I spent a decade with Ed Gein.

Not the real Ed Gein—he died in 1984 in a Wisconsin psychiatric hospital. I spent my decade with the archival Ed Gein: interrogation transcripts, psychiatric evaluations, newspaper accounts from the local papers, and the two definitive biographies by Harold Schechter and Judge Robert Gollmar. I was writing a literary crime novel, trying to reimagine what happened in Plainfield in 1957, trying to get past the accumulated mythology to find something that felt like truth.

Maybe the feeling of truth is the best we can hope for. In a sense, this is the prime driver of all fiction. Isn’t it why we read? No one knows the real truth about anyone else, but fiction can drop us into their life.

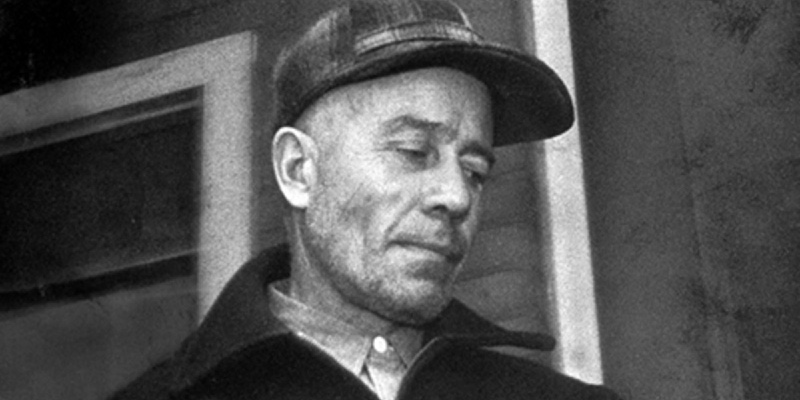

Netflix makes a great case study. Just weeks after I finished my Gein novel, as I began to query agents, Netflix launched Monster: The Ed Gein Story. The timing felt surreal, watching my years of research collide with pop culture in real time. It crystallized something I’d been working through in the writing process: how to make the real Ed Gein visible. The skin masks he wore serve as a grisly metaphor for the cultural and cinematic masks that have hidden him for 70 years.

The Invisible Man

Netflix’s The Ed Gein Story is the third installment in Ryan Murphy’s Monster series, following examinations of Jeffrey Dahmer and the Menendez brothers. Dahmer was a true serial killer—17 victims over 13 years. The Menendez brothers killed only their wealthy parents, but the emergence of court TV pushed their trial into national consciousness.

Gein is different.

As a serial killer, he wasn’t much. Purists will remind you that he doesn’t really qualify. Officially charged with a single murder, he confessed to another from three years earlier. But the lack of understandable human guardrails to his crimes, the complete breakdown of normalcy, and a set of coincidences worthy of Borges, have elevated him to mythological status.

Robert Bloch was mostly known as a pulp magazine writer when he and his wife Marion transplanted from Milwaukee to the small rural town of Weyauwega in central Wisconsin in 1953 to be near her parents. The first coincidence is that fate had moved Robert Bloch less than 35 miles from Ed Gein’s farm.

The second coincidence came on November 18, 1957, when Bloch sat down to work on a novel after three years of silence, having published nothing since moving from the city. Imagine the morning newspaper landing on his front porch. Opening it at his desk next to his typewriter:

Butcher of Plainfield! House of Horrors! Says He Did It For His Mother!

It is hard to exaggerate the hysteria of headlines that Gein inspired. And each article accompanied by photographs of a typical farm house and an unassuming everyman who must have looked, to Bloch, like his neighbors.

The third coincidence is not that Alfred Hitchcock immediately bought the film rights to Psycho, but that no major studio would produce it. Normally Hollywood has no problem with violence. Murder is one of their main plot devices. No, it was the unnatural human intimacy of the violence that bothered them. Which led Hitchcock to put up his own money and use his own television crew to shoot the movie in low-cost black-and-white.

The absence of studio pressure allowed Hitchcock a brutalistic creative freedom that turned the story into a world-wide sensation. For the first time ever, a horror film revealed that the monster is not some strange and fearful creature that the audience can hide from. It is the person who lives next door. It is us.

Gein-as-Norman-Bates was elevated into the cultural pantheon. For a while, the original Gein was still visible through Anthony Perkins’ boyish mask. But there was more to come.

