After mom confessed to binging on Creature Feature/Chiller Theater flicks when she was pregnant with me, I realized that my passion for horror was in the blood. By the time I was seven I’d already seen Night of the Living Dead, which gave me nightmares for a week, and was a regular viewer of The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits, One Step Beyond and horror/monster movies on Saturday nights. As a comic book fan since I was a six year old New York City kid, my tastes eventually swayed from Marvel’s Manhattan-based superheroes to spooky four-color supernatural strips.

While comic book shopping in 1972, I spotted The House of Mystery #204. The cover featured a disgusting multi-eyed green blob creeping across the floor in pursuit of a screaming femme. In the lower right hand corner the illustrator’s signature was a simple “bw” that I later learned belonged Bernie Wrightson, the artist who’d soon become my comic book hero as well as a later inspiration for my writing. Wrightson’s cover became my gateway into the world of 1970s horror comics.

Five years later I had the pleasure of seeing the original pen and ink drawing in its entire poetic, grotesque splendor hanging on the wall of the New York Comic Art Gallery. I stared at that image with the same intensity I’d give the the Mona Lisa three decades later. It was scary, yet moving and damn near alive. Wrightson imagined things and made the horror real. However, the rules of the then-active Comics Code stated, “No comic magazine shall use the word horror or terror in its title,” so the books were referred to as mysteries or suspense.

Still, one look at the stunning visuals told a different tale. Usually drawn by artists whose work was atmospheric and dark, the covers reflected nightmare imagery and other scary scenarios. The DC Comics line The House of Mystery, The Witching Hour and The House of Secrets were all anthologies that contained three short stories written and drawn by various creators. Those books were modeled after the infamous 1950s EC line (Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror and The Haunt of Fear), comics that were drawn by Wally Wood, Al Williamson, Jack Davis, Graham Ingels and Frank Frazetta, amongst others.

Though EC’s horror comics were successful years before, they were were forcibly cancelled in 1954 after the scandalous Seduction of the Innocent by Fredric Wertham condemned them. The anti-comics tome got the attention of parents, teachers and the government when it blamed the four-color delights for juvenile delinquency, sexual perversion and mental illness. There were even Senate Subcommittee Hearings where EC publisher William Gaines was forced to defend his books and company.

The Comics Code was created as way of policing the contents of color comics; at EC the last title standing was Mad, which was transformed into a black and white magazine to escape the censors. A decade later publisher Jim Warren launched the EC inspired magazine Creepy in 1964. He hired Archie Goodwin as editor-in-chief, who brought in former EC artist Joe Orlando as story editor. Orlando was a versatile artist who was best known for illustrating the anti-racism story “Judgment Day” published in Weird Fantasy #18 (March-April 1953). He contributed both art and editorial ideas at Warren, but in 1968 was lured to DC by editorial director Carmine Infantino, who wanted to reintroduce horror comics at the company to provide diversity to the men in tights selections.

Luckily, the then-newer generation of comic book creators had grown-up on a steady diet of EC as well as the fantasy/sci-fi book covers of Frazetta. “Like many other people, I have to blame EC Comics,” Wrightson told Mediascene in 1975. When he was boy growing up in the Dundalk, Maryland, a county of Baltimore, he used to hide the comics from his parents, or his mom would throw them away. “I used go to the corner store and read them until the lady told me to leave. The EC’s twisted my head.”

***

Born Bernard Albert Wrightson on October 27, 1948, he started drawing as a boy. Having fallen in love with the comic strips of Hal Forster (Prince Valiant) and Alex Raymond (Flash Gordon), he was mostly self-taught, though he did watch TV art instructor Jon Gnagy on Saturday mornings and took a correspondence course from the Famous Artists School. He was also inspired by the scary movies that aired on Shocked Theater hosted by Dr. Lucifer and Warren’s Creepy, which published new works by former EC artists Roy G. Krekel, Angelo Torres, Al Williamson, Johnny Craig and Reed Crandall.

Raised Catholic by working-class parents, Wrightson was an only child who attended mass every Sunday and went to Catholic school from first grade through twelfth, an experience he loathed as he tried to sidestep sadistic educators (nuns, priests and lay teachers) who made the kids lives hell. In 1982 Wrightson told The Comics Journal, “I think the whole idea of that kind of parochial education is pretty twisted in a kind of medieval way. Especially for somebody who is slightly sensitive like I was, and like a lot of other kids were too. It really has deep effects.”

