When that unknown assassin squeezed the first trigger back in 1889, blowing Belle Starr from her famous hand-worked leather saddle, they would have had no way of knowing they were inadvertently knocking her right into the pages of history. How could they? At that point, she was only a colorful local character with a checkered past, barely known beyond the frontier settlements of what is today eastern Oklahoma and northern Texas; someone who stirred gossip in neighborhood saloons and provoked headlines in town papers with her ribald antics and frequent brushes with the law. And it very easily could have remained that way, with her name quietly fading into the past, had it not been for one serendipitous event. Two days after her death, the editor of the Fort Smith Elevator, a minuscule Arkansas weekly from the ragged edge of Indian Territory, sent off a dispatch about the killing to a few of the large, metropolitan papers. Including, as it were, the New York Times.

The timing could not have been better. With the 1880s coming to a close and with the “Wild” quickly leaking out of an increasingly tamed West, eastern urbanites held a voracious appetite for salacious true-crime drama from whatever was left of their nation’s vanishing frontier. Yes, heroes sold papers, but villains sold even more, and a villainess—particularly an unabashedly stylish one clad entirely in black velvet and flashing an elaborately plumed hat—well, that was simply too good to pass up. Just three days after her death, the rest of America received its first glimpse of Belle Starr, in the form of an obituary on the front page of the Times, titled “A Desperate Woman Killed.”1 The piece was short and contained as many exaggerations and errors as it did facts. It labeled her “the most desperate woman that ever figured on the borders” (she certainly was not that), stated that she “married Cole Younger directly after the war” (she never married him at all), and also claimed that she “had been arrested for murder and robbery a score of times, but always managed to escape” (also false—she was only ever formally charged three times, for robbery, yes, but never for murder). Yet what the obituary lacked in fact-checking, it made up for in raw titillation. The slim core of truth it conveyed, that a female bandit who ran with famous outlaws had been gunned down in Indian Territory by an unknown assassin, was morsel enough to whet the general public’s appetite for more.

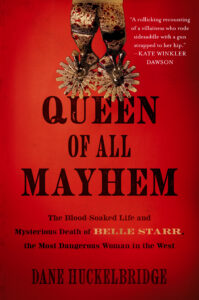

Among those intrigued by the murder was Richard K. Fox, owner of the National Police Gazette, one of the most popular true-crime tabloids of the day—the word “true” being somewhat loosely applied. But while journalistic integrity may not have been one of the publisher’s strong points, knowing how to make a buck was. Recognizing the story’s explosive potential, Fox decided a full-length book was in order. A writer was dispatched immediately to Fort Smith, an egregious amount of creative license was taken, and by that summer, a paperback was produced, titled Bella Starr, the Bandit Queen or the Female Jesse James. Again, the book was far more invention than fact, and even contained “excerpts” from a fabricated diary. It was a work of bombastic fiction, pedaled as something closer to biography, but the audience for Fox’s lurid crime dramas didn’t much seem to care. The slim volume described her as “more amorous than Anthony’s mistress, more relentless than Pharaoh’s daughter, and braver than Joan of Arc.” It went on to claim that “Mother Nature was indulging in one of her rarest freaks, when she produced such a novel specimen of womankind.” And it sold by the thousands.

From there, the legend of Belle Starr effectively—to use the parlance of our times—went viral, gaining in grandiosity with each new serialization and with each fresh telling, affixing her place among the mythological pantheon of the Wild West. In the decades to come, there would be novelizations, epic poems, historical biographies, folk songs, and when the technology arrived, even movies. Belle Starr fever may have reached its peak with the 1941 release of an eponymous film, produced by 20th Century Fox, starring the stunning Gene Tierney, who bore no physical or historical resemblance to the raw-boned middle-aged woman who gave up the ghost on the banks of the South Canadian River. Throughout the final decade of the nineteenth century and the entire first half of the twentieth, Belle Starr, the notorious “Bandit Queen,” captivated America and captured its collective imagination.