Take three steps forward from Norman Bates in Psycho (1960) to Leatherface in Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) to Buffalo Bill in Silence of the Lambs (1991). These are among the most influential and popular horror films of the past seventy years. Each pulling some piece of truth from Ed Gein’s crimes and isolating, amplifying, mutating, exaggerating, transforming, obliterating. The films were like a palimpsest written over its source. How can anyone look back at Ed Gein through all those layers?

A better question: was it ever possible to see him clearly in his own time? The answer seems to be no.

Fake News

Small towns get an apple pie reputation, but look close and they are simmering with gossip and rivalry and long-running petty feuds. And when something genuinely shocking happens, that thick gossipy filling can boil over.

The inciting incident of my novel, and the event that sent Ed Gein on a three-year spiraling path to his arrest, was the murder of Mary Hogan. She was the line he crossed from perverse behavior to violence. Mary owned a roadside tavern in Pine Grove, six miles north of Gein’s farm, just over the Waushara County line into Portage County.

At the time, Portage County had a problem with its sheriffs. Henry Duda was fired for submitting expenses to the county for prisoners who didn’t exist. The replacement to finish out his term, Harold Thompson, was too old for the job and lost his re-election bid in 1954. One month later, with Thompson still in office as a lame duck—I describe him in my novel: with his wool socks and deck of Rummy cards packed and waiting by the back door—Mary Hogan disappeared from her tavern leaving a trail of blood. Is it any wonder the case went unsolved after a less than vigorous investigation?

The new sheriff of Portage County in 1957 was Herb Wanserski, who had some theories about the Hogan case. He was also up for re-election and needed a dose of good publicity. Herb Wanserski knew about publicity. He had won his election in 1956 based on a saturation marketing campaign featuring photographs of his wife and children in The Stevens Point Journal.

When Bernice Worden disappeared from Worden’s Hardware in Plainfield, the next county down, Herb drew a connection to Mary Hogan. Women missing, blood on the scene, no body found. Herb made sure to elbow his way into the Waushara County investigation run by Sheriff Arthur Schley and snag some prime camera time.

Sheriff Schley was new on the job and in over his head. Only six weeks since he’d been tapped to fill an unexpected vacancy. Schley was a surprise pick with little experience—working for the highway department and as a dancehall inspector— which understandably made him media shy. Herb Wanserski was only too happy to fill in the blanks and tell the press whatever they wanted to hear. Much of the initial misinformation about Gein comes directly from him. It was Wanserski who told the papers that Ed Gein never dug a grave (too diminutive), that Ed Gein didn’t live in his house (too much undisturbed dust), that Ed Gein slept in abandoned barns across the county so there must be dozens more bodies hidden. Wanserski was ready to share his private speculations at the drop of a hat. Said he’d found bones buried in a trash pit behind Gein’s farm (they turned out to be animal). One thing he got right: he pinned Mary Hogan on Gein early on.

Meanwhile, the district attorney confidently announced that Ed Gein was almost certainly a cannibal. It was then that Sheriff Schley made an important decision. He imposed an official ban on talking to the press. All those reporters from across the country gathered in Plainfield and now there was nothing to do—no information forthcoming for days. It wasn’t long before they found other sources. Suddenly everyone in town had a story about Ed Gein.

One man said he was an old family friend who visited Ed’s farm all the time. (This is almost certainly false.) He said Ed used to poke him in his ample belly and tell him he was two pounds shy of being ready to fry up and serve on a platter. Spinsters spun tales of Ed peering in their windows at night. And the press eagerly printed it all.

Adeline Watkins, one of those town spinsters, spoke to reporters about her real acquaintance with Ed Gein. She had known him since childhood, being the same age, and had sat at diners and gone to movies together. Yet she was horrified to read the way new words were put in her mouth in the headlines next day. She complained to Ed Marolla, the editor of the local Plainfield Sun, and he printed a corrective article in the next issue. But it didn’t matter. Adeline remains painted as Ed’s sweetheart to this day—a myth Netflix would revive and amplify 68 years later.

It’s hard to put the marrow back in the bone.

Making History

The mythology of Ed Gein began forming the minute he was arrested in 1957. Much of what we think we know about him comes from nine hours of interviews conducted by the Central State Crime Lab in Madison, Wisconsin by Charlie Wilson and his lie detector expert, Joe Wilimovski. The sessions were taped, but the tapes no longer exist. All that remains are the typed transcripts totaling over 240 pages.

