In The Impossible Thing, English author Belinda Bauer weaves an original tale of obsession and greed, inspired by a true crime that has remained unsolved for over a century. Set in alternating timelines in 1920s Yorkshire and modern-day Wales, the novel’s central mystery hinges on an extraordinary collection of red guillemot eggs.

At the heart of The Impossible Thing, Celie Sheppard is a penniless and neglected farm girl whose life becomes forever changed when she steals her first sea bird egg in 1926. A century later, odd duck Patrick Fort finds his friend, Nick, and his mother tied up in their remote Welsh cottage and robbed of only one possession: a carved case containing a scarlet egg. Over the course of this tightly plotted and wonderfully imagined mystery, Celie and Patrick’s stories intertwine as they navigate the shadowy and often dangerous world of egg trafficking.

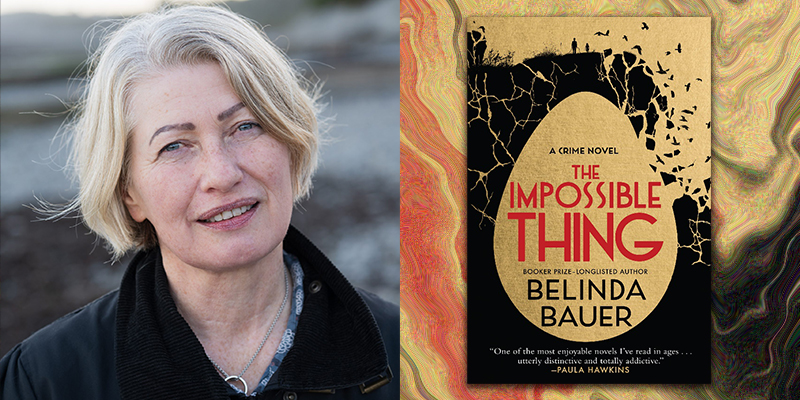

Belinda Bauer is the CWA Gold Dagger Award winner and Booker longlisted author of ten novels. She lives in Wales and spoke with me over Zoom. This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Jenny Bartoy: Where did this peculiar idea come from?

Belinda Bauer: I was driving my car, and on the radio, I heard the tail end of an interview with somebody who was talking about this egg that was stolen from the same bird for thirty years and she never raised a live chick. And I was so overcome with emotion all of a sudden, I had to pull the car over to the side of the road and take a moment. And then [the interviewee] said that even though these were the most famous and expensive eggs ever collected, at a time when egg collecting was a huge hobby and a business as well, once they were sold to this broker at the top of the cliffs, they disappeared and were never seen again. And I was just overcome. I thought, oh my god, this is such a great story. It’s like a crime novel where the victim’s a bird.

So I started to research it at that point, which was 2016, but it was so hard to find anything. It seemed to be a story that had been completely lost in the midst of time, which was great in one way, because I felt I was coming to a fresh mystery, but in another way, it was really hard, because I had to dig deep to try and find even the smallest fragments of detail about this egg. And then, of course, the biggest challenge was to come up with a viable solution to the mystery. It took me a long time to work out what could conceivably have happened to the egg, basing it as much as possible on what I knew about the facts of the case.

Jenny Bartoy: You mentioned doing some research. What did that entail?

Belinda Bauer: The information about these eggs was so hard to come by that it was a lot of work for very small rewards. When I do research in a book, I’ll put in maybe 10% of what I’ve researched. But in this case, I think I put in almost everything. Egg collecting is a very difficult thing to actually research, because it became illegal in this country in the 1950s. By the 1980s, it became illegal even to possess a wild bird egg, and museums rarely display their eggs anymore. But [collecting] is still a crime that carries on today. For my research, I took an officer from the Royal Society for Protection of Birds out to lunch. I showed him my CV, sent him links to my books, and bought him a really nice meal, and he was so hostile to me the whole time. I got the feeling that he didn’t quite believe me. When I finished the book, I sent him a copy to say, thank you very much, and I got the most lovely email from him saying, “I loved the book, it was great!” I’m sure he thought I was an undercover egg collector!

I [also] went to the Natural History Museum at Tring, where the curator spent a day with me, and very kindly showed me more eggs than I ever want to see again in my life. But the hardest bit of research [I did was about] video games. Luckily, my boyfriend’s son is really into that stuff. I had to go to his house and play video games with him and ask him about that jargon. Boy, I was really nervous about getting that right, because to me, that was a real mystery.

