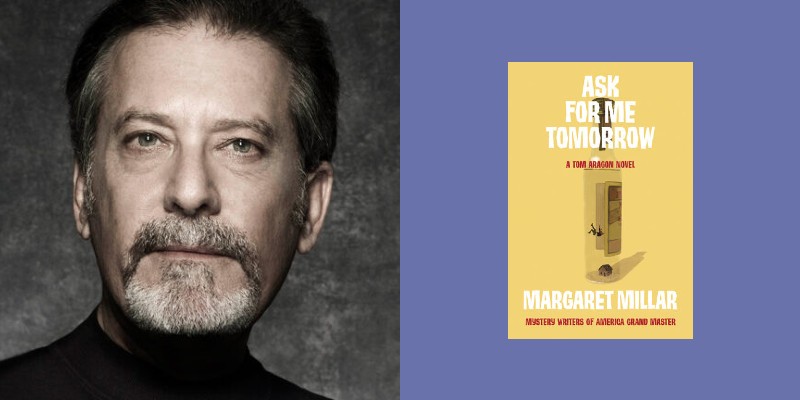

But Jonathan Kellerman really is a psychologist. Prior to his career as a novelist, he worked as a staff psychologist and clinical professor of pediatrics at the USC School of Medicine and then opened a private practice. He is now a clinical professor of pediatrics at the Keck School of Medicine, but he is better-known to the general public as the author of the Alex Delaware series, which spans thirty-nine novels published over thirty-eight years. Delaware is a forensic psychologist who often partners with LAPD detective Milo Sturgis. The latest installment in the series, The Ghost Orchid, was published in February. For this month’s column, I sat down with him to talk about another great Southern California crime writer, Margaret Millar.

Why did you choose Ask for Me Tomorrow by Margaret Millar?

Well, here’s the thing: I never read fiction while I’m writing fiction, and I’m almost always writing fiction. So in between books, I will treat myself to some good fiction, and I want it to be really great. We’ve got thousands and thousands of books in this house, many of which I bought decades ago in thrift shops and used bookstores during my starving graduate student days. I first got interested in Margaret Millar through her husband, Ross Macdonald, who was a big influence on me as a writer. When I was finding my voice, he helped give me a focus, and after I learned about him, I learned about her. I became especially fascinated by them because like my wife Faye Kellerman and me, they were a husband and wife writing fiction.

I’m not going to say books helped me or influenced me. I’ve been doing this for forty years. I don’t like to be distracted, even on a subconscious level. But I love this book, especially the darkness and mordant humor in it. It’s probably not a novel that could be published today because it’s not politically correct, but it’s all the better for that. The old cliché is that you have to have likeable characters, but Millar didn’t have a lot of likeable characters. She had a very dark view of the world. She and her husband were both alcoholics, and they had a very tortured marriage. In her pictures, she looks like a nice matron from Santa Barbara, but she was producing these amazingly dark stories.

I was glad to get the chance to read Millar, because I knew Macdonald’s work but not hers. I love Sue Grafton, and that’s how I got to Macdonald, because he was such an influence on her.

I knew Sue very well. We broke in around the same time, and one time we found ourselves doing a joint signing at a mystery bookstore here in the Valley. Nobody showed up, so we were just sitting there getting to know each other, as happens a lot. Sue had copies of A Is for Alibi, so we bought one, which later turned out to be a collector’s item. Sue was just lovely, really smart and extremely witty and a lot of fun.

We were both big fans of Ross Macdonald—I think he’s the greatest. I know a lot of people like Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, and I think they’re talented, but I think Macdonald is just way superior. He really helped give me a voice. I’d been writing since the age of nine, but I didn’t know what I wanted to write. I wrote comedy or satire or nonfiction, and I wrote medical stuff. Then, when I was working at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, I was on my way to work, and I saw a book shop with a sign on the window saying Going Out of Business. I went in and I bought Ross Macdonald’s The Underground Man for fifteen cents, and that really pointed me in the direction of where I wanted to go. I felt that what I did as a psychologist was detective work, basically, and I had quite a lot of experience with the criminal justice system. The rest is history.

