In the early 1930s, James Joyce’s Ulysses was the most notorious banned book in the United States. Using a stream-of-consciousness style to describe twenty-four hours in the life of a lower-middle class Dubliner named Leopold Bloom, Joyce’s classic, published in 1922, was brilliant, dense, convoluted, complex, and legally obscene. Ulysses was the “only volume of literary importance still under a ban” in the country, Morris Ernst declared. He set out to “liberate” it, and the celebrated case, resolved by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in 1934, was not only a landmark in the law of literary censorship but also a turning point in Ernst’s career.

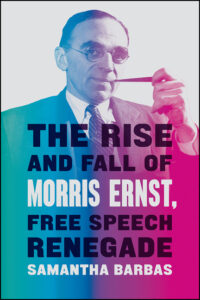

(Featured image: Ernst defends Flaubert’s November in 1935.)

***

Joyce’s novel had a long history of suppression in the United States. Ulysses had been banned even before Joyce finished writing it. In 1918, as he was completing Ulysses, Joyce sent chapters to the New York–based literary magazine the Little Review, which published them in installments. The Post Office Department confiscated the issues and burned them. Shortly after, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice had obscenity charges brought against the Review’s editors for having published the chapter in which Bloom masturbates while watching a young woman on the beach. John Quinn, a noted literary lawyer and patron of the arts, defended the editors in court. Despite Quinn’s persuasive argument—Ulysses was so dense and convoluted that no one could possibly understand it, much less be debauched by it, he argued—a three-judge panel, using the Hicklin test, concluded that the book had the potential to corrupt youth and was therefore obscene. After the New York decision, no American publisher was willing to take a chance on Ulysses. The book was eventually issued in Paris in 1922, under the imprint of the avant-garde bookstore Shakespeare and Company. Joyce gave Sylvia Beach, the bookstore’s proprietor, the world rights to Ulysses.

The ban on the book notwithstanding, Ulysses found a wide and receptive audience in the United States. Blue paperbound copies were smuggled into the country and sold at fantastic prices, sometimes as much as fifty dollars. Joyce won critical acclaim for Ulysses; articles and treatises were written about it, its style was widely imitated, and the book achieved masterpiece status. Observed critic Harry Hansen in 1933, a generation of Americans coming of age in the 1920s grew up “with the idea that [Ulysses] is a literary Bible.”

Because Ulysses could not be legally published in the United States, it could not be copyrighted. Samuel Roth, an infamous publisher of pornography, seized on this opportunity and began to publish bowdlerized installments of Ulysses in his magazine Two Worlds Monthly. Joyce sued Roth over the unconsented use of his name. One hundred sixty-seven of Joyce’s literary friends, including T. S. Eliot, D. H. Lawrence, and Thomas Mann, signed a petition protesting the “appropriation and mutilation” of Joyce’s work. Joyce won an injunction in 1927. Meanwhile, US Customs officials seized copies of the book that were imported from Paris. In 1928, the US Customs Court, in an action titled A. Heymoolen v. United States, affirmed the exclusion of Ulysses as an obscene book.

Joyce, who was living in Paris, launched a search for a reputable American publisher. Aging, syphilitic, and nearly blind, he was desperate for money, and it was rumored that Roth was going to sell another pirated edition, publishing as many as twenty thousand copies. A few US publishers, sensitive to the changing cultural climate around sex and the more liberal obscenity rulings in the New York courts, began to discuss the possibility of bringing out an American edition of Ulysses. But no one was willing to commit to it; with the legal restrictions in place, publishing Ulysses was a still a risky proposition. Ernst knew about the renewed interest in Ulysses, and in the summer of 1931 he had asked Alexander Lindey to help him find a publisher that might be willing to publish the book and cooperate in a test case to remove the ban. Ernst planned to deploy the same strategy he had used in the Contraception and Married Love cases—he would have a copy of Ulysses imported from France and seized by the Customs Office under the Tariff Act as an obscene book, and then he would challenge the seizure.

Joyce and Beach, in Paris.

Joyce and Beach, in Paris.

In August, Lindey had a lengthy conversation with Sylvia Beach’s sister, Holly Beach Denis, about the possibility of an American publisher obtaining the rights and participating in the “legalization of Ulysses.” Denis said that she was “tremendously interested” and that Sylvia Beach would likely cooperate if a suitable publisher could be found. Shortly after, Lindey wrote to Ernst, “I . . . feel very keenly that this would be the grandest obscenity case in the history of law and literature, and I am ready to do anything in the world to get it started. What do you suggest?”

“Tell Mrs. Denis that I want to see her,” Ernst replied. “I am sure I can get a good publisher.”

Two months later, Ernst lunched with Ben Huebsch, ACLU member and vice president of Viking Press. Viking had published Ernst’s To The Pure, as well as Joyce’s Dubliners and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. In a letter after the lunch, Ernst told Huebsch he was confident that because of his recent victories in obscenity cases, Ulysses can “now be tested (in court) with the real hope of gaining immunity for it.” Ernst assured Huebsch that he had little to lose under his plan. Because customs actions proceeded against the book, rather than its publisher or mailer, no one risked fines or jail sentences. Huebsch didn’t have to spend a dime on publishing Ulysses until the court approved it—the fight would be waged over an imported copy of the Shakespeare and Company edition. Success in the customs case didn’t mean that it was completely safe to publish Ulysses, however, Ernst warned. The book could still be seized by the post office, and the publisher could be charged under state obscenity laws. The approval of Ulysses by a federal tribunal, however, made subsequent actions against the book “highly improbable,” according to Ernst.

