When my first noir short story was published, my mother-in-law held Orange County Noir, with the cover of a knife stabbing an orange, and said, “What is noir?” She read mysteries and thrillers where light triumphs over darkness, and good always wins out in the end. Was noir like this, she wondered?

“Just the opposite,” I said. “In noir, the main characters want better things for themselves, and feel they deserve them, but try as they might, they continue to make wrong choices and things go from bad to worse.”

She thought for a moment, and said, “Oh, like real life.”

There is more than a smidgeon of truth in my mother-in-law’s response. While most of us at various times throughout our lives find ourselves on the path of wrong choices or become enmeshed in fiascos we never imagined, we don’t go so far as to be involved in a nightmare that includes elements of sex, greed, and murder.

But those are the main ingredients that color the lives of the characters in noir fiction and that’s what makes those characters fun to write. I don’t want to live their lives, but these people that show up in my stories fascinate me, and I do have empathy for them. Something happened to them but what? What prompts someone to go that far? What made them sway to the dark side? Or were they born that way?

I’ve never been arrested. But as a teen, during a dark period of my life when my parents were splitting up and my dad was dying from emphysema, the kids in my cohort were into speed or heroin and I sampled a bit—speed, not heroin. I wasn’t into downers.

Some of them went to juvie and others to jail. I’ve fallen out of touch with all of them though I occasionally learn that some recovered. But most are dead from ODing or from wearing their bodies down with drugs.

Thankfully, I was plucked from that path by some unnamed force and yanked away from the drain. Yet, I know first-hand what it’s like and I knew versions of the people I write about. In my stories, my characters are often composites of people from my past though sometimes they arrive whole cloth. The situations I write about tend to be rooted in something I, or someone I know, has been through. Real life seeds my writing and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

#

People who don’t know me well, or know much about my past, ask why I lean to the dark side in my fiction. I seem so … well-adjusted, they say. Whatever that means. I’ve been married for 31 years, have a grown son, a stepson, a 20-year-old cat, and teach writing at the university-level. I’ve hosted my podcast, Writers on Writing, 20-plus years. I’ve never been arrested or been to jail. “Why noir?” they insist on knowing.

I wrote literary fiction in college and but had a hard time getting my stories published. A lot of characters talked in those stories but not much happened. Then I discovered noir. Crime writer Gary Phillips invited me to contribute a story to Orange County Noir (Akashic, 2010) and I accepted. I was familiar with noir movies and the novels of James M. Cain, but I was green about the form, so I spent one summer studying, reading, and writing. Then something unexpected happened. A crime occurred in my story. Instead of characters talking and not doing much but drink and smoke cigarettes, now they drank and smoked cigarettes and did questionable and nefarious things.

When I walk down the streets of my neighborhood and pass a car in a driveway that’s running but no driver is around, I think: someone could steal that car. When I see kids at the park with nannies who aren’t paying attention, I think: someone could grab a kid and no one would ever know. Does everyone think this way or only writers of dark fiction?

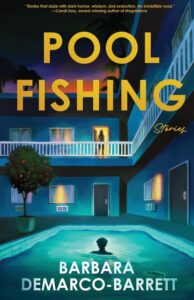

I glanced down the list of titles in my new story collection, Pool Fishing, and saw that all of my stories have protagonists and side characters with shaky morals. They might volunteer at soup kitchens, but they’re not beyond doing something illegal to further their own goals. I’ve known these people firsthand. Haven’t we all? Outsiders aren’t foreigners to me. in central Pennsylvania where I grew up, it seemed everyone was a WASP, and my Italian-Catholic family were the outsiders.

It must have begun with my dad, a bigamist 30 years older than my mother. When my older brother was an infant, Mom received a mysterious phone call from a woman who said, “Your husband has another family in Forest Hills, New York.” Mom confronted my father who admitted that yes, he did have another family—a wife of 25 years, children who were as old as her, grandchildren even. Mom left him, taking with her my newborn older brother. After Dad divorced his first wife, Mom and he remarried.