One of my favorite parts of the novel was the setting. I’ve never been to Baja, but I imagine it’s no longer much like the sparsely populated, lawless wasteland described by Millar.

That was before my time, of course. When I was a kid, we’d go down to Tijuana, and it was just known as a place where you bought tacky stuff. Then later I had some friends who wanted to go down and engage with the hookers. I begged off; it wasn’t my thing. There were strip clubs and live sex shows back then, and now it’s dominated by the cartel, so I don’t go there a lot.

Most of the writers we’ve been talking about lived and wrote in Southern California. What do you think is significant about that landscape for crime writers? How do they manage to instill so much darkness into that sunny landscape?

I think the greatest American crime novels have been written in Southern California, in L.A. and Santa Barbara, or Santa Teresa as Macdonald and Grafton called it. I’ve always wondered why New York doesn’t produce the same kind of great crime fiction, the exception of course being the Matt Scudder series by Lawrence Block. The only thing I can think of is that L.A. has these extreme differences between the haves and the have nots that create tension. Warm weather helps too, because even bad guys don’t come out when the weather’s really terrible.

When my family first moved to L.A., it was more of a conventional city, but now it’s utterly and totally dominated by the film business, which is a business that traffics in illusion. It traffics in falsehood, and until recently, it trafficked in a lot of immorality. I knew Elmore Leonard quite well, and I always think about his book Get Shorty, about this guy Chili who’s a bone breaker for the mob in Florida. He’s a terrible guy, he beats people up for a living, but then he comes to L.A. and gets involved with the film business and is appalled by the immoral people he meets. I always thought that was Dutch getting back at the industry.

You still see people coming here because they’ve run out of places to go. When I was a psychologist, I’d take a family history before I treated a child, and it was amazing to me how many people who settled in L.A. had no relatives there, no connections. It’s a place that tends to cater to disjointed people, and that’s great fodder for a crime novel. The greatest hardboiled novels have taken place in southern California and I’m happy to be part of that.

Do you know much about the working relationship between Ross Macdonald and Margaret Millar? Did they ever collaborate?

I don’t think they ever collaborated. I’ve spoken to people who knew them personally, and I don’t think they had a happy marriage. They were both heavy drinkers, and that probably didn’t help. Ross Macdonald was a very quiet man, from everything I’ve heard. The musician Warren Zevon, who was a very close friend of mine, knew Ross Macdonald, and he said the thing with Ross was he just wouldn’t talk. You had to get used to long stretches of silence.

Faye and I have collaborated on a couple of novellas, and it was wonderful, but we decided we didn’t want to do it again. We’ve been together for fifty-three years, and we have four kids and a dozen grandkids. When you’re raising four kids, you have no privacy, so the only privacy we ever had was coming into our separate offices and writing. And there was a desire to keep that, even though we love being together.

When I started out, it took me a long time to get published as a novelist. I finally broke in, and since then every book has been a bestseller for forty years, but it definitely didn’t happen overnight. Faye had a degree in theoretical mathematics and a doctorate in dentistry, and I never saw her as the literary type, even though I knew she had a great imagination. Then unbeknownst to me, she started writing. One day I was holding our third kid, and Faye came up and handed me a sheaf of papers and said, “Here, read this, you’re going to hate it.” But then I read it and it was really good. I called my agent and said, “I know what this sounds like, but my wife wrote a book.” He said later that his eyes were rolling back in his head, but he loved it and she got published right away.

In the beginning, we would show each other what we’d written every week, and it led to some cold nights. I wanted to be tactful, but sometimes it was hard. Then we stretched it out to once a month, and then after several novels, we basically didn’t show each other anything until the book was finished, and that’s how we’ve been doing it ever since. We don’t ever talk about the craft of writing, but we talk about the business of writing. People used to ask our kids in interviews, “What’s it like growing up with two bestselling authors as parents?” and our son would always say, “It’s not like that.” We were a regular family, very child-oriented, and we talked about the same things all families talked about. I think I owe my wife that because she she’s just the least presumptuous, pretentious person you’re ever going to meet. She just doesn’t take it that seriously.