As an incentive to get Viking to publish Ulysses and sponsor the case, Ernst offered Huebsch his usual deal. His normal fee was a retainer of $1,000. If the case were appealed to the Supreme Court, fees and costs could run as high as $8,000. Ernst proposed a contingency arrangement in which he would be paid a retainer of $500 and an additional $500 for each subsequent appeal. The maximum would be $2,000 if the case went all the way to the Supreme Court. In exchange for the reduced rate, Ernst wanted 4 percent of the book’s royalties.

Ernst knew he had a good chance of winning the case and that the publicity around the litigation would drive up the book’s sales. Huebsch agreed and approached Sylvia Beach about obtaining the American rights to Ulysses. When she demanded $25,000, Huebsch balked. Huebsch then wrote to Bennett Cerf, the young president of Random House, who had also expressed interest in publishing Ulysses. Huebsch told Cerf that it was fine for him to try to acquire the rights from Beach. Around the same time, Robert Kastor, a New York stockbroker who was the brother-in-law of Joyce’s son, approached Cerf and asked if Random House was interested in publishing Ulysses.

Cerf was thrilled at the possibility of issuing the first legal edition of Ulysses. It would bring Random House, then a fledgling company (only six years old), into major prominence in the publishing world. Cerf and Ernst met in March 1932, and Ernst offered him the same contingency deal he had presented to Huebsch. Meanwhile, under pressure from Joyce, Sylvia Beach agreed to give Joyce the world rights to Ulysses. By the end of the month, Random House had worked out a contract with Joyce in which Joyce received $1,500 and the firm obtained the US rights to the book. Ernst would litigate the customs case, and if the book were cleared, Random House would publish it. Under the final agreement with Random House, Ernst would receive 5 percent of the royalties if the book were legalized and published. Cerf “had not the faintest doubt” that Ernst would win the case. Ernst, he was sure, could handle the litigation “better than anyone else in the country.”

***

Ernst set the wheels of the “grandest obscenity case” in motion in 1932 when he instructed Cerf to have a copy of Ulysses sent from Paris to Random House’s office in New York. Cerf wrote to Joyce’s secretary Paul Leon asking him “to purchase the latest edition of Ulysses.” Knowing the courts’ resistance to hearing expert testimony in obscenity cases, Ernst had come up with the idea of pasting positive reviews of Ulysses into the book itself, which would be introduced as evidence. Cerf advised Leon, “if there has been printed . . . any circular containing opinions of prominent men or critics on this book, paste a copy of the circular into the front of the book. It is important that this circular be actually pasted into the book, as if it is separate we may not be able to use it as evidence when the trial comes up, but if these opinions of respected people are actually pasted in the book, they become, for legal purposes, a part of the book, and can be introduced as evidence.” Leon was told to notify Cerf what ship the book would be coming in on so that Cerf and Lindey could alert authorities. Cerf explained, “It is necessary that they catch this book or all our efforts in this matter will have been in vain.”

The main argument Ernst planned to make in court was by then a familiar one—that the question of whether a work was obscene should be determined by contemporary social standards, and it was “undisputed” that the public accepted Ulysses. Ernst planned to demonstrate this by showing the accolades the book had won from literary critics, professors, and other “prominent men” whose sentiments reflected public opinion. Ernst instructed Lindey to have Random House send more than five hundred letters to esteemed writers and intellectuals surveying their opinion on Ulysses. Cerf was also told to put together a massive file containing essays, articles, and positive reviews of Ulysses, as well as statements from “prominent critics, librarians, authors, physicians, psychologists, welfare workers, and the like,” attesting that Ulysses had major “literary, scientific, [and] sociological value.” Random House also sent a circular to one hundred colleges and universities, asking whether Joyce was used in courses. Nine hundred letters were sent to librarians, querying whether Ulysses was on their shelves or whether they would like to have it in their collections. By the end of May, Random House had received favorable responses from several important literary figures, including George Jean Nathan, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Hundreds of librarians said they wanted to have copies of the book and saw Ulysses as having major literary importance.

On April 27, 1932, Leon telegrammed Cerf that he had shipped a copy of Ulysses on the SS Bremen, scheduled to arrive in New York on May 3. Leon had pasted positive reviews into the book’s cover; he also sent several articles praising Ulysses that he hoped Ernst could use in his “speech before either the lower or the higher court.”31 Lindey alerted the collector of customs:

“A copy of James Joyce’s novel, entitled Ulysses, has been dispatched into this country, addressed to our client. We are informed that the volume left on the Bremen on April 28, and is due at the port of New York on Tuesday, May 3, 1932.

“We are transmitting this information to you because we do not wish the book to slip through the Customs without official scrutiny. As you may know, Ulysses during the last two decades has been praised by critics as probably the most important contribution to the world literature of the twentieth century. Entirely apart from its profound literary significance, we are convinced that Ulysses is not violative of the Tariff Act. In saying this we are not unmindful of the adverse attitude of your department with regard to the book in the past. We feel, however, that in view of such recent decisions as [the Dennett, Married Love, and Contraception cases] there is no longer any legal sanction for such attitude.”

A few days later the book showed up at Random House—it had passed through customs. Furious, Ernst personally marched the package over to the customs office and demanded that it be searched. When the inspector opened it and found Ulysses, he muttered, “Oh, for God’s sake, everybody brings that in. We don’t pay attention to it.” Ernst insisted that he seize it. On May 8, the book was officially seized by customs. Lindey urged customs officials to forward the book to the Offices of the United States Attorneys for proceedings. On May 24, 1932, Ulysses was sent to the US Attorney for the Southern District of New York for “forfeiture, confiscation, and destruction of the book in accordance with the provisions of Section 305a of the Tariff Act of 1930.” The battle over Ulysses had begun.

___________________________________