But his carrying on didn’t end there. Dad, a native Sicilian, had at least one woman on the side during most of their marriage, which was why many nights as a child I fell asleep to the sound of their arguing. How could this history not form my being on a molecular level. It colors my stories dark. My bipolar, character-disordered mother had her own problems.

I was an outsider, again, when my dad lost his good position due to age and Mom found a job in the cafeteria of a Ford Philco plant in North Wales, PA. One friend’s mom wouldn’t let us hang out because my family was no longer in the right class.

#

When I was 16, I had a meth head boyfriend who finds his way into my stories without my even trying. He shows up in “Crazy for You,” “Doors,” and “Blue Martini.”

Newly graduated from college, I lived in San Francisco and needed more money than my baking job afforded me, so a friend tried to convince me to dance/strip. That friend and the strip club show up in “Pink Aviary.” I never did take the job.

My brother, who had more than a smidge of a problem with embezzling, showed up in the brother character in “The Water Holds You Still,” and my protagonist in “Rowboat,” went to jail for embezzling from her boss. More than a little of my brother found his way into her. Would I be obsessed with embezzling as a character trait if I hadn’t dealt with it at length him?

A friendship-ending confrontation with a friend from my former book group found its way into “Rowboat,” though unlike my protagonist, I try to poison or drown her. I didn’t take revenge or book an appointment with a therapist to process the upset. I wrote a story. That’s what fiction is for. I wouldn’t call it cathartic, writing noir, but it provides a sort of relief in some strange way, as though writing brought me one step closer to closure.

In “Noise,” my protagonist Coco can’t accept that the cool guy next door doesn’t notice her. Haven’t we all experienced that—being overlooked by someone we’re interested in—though hopefully we don’t deal with being rejection by drugging that person as Coco does.

In the title story, “Pool Fishing,” my protagonist rescues a beer bottle from the apartment house pool and finds a note inside. It sets her on a mission to find the person who wrote that note. I didn’t mean to write a story based on something I went through but it must have had an influence. When my son Travis was small, we’d go to the park to play baseball. One day, with his big wooden bat slung over my shoulder, we came upon a dad from Travis’s school threatening another mom because she was trying to steal his nanny. So Newport Beach! Without thinking, I held the bat up as if I was about to swing, and said, “Back away!” He backed away. There’s a bat in “Pool Fishing,” and unlike me, my protagonist swings.

I based an experience I had with an animal rights group in “Animals.” On one Black Friday years ago, I took part in a raid on a fur store. We marched into the store chanting and holding signs plastered with pictures of minks caught in traps. In my story, the protest becomes a raid of an animal testing lab.

In “Hunting Season,” written prior to Covid, the internet has collapsed, and journalists as well as any type of equipment that creates newspapers, newsletters, and magazines are outlawed. My protagonist Zoe collects typewriters, one of which causes big trouble for her boyfriend Wade. At this writing, my typewriter collection sits at 10, down from 35. I hope this story wasn’t prescient, because sometimes it seems as if that’s where the U.S. is headed.

It’s not something I set out to do when I begin a story. I don’t tell myself, Okay, write a situation where someone knocks out the bad guy with a baseball bat or write a character who embezzled like Sam. It just happens.

Stories also emerge from my fears. I look at “Sandman,” with its serial killer pedophile villain and remember how, when my son was small, I worried something might happen to him, so when we wanted to move, I looked up Megan’s Law to see if the new city had any registered sex offenders and where they lived. “Sandman,” a story requested for a horror anthology, needed to be based on a horror film from 1919 to 1931. Of course I picked M, with Peter Lorre playing a pedophile. I could have picked any other.

Or losing custody of your child to your spouse—thankfully not something I ever went through. But when I was 23, an older friend lost her kids to her ex. While she wasn’t as character-disordered as Anna in “Making Peanuts at Pachanga,” who lost her boy and might get him back, my friend never did gain custody of her boys.

