No matter what some folks say, there is nothing sexy about dying young. Whether its James Dean crashing his ride in 1955, Jimi Hendrix choking on vomit in 1970 or famed painter Jean-Michel Basquiat overdosing on heroin in his New York City home on August 12, 1988, there are no beautiful corpses. Only 27-years-old when he took his last gasp, the dreadlocked brother was scheduled to attend a Run-DMC concert with friends. That afternoon Basquiat’s girlfriend found him unconscious on the bedroom floor. He was pronounced dead on arrival at Cabrini Medical Center.

I’ve always believed that no one starts doing drugs hoping to become a junkie. Usually it starts off as fun or a release or an escape, but no one imagines the day when the drugs take control of their mind, body and soul. As a boy growing-up in Harlem I saw my share of arm scratching, nose sniffling, cranium nodding dope fiends, “hop heads,” as my mom’s Uncle Richard used to call them. Still, those were cats who believed they had no future whereas to the outside world Jean-Michel had everything.

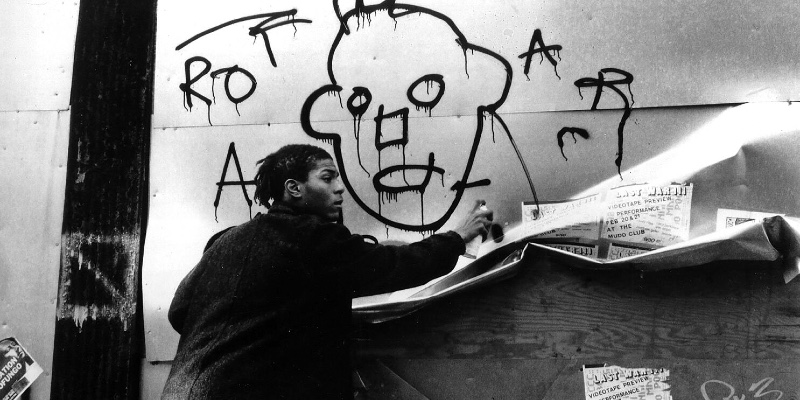

Basquiat began his art career alongside City-As-School High School buddy Al Diez when they both wrote SAMO graff on the walls of the Lower East Side in 1976. His other homeboy Fab Five Freddy told me how they would make the scene at SoHo art openings just to eat. However, a few years later he was being celebrated in the art world and on the gossip pages. While he painted his ass off in a style that has always been equally loved and hated, he also played in a noisy rock band called Gray, travelled extensively throughout the world, collaborated with his friend Andy Warhol and served as inspiration to many artists of color, including myself.

“For me, Basquiat’s work was mind-boggling,” said curator Franklin Sirmans. “He might’ve been influenced by pop and Warhol, but Basquiat’s work elevated the whole sphere and discourse around visual arts.” In addition to his prolific output, Basquiat was often seen at ritzy eateries Mr. Chow or The Odeon, styling and profiling with other downtown scenesters including Madonna and Keith Haring.