Until, rather suddenly, she didn’t. In the postwar years, the name of Belle Starr faded from the national consciousness of the American West. Not entirely—there would always be historians and enthusiasts who knew her story, and her name would continue to ignite sparks of recognition here and there. But her days as a household name, if not a cultural icon, had passed. As to why this occurred, one could posit a number of theories, from the slow death of the Western as a popular American trope, to revisionist historians poking holes in the many biographical embellishments that had gained credence over the years. Perhaps the most convincing reason, however, relates directly to the cultural shifts that were taking place in the United States at that time, as a freshly suburbanized nation stomped the historical mud from its boots and leaned into a new, whitewashed era of cultural puritanism. The cinematic Westerns of the 1950s and ’60s—at least the ones made in the United States—held little room for moral ambiguity or complex sociologies. They were ritualized retellings of the creation myth of the American West, one in which brave Anglo- American settlers, pure of both heart and mind, tamed a wild land, cleansing it of materialistic outlaws and hostile Indians through righteous violence. And primary female characters, almost with- out fail, were paragons of an invented ideal of frontier femininity. Chaste, wholesome, oftentimes schoolteachers or fiancées from back east, they brought decency and lily-white “civilization” to a supposedly lawless and miscegenated land. In effect, they made the West softer, whiter, and safer. More “suburban,” one might even say.

With this in mind, it’s easy to see how Belle Starr—a whiskey-drinking, horse-thieving, gunslinging double widow, who not only bedded a much younger Cherokee man but also forced him to change his surname to match hers upon marriage—might not fit that prevailing paradigm. In the gritty cynicism of a European spaghetti Western, perhaps, and there actually was one such film released in Italy in 1968, retitled in English as The Belle Starr Story. But a John Ford movie? As a love interest for Gary Cooper or John Wayne? It’s unthinkable. The censors of the era would never have allowed it, and forget about the American public at large. When it came to the pop culture depictions of Western heroines and anti-heroines in the latter half of the twentieth century, she was in effect written out of the script. Annie Oakley would receive her own Irving Berlin Broadway musical, Calamity Jane would be featured in a whole slew of movies, not to mention an HBO series, and Big Nose Kate would have cameos in everything from Gunfight at the O.K. Corral to Tombstone—she would even be played once by a decidedly petite-nosed Faye Dunaway. For Belle Starr, however, there was nothing but literary tumbleweed and cinematic crickets. She was all but forgotten.

As far as cultural lacunae go, this one was unfortunate. Because unlike her more celebrated frontier sistren, Belle Starr actually was an outlaw and a gunslinger and an equal partner to some of the most legendary bandits of the era. Indeed, while Annie Oakley was shooting at glass baubles in staged Wild West shows, while Calamity Jane was stumbling drunk and aimless through Deadwood, and while Big Nose Kate was peeking out from behind the curtains of her bedroom during the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, Belle Starr was packing pistols and raising hell, from Texas all the way up to Missouri. Her early chroniclers may have taken some creative liberties, but certain facts are in- controvertible. Belle Starr definitely did harbor and consort with legendary outlaws like Jesse James and Cole Younger. She did marry into a clan of Cherokee warlords, operating, alongside her husband Sam Starr, one of the largest banditry and smuggling rings in the Indian Territory. She did ride sidesaddle and sport a pair of intimidating .45s that she lovingly called her “babies.” And she did face charges of horse theft and armed robbery, even serving prison time for the former, courtesy of the infamous “Hanging Judge” Isaac Parker. Belle Starr may not have received national recognition during her lifetime, but her plumed hat sat squarely in the shaded, overlapping portion of a fascinating historical Venn diagram, containing both storied personas and epochal events. Encircling her own blood-drenched biography like barbed wire is the history of Appalachia, of westward expansion, of the forced removal of the Cherokee, and of the Civil War in the Border States. Her life was lived at the crossroads of all of them.

However, even the dowdiest of historians can prove vulnerable to the allures of raw curiosity and human wonder. And when it comes to writing about Belle Starr’s life, even more compelling than all that dry and weedy history are the rich mysteries that still attend it. It’s true: the story of Belle Starr is rife with unknowns. Not even newspaper articles or census records of the era can be fully trusted. Dates were erased, names were changed, details were invented—sometimes out of carelessness, but often with an agenda in mind. Were one to asterisk every sentence that contained a suspect source or an iffy reference, a book about Belle would become a veritable Milky Way of stars. Practically by necessity, any researched attempt at revealing the details of her life becomes less like writing an academic treatise and more like painting an artistic portrait, shaded as truthfully as possible, while also acknowledging a bit of interpretive brushwork. The West has simply become so mythologized, so aggrandized, that teasing ironclad truths from that tangled skein of frontier yarns is often all but impossible; a little bit of legend will cling to almost any fact. And when it comes to Belle Starr, said legends are usually woven from unanswered questions. Did she really serve as a teenage spy for Con- federate guerrillas? Did she fence horses and provide a hideout for Jesse James? Which of the many armed robberies attributed to her did she actually participate in, if any? And did she ever kill anyone in the process?

