Dark academia is a literary genre that has its origins in Donna Tartt’s seminal 1992 novel. The Secret History is set in the elite Hampden College in Vermont where a scholarship student attempts to create a new identity among a select group of wealthy and privileged Greek scholars. The gothic architecture, the tailored suits, tweed jackets and plaid skirts offer an aesthetic that is a gateway into an exclusive world of classical literature and bacchanalian excess.

But dark academia is so much more than that. In the shadow of its classical antiquity are big themes – morality, loyalty, coming of age, sexuality, life and death. It’s a time when characters, as students, are at a stage in their lives when they are old enough to understand and philosophise about those topics but also young enough that they don’t have the responsibilities that might conflict with their pursuit of this knowledge. And the campus setting creates an enclosed environment that allows them the time and space to explore and challenge the darker side of life.

In M. L. Rio’s If We Were Villains, a group of seven Shakespearean actors at an elite and secluded conservatory compete for roles and attention until their passions for their art and for each become deadly obsessions. Micah Nemerever’s These Violent Delights follows two opposite yet intellectually equal college freshmen whose friendship and eventual love for each other results in an act of irrevocable violence. Bunny by Mona Awad has another scholarship student at its centre, this time at an Ivy League MFA program where she tries to peel away the layers of obligation, fear, cruelty, jealousy, passion and politeness in a privileged female clique.

At the core of all these stories is the intersection of knowledge and power. The characters strive to better themselves, to rise above even their entitled peers. But there is an inevitable tragedy to this because, while they understand the power inherent in the knowledge or prestige they seek, they are not old enough to have earned the wisdom to wield it. Their fatal flaw is not that they don’t recognise their own weaknesses, it’s that they think they are clever enough to outwit them.

In The Secret History, protagonist Richard Papen considers his tragic flaw to be “a morbid longing for the picturesque at all costs.” Certainly characters are obsessed with how things should appear and aestheticism is pursued without concern for their own personal failings or the limitations of the human condition. The deconstruction of this idea is the central theme of the book and one that flows throughout the dark academia genre. The lengths to which characters are prepared to go to keep up appearances inevitably bring about their downfall as the carefully-constructed facade crumbles under the weight of their own self-deception.

It’s competitive elitism that drives this obsession, and the arrogance inherent in these educational establishments means that dark academia novels are hugely about class. The preoccupation with aesthetics is about the performance of class, something that is generally endemic in academia itself. It’s the outsider who allows us to dissect all of this from an objective perspective, throwing light and shade on the attitudes and behaviours we love to hate.

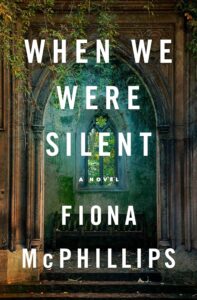

My debut novel, When We Were Silent, is set at Highfield Manor, a private convent school in 1980s Dublin, a time when Ireland lived in the clutches of the Catholic church and keeping up appearances was more important than the morals that underpinned them. When outsider Lou Manson tries to expose a culture of abuse at the school, she discovers that the Highfield elite will go to any lengths to protect their own reputation, even when the consequences are fatal.

Thirty years later, Lou has rebuilt her life after the harrowing events of the so-called “Highfield Affair” when she is called to testify in a new lawsuit against the school. But telling the truth means confronting her own complicity and there is one story she swore she’d never tell…

When We Were Silent looks at the differences between attitudes and behaviours in the 1980s and now, but also at the abiding similarities that these institutions preserve across time. It’s part of the reason for the success of the genre, that glimpse into a timeless fantasy of prestige and privilege that fills us with nostalgia for our own school days and always begs the question: how would we behave in a dark academic setting?

Although Lou goes to Highfield with an agenda, it’s not long before she starts to wonder how much of the school’s worth she can leverage while she’s still there: “I could love it here, if I didn’t already know too much. If I’d been bred to hold my silence like a true Highfield girl. I envy them, the certainty of their position, the rewards offered by the privilege of their birth, and at times it kills me to think what could be mine if I chose to play by their rules.”

And that is the crux of it, the reason for the enduring popularity of dark academia. That any of us would be able to refuse the privilege of it. To understand it, we need to look at our own fatal flaws, our own fascination with the aesthetic. We know these wealthy, entitled characters have a darkness in them and yet we still aspire to have what they have, to want what they want. We might love to hate them but we have to ask ourselves: would we reject their lives if they were offered to us?

***