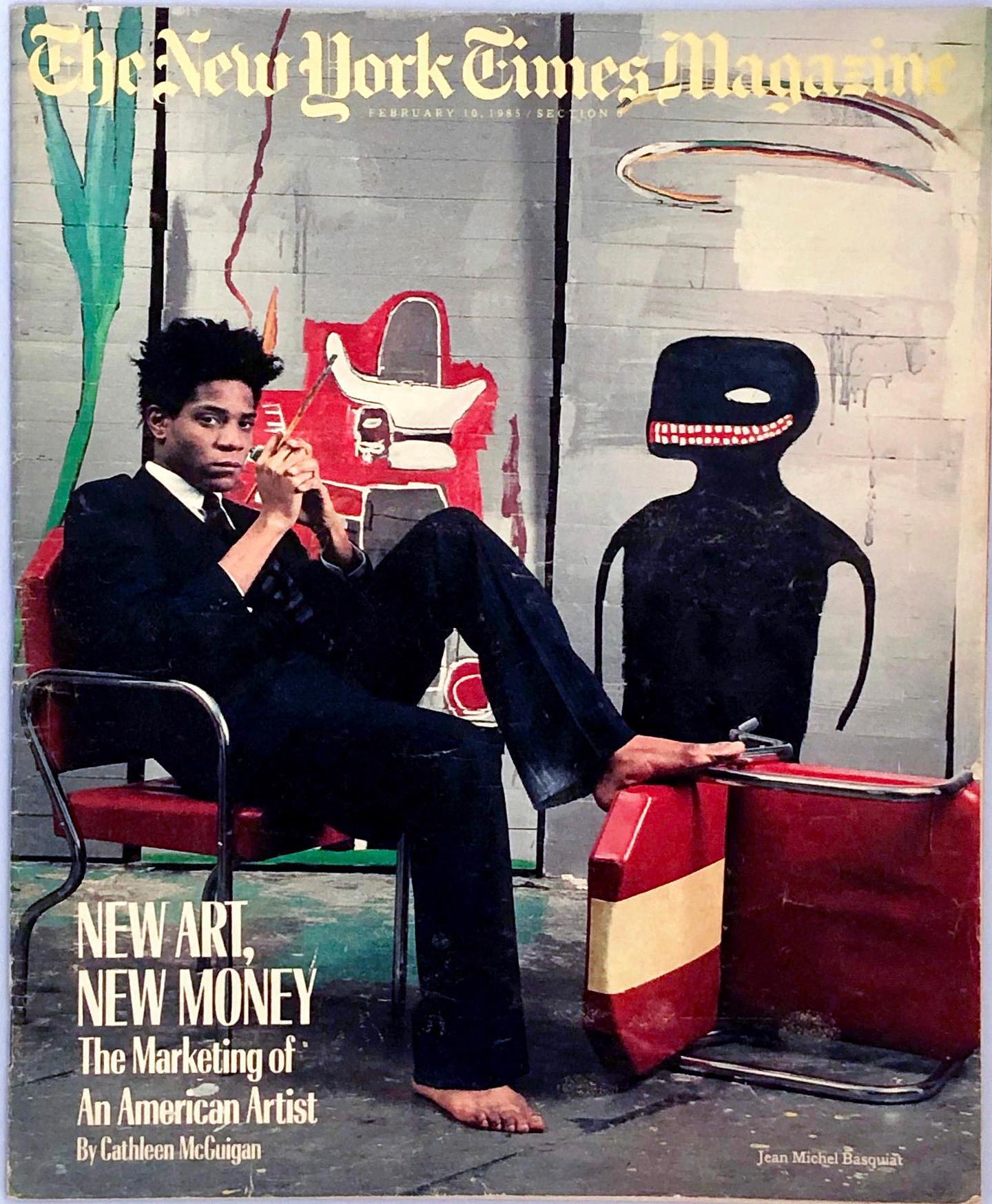

The first time I saw Basquiat was on the cover of The New York Times magazine section in 1985. Shot by Lizzie Himmel, he posed in front of one of his paintings barefoot in an Armani suit, I became obsessed with the brother. Though this was an era of New York City at its worst with buildings on the Lower East Side crumbling (“It looks like a warzone,” he observed in the film Downtown 81) high crime and high times with crack being introduced the year before, but Basquiat looked regal as royalty.

A few months later, after an opening at the Mary Boone Gallery on March 2, 1985, I was invited to his massive dwelling on Great Jones Street. A former stable owned by Warhol, there were a bunch of paintings leaning against the wall while a few feet from where a dj soub dub music and drunken people danced. To this day, I beat myself up for not being more aggressive and introducing myself. Three years later, on a hot August day, Basquiat was dead.