Wrightson’s artistic sensibilities were also shaped by Baltimore itself, which has long been in the top ten of spooky American cities. Even on sunny days, it’s a dark place: a southern city with a gothic affectation, a haunted metropolis that feels as though ghosts are everywhere: specters hovering over the row houses, bats soaring over rooftops and creepy alleys where cat sized rats dwell. The town served as an inspiration to Edgar Allan Poe, but was also the place that killed him. Unquestionably, it was the perfect locale for the future “master of the macabre” to be born and spend his coming of age years.

Although I only met Bernie Wrightson once at the 1977 Creation Convention, where he shared an art room with “Studio” mates Jeff Jones, Michael Kaluta and Barry Windsor Smith (that artistic quartet would collectively change the world of comics and graphic design), I was struck by his handsomeness, which was in direct contrast to the “ugly” images he illustrated. Surrounded by fans as well as original paintings and drawings from his recently launched Frankenstein project, he seemed quite nice. Already an art star, he was still as humble as the kid who arrived in New York City eight years before.

After dropping out of high school in 1966, Wrightson worked at the daily newspaper the Baltimore Sun where he drew editorial cartoons and worked in the production department. Also “freelancing for anything and everything,” he contributed illustrations and strips to fanzines Squa Tront and Graphic Showcase, where his 8-page comic “Uncle Bill’s Barrel” (1969) #2. The loony story of a hillbilly alcoholic zombie who keeps raising from the dead to drink the moonshine he left behind, it was seen by ex-EC artist Al Williamson, who was impressed enough to help get Wrightson into the industry.

“Al showed the eight-pager to (DC artist/editor) Dick Giordano, who then took it to Joe Orlando,” Wrightson said. Back then it was a prerequisite to live in New York City if one wanted to work for DC or Marvel. “Dick wrote me a letter saying if I moved to New York, we can get you work in comics. So I decided, why not. I wasn’t doing anything in Baltimore anyway.” In those early years he spelled his name “Berni,” dropping the “e” so he wouldn’t be confused with an Olympic swimmer with the same name.

Originally he was supposed illustrate a new sword-and-sorcery character Nightmaster and was promised $30.00 a page for pencils and inks. “This was 1969 and I had a third-floor walk-up apartment in a neighborhood I later learned was called ‘Needle Row,’ on 77th St., real close to the American Museum of Natural History,” Wrightson told Jon B. Cooke in Comic Book Artist #5 (1999). “I went down to DC and they gave me the first issue of “Nightmaster” in Showcase. I did the first seven pages in pencil and it was so bad, because I froze up, because I felt that my life depended on it—this was my career. I just sweated over every line and the result was just completely overworked and over-thought. It was very stiff and lifeless. I took it in and I could see immediately that everyone’s face fell. I thought that this was it, the shortest career on record, I’m finished.”

Thankfully all the grown-ups in the room were themselves artists and understood Wrightson’s dilemma. “Carmine, very gently and sweetly, took me aside and said, ‘Look, I’ve seen this before and I know exactly what’s going on. We shouldn’t have given you a book right off the bat. You’re intimidated and we’re going to take you off of this. We’ll give the first issue to someone else and we’ll put you on the fillers for the mystery books to break you in.’ And so they gave me to Joe Orlando over in the House of Mystery where I started getting these little two and three-page scripts by Marv Wolfman and Len Wein.”

Wrightson’s first published story was the Wolfman written “The Man Who Murdered Himself” in House of Mystery #179 in 1969. He later credited Orlando with helping to improve and polish his style. “He (Orlando) was the best guy for me and any young artist,” Wrightson said in 1999. “I learned so much from him in my first couple of years in comics. I would bring stuff in and Joe, in his very kind, non-judgmental, gentle way would find a panel on the page and take out his pad of tracing paper that he kept in his desk. He’d take a sheet out and lay it over, and he’d say, “Y’know, you might want to think about this,” and he would redraw the panel very quickly, with stick figures. He would teach composition and short-cuts that enhance the work. He had a way of thinking pictorially that I had never before been exposed to or would have considered. He was there, pointing me very gently in the right direction. He was very much a mentor who really cared about me. I really valued his opinion and I really treasure the experience of having worked with him.”

Wrightson was part of the new generation of comic book artists, now known as “the Bronze Age,” who drew highly stylized and detailed material, making a few of the old timers pissed that these “young turks” made them look bad with their fancy pages. While the older artists had no problem hacking out pages, the new guys were putting sweat and blood into each panel. It was bad enough that these upstart “hippies” didn’t wear suits or ties, but they were also aware that their work had worth, and wanted to be paid better and have their original art returned.

