When I was 20 years old, I married a man from Texas. If ‘green card’ and ‘alcoholism’ were circles on a Venn diagram, my reason for marrying him would probably fall somewhere in between. I knew he had a violent temper, but in those days, my self-preservation instincts were fairly poor, and I wanted an adventure. I’d grown up in rural England, hooked on Carson McCullers and Flannery O’Connor, and the idea of moving to the Southern US had a kind of rugged appeal. Needless to say, it was a complicated time, but though that marriage has long since ended, and though I have travelled all over – throughout the Rocky Mountains, the Bible Belt, and the Chihuahuan desert – the South still has a kind of haunting magic to it, which I wanted to explore in Our Last Wild Days.

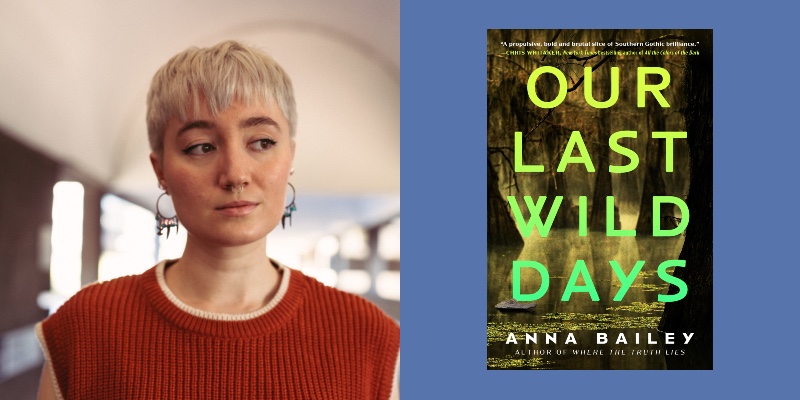

Set in Louisiana, Our Last Wild Days follows a journalist returning to her hometown to investigate the death of her childhood friend – an alligator hunter from an infamous, dangerous family. It’s a novel about guilt and loyalty, but also a love letter to those great lonesome stretches of Southern wilderness, where, for better or worse, anything can happen, and as a writer, my imagination will always want to fill all that empty space. If you look at a map of southern Louisiana, there are very few settlements down there. You’ve got this lonely setting teeming with predators and so few people – but what do those people get up to when they think nobody can see them? In all my writing about America, that is the question I keep coming back to.

The South is a contradictory place, famed globally for both its manners and its intolerance, and as a poorly closeted lesbian, I got helpings of both. Sometimes you get the sense that entire communities are hiding their teeth and claws, and from a crime-writing perspective, that’s really alluring. When you know you’re going to have a setting populated by characters who are already holding something back about themselves, that allows you to feed suspicion and distrust into your story in a way that hopefully feels quite authentic.

However, it really is the landscape that keeps drawing me back to the US in my writing. In Texas, for the most part, I lived on a ranch in a little northeastern town, where I learnt to shoot rats and cower from tornados. That place was mostly sky and distance. Flat for about 600 miles west before you hit the tail of the Rockies in New Mexico, or 200 miles east before you reached forest. It takes almost 13 hours to cross the width of Texas by car – something I did several times, fuelled by Red Bull and blackhearted coffee – and time behaves differently out there. It feels emptier, because you always have so far to go. It can feel like you’ve reached the end of everything and there is nothing but the flatness and you are the last person on Earth, and then you’ll pull into a gas station and eat a corn dog and remember you’re alive.

In the Colorado Rockies, I lived for a time in a cabin in the woods. There were ranks of pine trees no matter which direction you looked, there were bobcats stealing through the back yard, and there was no light pollution, so I got the most unbelievable night skies. There used to be a hummingbird feeder outside, and one night a black bear came and pulled it down to drink the sugar water. It always felt like I was right on the edge of the wild.

I tried to open myself up to living in these places as much as possible. America felt so much bigger and bolder than anywhere I’d experienced before, and I think part of me always knew I’d want to write about it someday, so I kept detailed notes about the way the air smelled, the turns of phrase people used, descriptions of thunderstorms, flash floods, and wild animal encounters.

In Colorado, I worked at a Starbucks in the nearby town, which was about thirteen miles away, so I’d have to get up pretty early to make it to my opening shift at 4:00am, and I remember once driving along this little mountain track in the dark and suddenly coming across a coyote. She was pulling some dead thing across the road. I looked at her, and she looked at me, and she had blood all over her muzzle. When she ran off, I remember very vividly thinking, ‘What if I was eaten by coyotes up here? Nobody would know. It would be days before they even noticed I was missing.’ Part of me loved that, how raw and untamed it felt out there, but it was also terrifying, and that’s definitely a recurring theme in Our Last Wild Days – the freedom that comes with living so cut off from the rest of the world, and the terror of it.

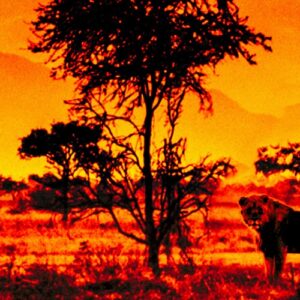

In my case, the terror eventually caught up to me, and I was lucky to get away from my ex-husband when I did, but I still consider him a vital stepping stone into a world that has brought me so much inspiration. I sometimes joke that I have lived it, this American Gothic. I’ve glimpsed the shadowy side of this country, whether as loud men spouting rhetoric from the pulpit, or as the back of my ex-husband’s hand, and I’ve known the weight of a rifle in my arms, just as I’ve known the weight of my friend’s body leaning against me as we drank together under the stars. Our Last Wild Days is my continued exploration of my feelings about this uncanny part of the world. America is a beast. It is the blood-covered coyote in the dark, but I can say that I have looked America in the eye, and even seven years later, I still feel compelled to write down what I saw.

***