***

Born to a Haitian father and a Puerto Rican mother, who took him to museums when he was a child, Basquiat began drawing as a kid. His mother Matilda, a stunning woman before mental illness brought her down, was the primary reason young Jean became interested in art. Though there hasn’t been a lot written her, in 2023 when I was researching and writing the Basquiat-inspired short story “Riding With Death” (based on a painting of the same name) for literary magazine Obsidian 47.1, I discovered many interesting facts about Mrs. Basquiat.

Jean-Michel told loving stories about his mother taking him on journeys through the city as they travelled to the Brooklyn Museum, The Met or the Guggenheim where they spent hours surrounded by the secret worlds captured in the canvases of Caravaggio, Picasso and Cy Twombly. Silently mother and son stared at the vibrant images on the walls as though the pictures whispered vast secrets about our world as well as heaven and hell.

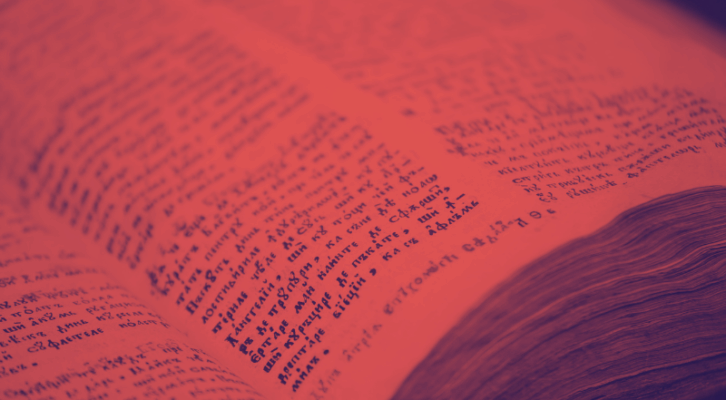

When Jean was eight he was hit by a car and spent weeks in the hospital where his spleen was removed. Matilda bought a used copy of Grey’s Anatomy to the hospital as a gift. His mother wanted her bright boy who loved art to see drawings of the body, inside and out, to know, or at least try to understand, what was happening to him.

Slowly turning the pages illustrated by Henry Vandyke Carter, he stared in fascination at the detailed pen and ink renderings. Lying in bed Jean stared at the drawings for hours. A decade later those medical illustrations began to appear in his work. Grey’s Anatomy would, until the end of his life, be Jean’s most treasured possession.

Later when she became sick, Jean visited her in various mental wards where she sat for hours imitating the whistling of birds. After his mother was institutionalized Basquiat ran away, choosing to become homeless instead of living in the Park Slope brownstone with his disciplinarian daddy, who he blamed for his mother’s illness. Somehow, he kept going to school.

“City As School,” said Al Diaz, “was a pretty arty place, an alternative school where lots of freakish people went. There were musicians, artists and all kinds of folks who were off to the left. Jean was shy and awkward, but we hung-out and smoked weed. Part of the Jean-Michel mythology is that he was an underprivileged street kid, but he wasn’t poor. His father was an upper middle class accountant, but he had a nasty attitude, which is why Jean left home.”

Although Basquiat and Diaz later had a minor falling-out during their graffiti years, the two remained friends until the end. “Jean-Michel gave us all hope of making it. But, he wasn’t a very happy person and his addiction became like a slow suicide.”

***

Basquiat’s best paintings can best described as “hip-hop on canvas.” His art was filled with pop culture references, musical tributes, African imaginary, strange poetry, brand logos, comic book characters and allusions to death. Late actress and curator Patti Astor, who co-starred in the classic hip-hop movie Wild Style, first met Jean-Michel hanging-out at the Mudd Club. In 1982, she gave the young artist a show at her Lower East Side art space The Fun Gallery.

“I first met Jean Michel Basquiat in 1980 on the stairway up to the VIP Room of the Mudd Club when he was homeless,” Astor told me in 2010. “I was already an underground film star and was flirting with him, teasing him about his weird hairdo. Only a few months later at the landmark ‘Beyond Words’ (art) show at that very same spot I saw his ‘Flats Fixed’ drawing and realized he was a genius artist. Remember the company he was in, Keith Haring, Kenny Scharf, LEE, Futura, DONDI, A-One, Rammellzee and FAB but I just knew.”