Wrightson’s early short stories “All in the Family” and “Ain’t she Sweet?” showed early admirers where he was headed. “His horror comics were the best, because they hit the perfect balance of realism with stylized and almost cartoony details,” Adam Rowe, curator behind 70s Sci-Fi Art says. The covers too served as his illustration training grounds where he created sinister images that included a frightening vampire (House of Mystery #211), an ancient killer tree (House of Mystery #217), ghoulish zombies (House of Secrets #100) and a crazed warewolf (House of Mystery #231). “If Lovecraft and Poe had been artists and created their works during the 1960s and 1970s, they would’ve been working in the same areas as Wrightson,” Don McGregor wrote in 1975. “He’s the ultimate story-teller of the bizarre.”

Wrightson learned a lot about covers from studying his longtime hero. “Frazetta’s work brought a sort of ruthless intensity to cover illustration, and Wrightson in particular followed in that vein,” says Rowe, author of the forthcoming Worlds Beyond Time: Sci-Fi Art of the 1970s (2022, Abrams Books). “Still, the real Frazetta influence on Wrightson was in how he could all so clearly convey personalities and emotions through the physicality of the characters in his work.” In addition, Wrightson’s also drew a number of frontispieces that featured the horror hosts Cain and Abel.

“It was my idea to do introduction pages to the mystery books,” Wrightson wrote in A Look Back (1979). “If I needed money, I would do two or three of the intro pages and pickup whatever I was getting paid at the time, forty-five, fifty dollars for each of them…I could do it in a night. Almost all of them were knocked out in one night.”

For House of Secret #92 (July, 1971), Wrightson drew the cover of a green creature coming up behind a frightened woman as well the accompanied interior story “Swamp Thing,” the world’s introduction to the popular character. Wrightson was co-creator alongside writer Len Wein of the 8-page period piece that he drew in a week with a little help from friends Alan Weiss, Michael Kaluta and Jeff Jones. “It was one of these things where we all got a chance to pitch in for everyone else when they were up against a deadline,” Wrightson told journalist Bryan Stroud.

The following fall Swamp Thing was given his own book. The short stories had been Wrightson’s training ground, but his style had matured quickly, as though he had, Robert Johnson style, sold his soul at the crossroads in exchange for the genius gene and people loved it. Wrightson’s admirers included kids like me as well as filmmaker George Romero, novelist Stephen King, and future creators Kelley Jones, Mike Mignola, Walking Dead writer Robert Kirkman, director Guillermo del Toro and Neil Gaiman.

Still, it didn’t take long for Wrightson to get bored with doing a regular book. He only lasted on Swamp Thing for ten issues before leaving in June, 1973. He wound-up at Warren Publishing where he was paid more money, worked in black and white, draw originals on a larger scale and was allowed to work on short stories exclusively. His friend and frequent collaborator, writer Bruce Jones, wrote the introduction to the 2011 collection of Creepy Presents: Bernie Wrightson (2011) and reflected back to that era as he gave insight into his buddy’s genius.

“Standing there watching him work, you were too full of awe to realize your teeth were grinding with envy. Cigarette dangling from his mouth, absolutely no reference on his board, Bernie would sit there with only a pencil stub and his imagination and let the magic flow. I vividly remember Jeff Jones coming to me one day with a panel Bernie had done. ‘Bruce, look at this! A guy swinging on a rope between buildings carrying two women on his back! How the hell does he do it?!’ How, indeed? It all came from some hidden vulgate, some deeply personal well from which only he could draw.”

Earlier in Wrightson’s career he’d worked in black and white for the short-lived publications Web of Horror (1969/70), Abyss (1970) and various fanzines, but it was at Warren where he the proved to be a master of the medium. In addition to ink, pen and brush, Wrightson was used wash to breathtaking effect. While there he adapted the works of Edgar Allan Poe (“The Black Cat”), H.P. Lovecraft (“Cool Air”) and began laying the groundwork for his soon-come Frankenstein projects with “The Muck Monster” in 1975. The infamous “psychosexual torment” story “Jenifer,” written by Bruce Jones in 1974 for Creepy #63, was later made into a short film directed by Dario Argento for the Showtime’s Masters of Horror series in 2005.