A moral panic spread across America in the late 1980s over the day-care child abuse scandals, a subset of the great Satanic Panic. I remember the Fells Acres Day Care case in Boston. After one child told a story about a secret room in the basement, other children were interviewed and suddenly a slew of tales emerged about magic wands reviving birds and rabbits from the dead, satanic rituals, floating Christmas trees, sexual abuse with forks and spoons, and other fantastical claims. The mother and her adult son who ran the center were found guilty, based entirely on the testimony of four-year-old children. Cases like this repeated across the country.

But within a few years, almost all the cases were dismissed or overturned. What happened is that people began looking at the transcripts of the interviews that produced the testimony used in court. In every single case, all of the outrageous and implausible claims were initiated by the interviewer, usually a nurse or social worker or therapist. When the children denied that anything happened, they were told they were wrong, they only needed to remember better, their friends had already admitted to the stories, or if only they would answer the question again they’d get it right.

Children in particular are easy to lead and eager to please. Highly suggestible. Eager to please. This describes Ed Gein.

When you read the 240 pages of his interview transcript, you can see the same dynamic. Most of the pages, with long blocks of dialogue, show the interviewer doing all the talking. Every major claim that defines the Ed Gein story: choosing victims who looked like his mother, wanting to become his mother, wearing women’s skins to transform into a woman—all of these ideas first come from Joe Wilimovski. Two direct quotes:

On Removing the Head

Joe Wilimovski: Well, do you remember, or do you recall, I mean when you cut her neck—of course, it hung back because it was only held by the bone in the spinal column—that is, of course, probably the time that you drained the blood. So, of course, that would have brought her head very much closer to the ground, and in wrenching the head off from the back bone as I had told you—and you told me earlier that it required much motion on your part, like banding and snapping a wire in two, from those you had taken from the graves—did you let the blood drain from her body when you cut her throat and just hold the head back until the blood drained out so then you could snap her head off?

Ed Gein: That must be.

On Becoming a Woman

Joe Wilimovski: Did you ever consider, Eddie, prior to the passing of your mother that the love that your mother expressed for you and the way you mothered your own mother when she was ill, that you felt that you should have been a woman, or that you would of preferred to have been born a woman or girl?

Ed Gein: That could be, it’s possible.

From these transcripts we also learn that Bernice Worden’s heart was found in a paper bag on the floor of Gein’s bedroom, next to his bed. This is stated directly by Joe Wilimovski, so we can be certain it is true. Yet most retellings of Ed Gein place the heart in a pot on Ed’s stove, keeping the cannibal myth on life support. Netflix is the latest example, and even shows the heart submerged in a soup pot bubbling over a low flame. So where did this fictionalization come from?

Which brings us back to Robert Bloch, who wrote Psycho about Norman Bates. The only time Bloch ever wrote specifically about Gein was a two-page essay titled “The Shambles of Ed Gein” for a pulp magazine in 1962 and republished in several of his collected works since. And it is only from this story that the heart-in-the-pot-on-the- stove idea makes its first appearance, and has now entered lore as a consensus fact.

Echo Chamber

History produces flawed artifacts. Sometimes they are too juicy to ignore. The internet is a game of social telephone, where ideas can be cherry-picked and spread with zero effort, taking on new layers of authority—the authority of replication. Like the heart in a pot on the stove.

Click. Share. It must be true.

Take Augusta Gein. We don’t really know what she looks like. But a deep dive on Google pulls up images of vastly different women. Augusta Gein in a dark fitted- bodice Victorian dress. Another Augusta as a prim blonde with white ruffled collar. The internet has settled on a favorite: a rather mannish and strangely twinkle-eyed woman wearing a beaded necklace with a dark blouse and pleated trim. No attribution or evidence that this is, in fact, Ed Gein’s mother. No source. A purely Baudrillardian simulacrum. The image appears on blogs, in YouTube documentaries, even published articles, presenting itself as reality. Yet it is simply the most repeated image, and each new repetition furthers its authority by circular logic.