Stories resolve questions about the paths not taken. What if I had stayed with the speed-addicted boy of my youth? What if I’d succumbed to the allure of drugs, as so many of my friends did, or took that stripping job after all? Stories let us play out all the lives we didn’t choose to lead, letting us peer behind all those doors we closed when we went in a different direction.

Writing dark fiction is one way to deal with the terror we feel when we watch the news. We create scenarios to purge ourselves. We also get to observe situations to see how things turn out. As my Writers on Writing podcast cohost Marrie Stone says, “Stories are safe playgrounds to test stuff out. Fiction is like life—with guardrails.”

#

Patricia Highsmith’s characters were outsiders. This writer of 22 novels and dozens of short stories including The Talented Mr. Ripley, Carol (the book was called The Price of Salt), and Strangers on a Train, had little interest in successful, well-adjusted people. They bored her. I’m right there with her. It may be that her struggles with money until later in life influenced her perspective on wealth and society. She was interested in psychological drama and complex characters yet considered her books entertainments. She wasn’t interested in high-brow prose or getting across a message. I’m with her there, too.

I thought of Highsmith recently when a friend who’s read much of my noir fiction suggested I write something uplifting and “enlightening.”

“Enlightening?” I said. “I wouldn’t know how.”

What does the word “enlightening” even mean? I’d recently reread Presumed Innocent, one of my favorite novels, and found it enlightening in Turow’s exploration of human behavior, as well as a marvel in the author’s use of the first person, present tense point of view. But I don’t think this was the sort of enlightenment my friend was talking about.

And honestly, I’m not interested. More fascinating to me are characters experiencing a moral breakdown, those unable to rise above their baser instincts. I don’t want to hang out with these people or have them over to dinner, but I want to spend time with them on the page. Gary Phillips says, “Noir is about us acting on our baser instincts, so we can’t help but be fascinated. There’s a vicarious thrill that reminds us we could be one of the principals in a noir story, but we know we’d get burned.”

#

Settings are almost as important for me in noir as the situations the characters find themselves in. The settings in my stories run from shoddy to upscale and have everything to do with the characters and what they end up doing. Converted motels on streets across from auto body shops on the wrong side of town in suburban Orange County, California, where rattlesnakes hide; casino hotels in the Mojave and Sonoran deserts and high-end mid-century modern neighborhoods in Palm Springs with swimming pools that are both entrancing and deadly. I love noir from the ‘40s and ‘50s, those seedy back alleys. But some of my favorite noir has the sun giving sunburns, everyone needing sunglasses, women in bathing suits with beauty all around.

In my fiction, I dredge up places I’ve been, things I’ve observed or interacted with. Doors, for instance. In my story, “Doors,” a door at a motel in Wildwood, New Jersey, where I went with my meth head boyfriend shows up. We popped acid and I became obsessed with the door, to the room, marveling at the whorls in the grain, but for him it was just a door, and that sent my thus lovely colorful acid trip down a dark hole. I ran outside and contemplated running into traffic. He followed and talked me down. That door and a different, more pleasant acid trip, found their way into the story.

Writers have heard—and say, ad nauseum—everything is material, yet how true it is. No one else has your past, your frame of reference, your experience of the people you’ve met and the places you’ve been. Those are gifts for a writer. You never have to grapple for characters, situations, or settings because they’re all there, in the file cabinet of your brain.

My mother-in-law was drawn to novels with tidy endings where the good guys triumph, while I desire messiness and death. The things that disturbed her comfort me. Who can say why? Our mental filing cabinets crave order and truth, to make sense of the world’s nonsense. For me, based on my body of experiences—the people I’ve met, places I’ve lived, and things I’ve seen—that means strolling down all those dark alleys not taken and seeing where they lead, all the while knowing my own life turned out fine—so far.

***