***

Unfortunately, I didn’t discover the Warren line until a few years later, and had no idea what had become of Wrightson until I stumbled across an ad in The Village Voice in 1977 for the recently opened New York Comic Arts (NYCA) Gallery. That year, New York City was a hellish town, a near bankrupt metropolis dealing with high crime, a serial killer called the Son of Sam, heat waves, arson and a major blackout that turned into a bunch of looting and mini-riots across the city. For me who’d bought the first issue of Heavy Metal in April, turned fourteen in June, started Rice High School in September and tried to sell mystery/horror comic book scripts to DC Comics in October, it was a year of transition.

One October afternoon, I boarded the #101 bus on 125th Street, journeyed through Harlem, Spanish Harlem and the Upper East Side before arriving at 59th Street and 3rd Avenue. NYCA was a block away. Located at 132 East 58th Street, down the block from Bloomingdale’s and around the corner from Fiorucci, there was nothing upscale about the building where the gallery was housed and the dingy doorway often reeked of urine. However, once inside the dark hallway, the staircase led upwards to a small piece of heaven on the second floor. While the gallery sold comics, it wasn’t a comic book shop, but an arts space that recognized that Bristol board users were legitimate artists.

Proprietor Mark Rindner contributed to a change of perspective when he chose to display comic book pages as though they were “real art,” not a crass, throwaway medium. Comic book artists were also considerably low-paid compared to other commercial art fields and publishers often didn’t return their originals, artwork that was trashed, given to fans or warehoused.

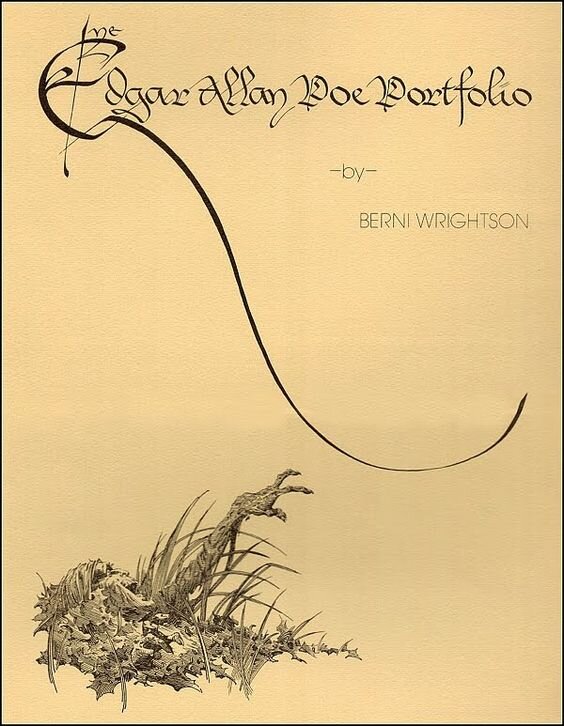

The new generation of upstart comic book artists was tired of being mistreated and began speaking-up about these policies while also branching out by illustrating posters, book covers, album jackets and limited-edition art portfolios. In addition to Wrightson’s comic book work with DC and Warren, he’d also partnered with Christopher (Zavisa) Enterprises to do a series of posters, prints and an Edgar Allan Poe portfolio contained eight full-color 12 x 16 plates which were housed in an illustrated sleeve. It was limited to two thousand copies, signed by Wrightson.

In addition, Zavisa released a series of sci-fi/fantasy/ monster posters beginning in 1975 with “Bad Doin’s in Knuckledowns Lonesome.” Other stand-outs in that series included the demonic “Council to a Minion” and the grisly, but funny as hell “Change” that seemed inspired by Tex Avery cartoons. All of those originals were on sale at the show. Rinder aimed the gallery to appeal to both comic book fans as well as those folks who visited the MoMA or the Guggenheim, to the collectors of Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol and other pop artists who appropriated the culture, but never gave back.

Rinder opened the space the year before with “Fantasies,” a show of Jeff Jones originals. Though he didn’t sell one picture, he made the reckless decision to forge ahead. In its three year history, NYCA Gallery exhibited Michael Kaluta, Neal Adams and Jack Davis. Bernie Wrightson’s show “Somebody Please Stop Me” was advertised as containing “over 200 original paintings, illustrations and comic pages.” He also designed a gory poster with the show’s name scrawled in blood above an ax and decapitated head.