All of which leads to the biggest mystery of all: Why? Why did a woman who had considerable advantages in life—a good family, a decent education, solid marriage prospects, a clear path to financial security—choose to pursue a life of crime? Belle Starr very easily could have slipped into the character and mien of a Southern belle, marrying a wealthy landowner or merchant, living comfortably in the boomtown of Dallas. Instead, she chose to consort with bandits, flee from the law, live rough among the Cherokee, and stroll through the streets of one-horse towns, laden with guns.

One could blame the societal damage caused by the Civil War, her family’s move from Missouri to the Texas frontier, or even the death of her older brother Bud—a trauma, most seem to agree, that scarred her for life. And one would not necessarily be wrong. There is probably some truth in each of these suppositions.

The fullest answer, however, as to why Belle Starr chose the outlaw’s way may quite simply be found in her adamant refusal to be cowed by a society that held definitive ideas about how a woman should behave and what she could accomplish. Belle simply had no use for sewing circles or calico dresses; she would not be cosseted inside any farmhouse kitchen or be seen as less than equal to any man. In her own words: “So long had I been estranged from the society of women (whom I thoroughly detest) that I thought I would find it irksome to live in their midst.” The very rights and privileges that nineteenth-century America denied her because of her sex, Belle Starr decided to acquire by the gun. She chose a path different from that which was expected of her—a route that shook with thunder, that was drenched in blood. An exceedingly dangerous road, albeit one upon which she took orders from no man. And here one must also be careful. Because the temptation is certainly there, given the currents and trends of our times, to portray Belle Starr as some kind of proto-feminist Robin Hood or some form of Wild West justice warrior. It would make for some catchy storytelling, that’s true. Belle Starr, however, was neither of these things. And while she may have been bucking the same sorts of societal pressures, it’s hard to imagine that the saloon-loving, Confederacy-sympathizing Belle would have had much in common with the teetotaling Yankee matrons who served as the vanguard of the early women’s rights movement. It’s far more likely she would have threatened to smash their teapots over their heads. The truth, be it comfortable or not, is that Belle Starr was never out for social justice, nor was she an advocate of any cause—she was in it solely for herself. And in that regard, she bore far less resemblance to any Susan B. Anthony than she did to the Irish, Italian, and Jewish gangsters who would emerge half a century later in the ethnic ghettos of Eastern cities. Individuals who, just like her, knew that because of their identity in America, the life they aspired to could never be achieved through honest means. So just like them—but fifty years earlier—Belle Starr chose to achieve it through dishonest ones. She put down her sewing kit and picked up a gun. And the way of the gun did indeed bring her the very freedom she craved: to love whomever she wanted, to live however she pleased, and to take whatever she felt was rightfully hers. But in the end, as was the case with so many outlaws and gangsters, it also led to her ruin, leaving her to gasp out her last breaths face down in that Oklahoma river- bed, riddled with buckshot—and perhaps even regret. And it is that meteoric rise and vertiginous fall, in pursuit of a kind of liberty and equality that her own country refused to grant her, that makes her story so quintessentially American and as relevant today as it was a century and a half ago.

But there’s one more mystery still. A smaller, more personal one, which I hoped, possibly naively, I might solve as well. Growing up, I was often told that Belle Starr was a distant relation on my mother’s side—Scots-Irish farmers who arrived in eastern Texas in covered wagons at roughly the same time Belle did, and who, if the stories are true, also had blood ties to the Cherokee Nation. As to the veracity of both claims, going into this project, I honestly could not say. As I suspect is the case with more than a few American families with deep rural roots, the alleged link to Belle Starr is just one square of trivia in an admittedly checkered past. There is no shortage of outlaws and troublemakers dangling—several by the neck—from our family tree. And while some, like my second cousin Lester, the last man to be hung in Macoupin County, Illinois, I know for a fact to be kin, others—well, it’s harder to say.

I began this book with the hope that the research involved might shed some light on the matter—and that if I was very lucky, somewhere amid all the gunsmoke and betrayal, the war cries and blood spatter, the rumbling of horses and jangling of stolen gold, I might even find an answer.