Jenny Bartoy: I want to talk a little bit about your characters. Patrick and Celie are unusual protagonists, both sort of fragile in their own way. They’re more underdogs than typical heroes. How did you set out to create these two central characters?

Belinda Bauer: When you start writing a book, you [think], this is the story I want to tell. And then your thought process goes to, who can tell that story the best? Who’s going to give me the best bang for my buck? So that dictates the character that you create. In the case of Celie, it was logistics. I wanted to know why this egg hadn’t been collected by other climbers, so I invented the overhang and the crack [in the cliff, which meant] that nobody else could have collected that egg apart from a very tiny little girl who had the guts to go through the crack. Once I created that situation, that informed the creation of Celie Sheppard. I really enjoyed writing her.

And then Patrick has actually appeared in a previous book of mine. Even though I don’t write series, I do world-build throughout all my books and they have overlaps. So Patrick was introduced in my fourth book, Rubbernecker. People loved him so much in that book and would always come up to me at events and say, When are we going to see Patrick in another book? Can’t he be in your next book? So I’ve been waiting for a long time to find a story where he would be organically involved. I didn’t want to crowbar him in somewhere where he wasn’t suited.

Jenny Bartoy: Patrick is quite endearing in The Impossible Thing. You had me laughing quite a few times. I appreciated the warmth and humor woven through this story that can be quite dark at times.

Belinda Bauer: I like a book that makes me laugh. I think life is funny. So why aren’t people writing funny books? They don’t have to be funny books [per se], but they should be books where people are funny, because in real life, we laugh all the time. I’m always a bit suspicious of a book where nobody’s funny and nobody else laughs at them. It surprises me as well that people don’t write books with more animals in them. Animals are so much a part of our lives, yet hardly anybody [in books] has a pet dog or a rabbit or something like that. So I would bring an animal in wherever I can.

Jenny Bartoy: Let’s talk about craft for a moment. One element that can be tricky to get right in novels is point of view. Through whose lens, whose voice, are we going to tell the story? You write these two close single POVs with Patrick and Celie, where the reader gets emotionally invested. But then you have these other chapters where the POV is omniscient, and you smoothly jump from character to character with more narrative distance, which allows the reader to become a little more removed and judgmental. How strategic are you in choosing POV? What goes into these narrative choices?

Belinda Bauer: I think because of my practice of journalism and then screenwriting, this is natural to me. As far as the characters’ POVs go, yes, you’re absolutely right. There are characters who we’re with emotionally, and there are other characters who are there to move things along — and they are different. Once I’ve chosen my protagonists who are going to allow me to unfold the story the way it needs to unfold, their POV is one thing, but the other is scenes. And I say scenes deliberately, because I write a book like a movie. I’m not writing chapters, I’m editing scenes. And I’m cutting from one character to another character, in just the same way that, in a movie, you have a protagonist who’s going to lead you through the story, but you also cut to other characters who are doing other stuff which needs to happen so that we understand how the story is rolling out on the screen, and then we come back to our character with whom we’re emotionally involved. I think that’s how I construct my books, and that’s probably also why my books don’t have any padding. In screenwriting you’re very restricted, because anything that’s superfluous in the writing is not even going to make it into shooting. Even stuff that’s good enough to make it to shooting is going to end up on the cutting room floor. So every word is fighting for space on the page and on the screen. And I think that has naturally carried through into my book writing where I get in, I say what I need to, and I get out.

Jenny Bartoy: An interesting theme that kept popping up in this book was the importance of human connection and community. Several times, I had an expectation that there would be a conflict, because I think I’ve been programmed to expect that friction narratively, but instead, people worked together beautifully. Instead of fighting, which could be the easy way through the scene, your characters have a human conversation and work things out. That took me by surprise — but also felt important.

Belinda Bauer: I do find that a lot of books I read are peopled with adversarial, unkind characters, and the world’s not like that. And so when I write my books, of course, there are some completely horrible people in them, and they do horrible things to other people and take advantage of them, but there’s also a lot of good people. Apparently I’m very popular with police officers, because when I do write police officers, I write them with humanity. And they may be smart, they may be stupid, they may be drunks, they may be trying to take advantage themselves, but I write them all with humanity. I think for the most part, [people] are trying to do the right thing. So I always like to, when I can, indicate when people are being kind and good to each other, just as much as when they’re being horrible to each other, because I think it’s wearisome to constantly have a barrage of ghastly people fired at you on the pages. It becomes boring and slightly gratuitous violence. You just become inured to it, and you don’t see the light in the shade. It’s only when you see the light that you appreciate the shade and vice versa.