Considering that Wrightson had only been a professional artist for eight years, it seems strange that the then 29-year—old was given a retrospective, but obviously Rindner, who had never run a gallery before, was making up his own rules. Rinder even went through the expense of printing a beautiful catalogue with Wrightson’s written commentary. It featured one of my favorite cover pieces “Coming Out Party,” a graveyard image of a doctor raising a corpse. The ink and magic marker drawing played on two of the artist’s favorite themes–zombies and Frankenstein.

On sale in the front of the gallery, the catalogue shared space with Wrightson’s self-published (Tyrannosaurus Press) “Frankenstein Portfolio,” a project done to fiancé his Mary Shelley/The Monster project. Originally the book was to be self-published, but it would eventually be done by Marvel. Having switched styles to one that, in his own words, was “a cross between a woodcut and a steel engraving,” the portfolio featured six brilliantly detailed illustrations that were reminiscent of Franklin Booth.

“Wrightson worked on his Frankenstein illustrations for seven years, completely unprompted and just because he loved the book, which I think helps explain why they’re so popular,” Adam Rowe says, “The detail is perhaps more intricate, because of how long he spent on it — there’s so much hatching, and his love of the characters really shines through.” In 2019 filmmaker Frank Darabont, who was also an original Walking Dead producer, bought one of the Frankenstein originals for over a million dollars.

In a January, 2021, Comic Arts Live host Bill Cox interviewed Rinder, who recounted that Wrightson had a rabid fanbase of enthusiasts and art collectors who supported the show. “Fans wanted to own his art, but none of this went to his head. He priced the stuff affordable.” While today Wrightson’s work sells from the high six figures to a million, back in 1977 some of his finest pages sold for a few hundred dollars while a painting cost a thousand. The Edgar Allan Poe portfolio paintings were also on display, with the most expensive being “The Cask of Amontillado” at $2,500.

The NYCA show opened on the first of October and ran for the month. Considering that October was the month Poe died and Wrightson was born near Halloween, it was perfect. Before walking through the door of NYCA, I’d never seen an original comic art pages before. However, once inside, I was surrounded by images that wielded “graphic power and inventiveness” while transforming and transporting me. Like a werewolf, I could feel myself changing. Years before I’d ever heard anyone talking about worldbuilding, Wrightson created his own universe of scary monsters and spooky freaks that was vibrant as anything I’d seen in the museums and galleries in the city.

In those days, most comics were printed on cheap pulp paper, so, to be in the presence of the originals was powerful to the point of overpowering. Of course, most of the New York City art world in 1977 had no idea of the graphic revolution bubbling in the world of comics, but Wrightson’s show was the necessary step towards respectability.

***

For the remainder of the decade I followed Bernie Wrightson’s various projects that included Heavy Metal covers, portfolios (Apparitions and a second Frankenstein), collections (Don’t Look Back, Back for More) and the epic art book The Studio, whose publication inspired several generations of sequential superstars who displayed the ability to be stellar fine artists as well. “The Studio was a great collection of talents that pushed comics and illustration art forward at the time,” says Adam Rowe. The short list of my favorite contemporary artists who were children of The Studio era includes Kent Williams, George Pratt, Jon J. Muth and Dave Mack.

In 1980, after a long time away from comics, Wrightson returned with the comical science fiction meets Warner Brother cartoons strip Captain Sternn, which ran in Heavy Metal; the following year it was faithfully adapted for the magazine’s animated film. However, after starting college in the fall of 1981, my tastes in comics changed and I stopped following Wrightson with the same intensity. But, like some folks with church, I eventually found my way back.

In 2001, when I started writing fiction on a regular basis, I went back to Wrightson’s “lush, intricate, otherworldly visions” for inspiration. While decades had passed since I saw the “Somebody Please Stop Me” exhibit, I still felt the impact of Wrightson. Whether it’s the pigeon killing cat in “Simply Beautiful,” the murder of crows invading a small town in “Roses,” the skeleton horse vision in “Riding With Death” or the spooky southern town in the forthcoming femme fatale story “Haunt Me,” most of my fiction, regardless of genre, has a touch of Wrightson in them.

On March 18, 2017, I was devastated when news went out that Bernie Wrightson had died from brain cancer at the age of 68. Though he’d been sick for a few years, and announced his retirement a few months before, it was still a shock. As with David Bowie and Prince the year before, I felt as though a member of the family was gone. However, as with all remarkable artists, Wrightson’s brilliance touched countless souls, inspired so many creative folks, that he has no choice but to live forever.