There is exactly one verifiable photograph of Augusta Gein. In 1957, Life Magazine photographed the parlor of Ed Gein’s farmhouse after it was finally opened to the light—the room had been boarded up for twelve years since Augusta’s death. The Life photograph captures the entire room, so the framed portrait of a woman hanging on the back wall is small, but it is surely the only authentic image of Augusta Gein. All we get is a glimpse.

Strict and prim, expressionless, her hair pulled tightly in a bun, wearing a dark widow’s blouse buttoned to the neck. She looks out with dull, solid black eyes—surely a trick of the camera—over an abandoned mausoleum walled off like a museum exhibit.

This image of Augusta Gein is at odds with the favored internet version. A woman with an unadorned puritan restraint. Collar buttoned to the neck, hair pulled back without style. A plain face and eyes that seem as heavy-lidded as Ed’s. Unexceptional in every way. Hardly a firebrand. We can digitally blow up the image for a closer look, but that process introduces pixelation, artifacts, errors, a degeneration that mirrors perfectly what happens to information as it replicates across the web. Each new copy introducing distortions until the original becomes lost.

How many times have you read that Ed Gein fashioned lampshades out of human skin? I’ve seen it in almost every online description of items from Gein’s house. He certainly upholstered chairs with skin, and stretched a tom-tom drum of skin over an old quart can. Nipple belt. Check. Window shade pulls made from human lips. Check.

Yet Gein’s farm famously had no electricity or running water. A lampshade requires a lamp, and there were none in his house. If you’ve read that he kept human organs in his refrigerator or his icebox…same problem.

Evelyn Hartley was a 15-year-old babysitter who disappeared from La Crosse, Wisconsin in 1953. The case went unsolved. When Ed Gein was arrested four years later, detectives from La Crosse traveled one hundred miles to question him extensively. They found no evidence linking him to her disappearance. Gein rarely traveled beyond Plainfield, and his documented victims were heavyset middle-aged women, not teenagers.

But on the internet, everyone can be a detective. Theories linking Gein to Evelyn Hartley are too good to drop. You’ll find them written on crime blogs, in Google searches, even Wikipedia lists Evelyn as one of Gein’s potential victims. Once a myth is voiced, the echo chamber feeds it back as a chorus.

The Netflix Effect

Netflix’s Monster: The Ed Gein Story takes all of this accumulated mythology: the tabloid distortions from 1957, the leading questions from the interrogation transcripts, Robert Bloch’s inventions, the serial killer movies, the internet’s conspiracy theories—and stirs them together with the authority and production values of prestige television.

I began working on this article with the idea to watch the Netflix series and list what they got wrong. I dutifully wrote down details, but at a certain point I gave up. Because they got everything wrong. And it’s not as if they missed the mark. They weren’t aiming for the mark. It’s clear the creators didn’t care about Ed Gein, they cared about the mythology of Ed Gein, about what 70 years of cultural hallucination have primed audiences to expect.

I should have known after seeing the trailer.

Netflix circled back to Evelyn Hartley, the teenage babysitter, who has now been conveniently transplanted from La Crosse to Plainfield. We see her stripped to her underwear and tied to a chair in Ed Gein’s workshop. A classic horror film trope. Not only did this never happen, but one of the psychological truisms of Gein is that his disordered farm represents the exteriorization of his mind. That the squalid clutter bears the psychic sediment of his submerged and turbulent thoughts. Yet the room holding Evelyn Hartley is cleaner and more organized than my own basement.

It’s a slippery slope: the Pinterest furnishings, the J.Crew clothes, the fresh-shaven face. Forget about maintaining personal hygiene in a house with no electricity or running water. Netflix sanitized Ed Gein.

Part of the cleanup is his age. Ed was 51 when he killed Bernice Worden, yet he is no older in those scenes (1957) than from the scenes in the mid-1940s when his mother died. A forever man-hunk, well-buffed and groomed. Adeline Watkins was documented in the newspaper record as a 50-year-old, dark-haired woman who looked like the classic stereotype of a small-town librarian. Yet Netflix portrays her throughout the series as the blonde, perpetually perky teenager you might find in a 1970’s remake of Nancy Drew broadcast as an ABC Afternoon Special.

Netflix got big things wrong too, but they can claim to be examining the culture of horror. Ed Gein carries a mummified corpse of his mother to watch him kill Evelyn Hartley in a scene that replays both Psycho and Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Ed Gein never had sex with Bernice Worden. She was celebrated as a hard-nosed “businesswoman of the month” in the local paper, not a ditzy town lush. Ed Gein is shown having sex with corpses—something he denied and for which there is no evidence. He never solved the Bundy murders. Never owned a chainsaw.