A few months later, Astor invited Basquiat to display his work at the FUN Gallery. “At that FUN show I was begging collectors to buy 6 ft. paintings for $3,000, but no. These same collectors now claim to have ‘discovered’ Jean Michel. We did break his record at the time with a $10,000 sale.” Two decades later, his work would be sold for millions. “There was driven talent of a young man who I’m convinced will be recognized as the greatest artist of the modern era.”

***

In the 36 years that has passed since Basquiat’s premature demise, his celebrity status, as well as the value of his paintings, has risen considerably. “Basquiat was like the Tupac of the art world,” painter Danny Simmons said. “Like Pac’s numerous unreleased tracks, at the time of Basquiat’s death he left behind more than a thousand paintings and drawings, many still unseen.”

Simmon’s 2004 Basquiat inspired art novel Three Days As the Crow Flies is a brilliant depiction of the world of NYC Black bohemians and the art world in the 1980s. “Even today, the art world can be closed off to people of color, but Jean was a pioneer and a great inspiration.”

Basquiat’s buddy Cey Adams, a former graff artist turned graphic designer and painter, said, “Basquiat’s rise was similar to Jay-Z’s or Biggie’s. He built an amazing career and at the time of his death he left over a thousand paintings and drawings. Basquiat’s mind was in a different place. My favorite show was the one Patti Astor did for him at the Fun Gallery. Not many people were willing to give an artist of color such a big show. I remember seeing his work and realizing Basquiat’s mind was in a different place. His work gave me hope. Jean was very intelligent and would call “bullshit” when he saw it. I was sad when he died. He was so talented and young, and there was much energy in his work.”