The problem is that the next iteration of Gein will reference these scenes as fact. That’s how a feedback loop works: by scraping the body of knowledge and surfacing what is popular and becomes consensus.

Another scene highlights two deformations of the facts. Sheriff Schley invites Deputy Frank Worden to his house for Thanksgiving, because Frank is lost and alone after the death of his mother. As pure entertainment, this works fine. But as a story based on a true history, it is off the mark. First, Frank Worden never found his mother hanging in Ed Gein’s summer kitchen. He wasn’t even there. Sheriff Schley was the one. And second, Frank Worden was actually a Korean War vet with a wife and three children, including 14-year-old Frank Jr.—not quite the mewling character Netflix dreamed up.

The other piece of sloppy research from this single scene is that sheriffs across America at that time were required to live in their jailhouses. The county jails were built with a residence up front and the jail cells in the rear. That’s how the Wautoma jail is set up, and you can visit it today as a museum. Sheriff Schley lived at the jail and was responsible for its upkeep. He would have tucked Gein in at night. His wife would cook the meals for prisoners, do their wash, clean the cells. That’s how the county saved money. So the entire Thanksgiving scene set in the sheriff’s beautiful Victorian home is a writer’s hallucination. And it wasn’t the only one.

Late in the series, there is a diagnosis of schizophrenia. This echoes the ending of Psycho, where the voiceover of the smug psychiatrist attempts to shoehorn Norman Bates into an understandable framework. It is convenient for society to explain away the darkness that seemingly ordinary humans are capable of. And for Netflix to have a permission slip in their pocket to justify their distortions of the historical record. No worry, it was just a hallucination!

Last Remains

When all this gets set aside, who was Ed Gein?

Isolation and neglect are a big part of the answer. Ed’s farm was seven miles west of Plainfield, on an empty stretch of Archer Avenue. The nearest neighbor a mile away.

His farm, fallen into disrepair and decay since his mother died, was never wired for electricity or running water. I’ve lived near there. The winters can sink down to thirty below with wind chill and the summers hit one hundred. Ed was living under nineteenth-century conditions in the second half of the twentieth century.

Another part of the answer is found in a minor detail. When Ed Gein dragged Bernice Worden’s body from the hardware store, he brought the cash register to his farm too. Sheriff Schley asked Ed if he was trying to steal the money—and Ed was mortified.

He said he was only borrowing the cash register. He wanted to take it apart. To get at the gears and see how they worked, how it made the ding sound and popped up the correct amounts. He wanted to know how women worked too. He wanted to take them apart and tinker, to get at the details.

When people live alone, there is no backstop. Nothing to prevent your mind from spiraling off course. No one to warn you, “Stop.” Without his mother to tell him what to do, Ed had no boundaries. Water takes on the shape of its container, and the same is true of Ed’s fluid thoughts. Freedom becomes free fall. Ed Gein didn’t become Ed Gein all at once. It happened over twelve years when there was no one there to lead him back to sanity. And no one there to see it happen.

The closest we can get to Gein’s inner truth is from another taped interview taken the very night he was arrested. He was interrogated in the Wautoma jail on Saturday, November 16, while lawmen from the surrounding five counties pored over his farm.

For some unknown reason, the existence of these tapes remained hidden for sixty-five years. They were placed in a desk drawer, then boxed in storage, and remained in the attic of a retired judge until their discovery several years ago. The tapes contain the only known sample of Ed Gein’s voice (so unlike the helium whisper of the Netflix creation).

Much of the interview is trying to get at why. Why did you dig up graves? Why did you kill Bernice Worden? Why did you dress out her body? What were you thinking?

Ed’s answer is perhaps his most profound. “That’s the thing. I really didn’t think.”

Robert Bloch wrote over Gein in 1959. Hitchcock filmed over Bloch in 1960. Tobe Hooper, Jonathan Demme and countless others added layers. Netflix is just the latest. The skin masks Ed Gein wore have been replaced by the masks we’ve placed on him, and after seventy years, we may never see his face again.

Perhaps we can’t remove those masks because there is nothing underneath. Perhaps Gein was invisible even to himself. All we can hope for now is something that feels true.