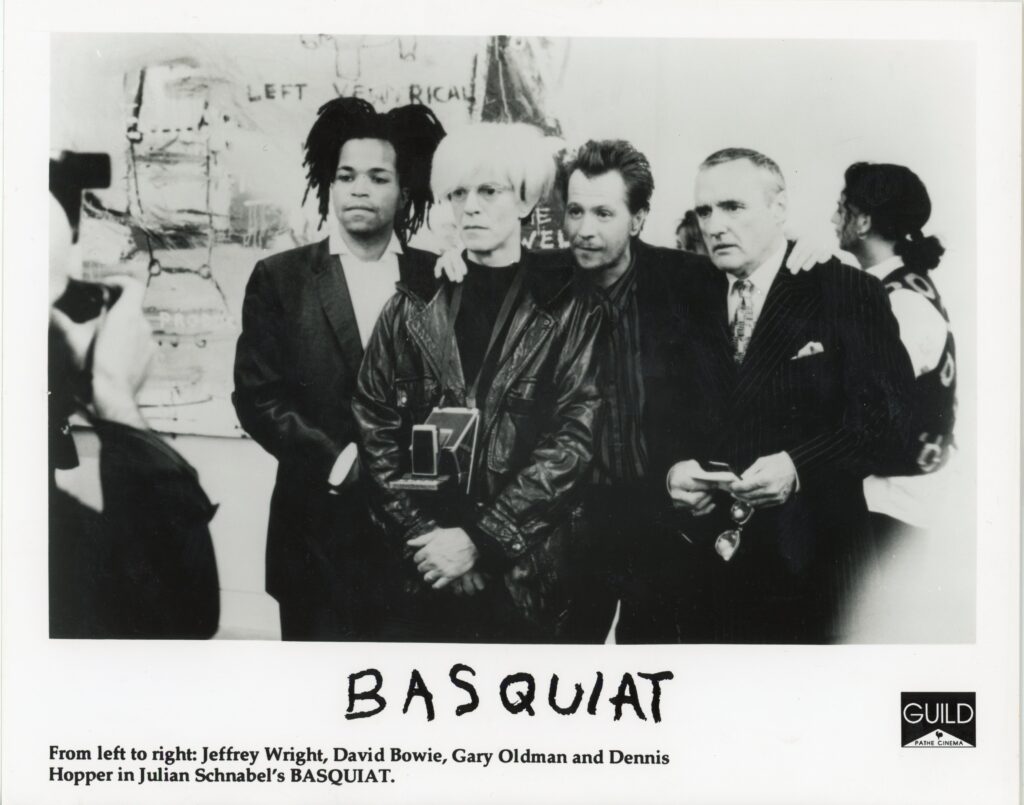

This summer will be the 29th anniversary of the 1996 bio-flick Basquiat, the first film made about the iconic artist. Starring acclaimed actor Jeffrey Wright in his first major role, the film marked the directorial debut of fellow painter Julian Schnabel. “I wanted to make a requiem for Jean-Michel,” Schnabel told Charlie Rose in August, 1996. “I hope to make people curious…this is an educational film.”

Earlier this year Schnabel remastered Basquiat for Criterion, deciding to remix it in black and white. The director got the idea while screening the movie at a film festival and there were problems with the projection. The movie was shown without color. Schnabel fell in love with seeing the film that way, comparing the new version to the work of The Connection/The Cool World director Shirley Clarke.

“The black-and-white version of Basquiat highlights Wright’s acting,” writes Roger Durling in the Criterion booklet essay, “he is magnetic and fully committed, with a detailed physicality of mannerisms and tics that is not showy but amalgamated and critical to understanding the young artist. And the character’s deep hurt is clear—it is in Wright’s soulful eyes and every step he takes.”

When I heard about the black and white version, I snickered to myself remembering a few of Basquiat’s friends who expressed to me that the film showed none of the friendships the artists had with other Black folks: writers, b-boys, emerging rock stars and other artists.

Guitarist Monk Washington, who worked at the trendy club in the ‘80s, remembers a different Basquiat than the one depicted. “I met Jean when I was working as a bus boy at Area,” Washington said. “It was the most popular club in the city and he used to spend mad money there. But, at the time, I had no idea who he was. This was 1985. I got kicked out of my house and Basquiat let me stay with him for a while.

“He was an intelligent man; he wasn’t just about running around. He was a serious dude. The film’s depiction was what they wanted to create, but the man I knew wasn’t afraid of his Blackness. He hung-out with real brothers and you can see that Black pride in all of his work.”

Franklin Sirmans recalled, “When Jeffery Wright was cast in the film, he called me. We knew each other through mutual friends. He was excited and I showed him various books and some video footage of Basquiat. We just met that one time, but I think he approached it the right way. I thought the film lacked complexity and nuance, but Wright made the movie better, because the essence of Basquiat comes across.”

Al Diez said, “For me the movie nailed a few things about Jean, but most people know that he couldn’t stand (director) Julian Schnabel, whose character (Albert Milo as performed by Gary Oldman) in the movie he tries to come across as a mentor and friend, but that’s all bullshit. I first saw the movie when I was in Puerto Rico and it sent chills through me. Jeffrey Wright nailed Jean and that weird stammer he had; later, I ran into Wright on the street and I told him how good he was. The Benico Del Torio character (Benny Dalmau) is based on both me and (actor/director) Vincent Gallo, a fusion of the both of us”

Musician, artist and producer Michael Holman was a young transplant from the west coast when he was introduced to Jean-Michel in 1979. “I met JMB in 1979 at a party called Canel Zone,” Holman said. “That same night, after we had talked for a while, he asked me if I wanted to be in a band and that’s how Gray was born.”

Holman also penned the original screenplay for Basquiat. “In the draft that I initially gave Schnabel, there were scenes that included his graffiti friends Rammellzee, Toxic and others, but he chose to cut those,” Holman said. On the final film his credit was reduced to story development. “Whatever problems I might’ve had with the movie, I’m still glad that Julian made it, because Basquiat was the singular thing that helped propel Jean Michel’s name beyond the art world into the public consciousness. For me, that’s what it was all about.”