On January 15, 1947, Betty Bersinger pushed her three-year-old daughter, Anne, in a stroller down a stretch of abandoned, weed-strewn lots on the outskirts of Los Angeles.

The two blocks were pockmarked with rusted bedframes, discarded clothes, and shredded tire rubber but, half-way down, a bright, white form caught her eye.

She turned to her right. There, inches from the sidewalk, in full view on the adjoining patch of grass, lay the horrifically mutilated, cleanly severed, exsanguinated body of Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia.

Some stories have 26-year-old Bersinger running away screaming, while other accounts claim she thought it was just a mannequin and calmly continued on her way, her suspicions rising as she walked down the block.

Regardless, Bersinger called police, triggering what would become the most extensive law enforcement investigation in Los Angeles history – and a mystery that remains unsolved nearly 80 years later.

It’s been the subject of multiple movies, including one star-studded version featuring Scarlett Johansson, Josh Hartnett, and Hilary Swank.

Its legend was fueled by the nightmare of an attention-seeking, sadistic killer on the loose who had posed his severed murder victim in full view for all to see.

It’s a story that’s been repeated endlessly, and always serves as the opening act in every recounting of the Black Dahlia murder. It is Black Dahlia canon.

But something has always gnawed at me.

The two-block, weed-strewn stretch of Norton Avenue on which the body was left in full view was a heavily trafficked street. A streetcar deposited hundreds of commuters just a block away. Cars drove down the street by the tens each hour. Children rode around on their bicycles – as witnessed by Bersinger, herself, that morning.

How could someone not have seen the shocking, mutilated corpse severed in two distinct ‘halves’ laying along the side of the road between sunup at 6.58am and the discovery of the body at 10.50am?

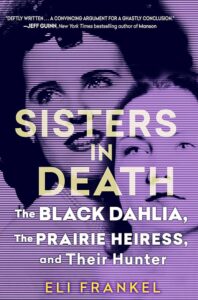

One of the tasks I set for myself in researching what would become my book Sisters In Death was a comprehensive outreach to every child, grandchild, nephew, niece, and grandniece of every major and mid-level player in the Black Dahlia saga. Someone had to know something.

A lot of folks never responded, and I can’t say I blame them. After all, why would a stranger be calling and asking about grandpa?

But many did respond and told me spellbinding tales of their family history. Invariably, the Black Dahlia would enter the conversation. Some were surprised there was a connection to a family member, others were already aware. And some shared long-held family secrets that provided critical insight into the life and murder of Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia.

But there was one bombshell interaction which rewrote everything I thought I knew about the case, propelling my interest and my research forward.

It’s not often a 101-year-old woman hundreds of miles away rewrites everything you know about a murder case you’ve been obsessed with for two decades. But it happened to me.

One of the central mysteries in the case for me lay in a 1971 interview with lead Los Angeles Police Department detective Harry Hansen, in which he revealed that, though most of the findings in the extensive LAPD investigation were printed in the press, there was one fact about the murder which only a handful of detectives knew about.

Purposely held back from the public to this day, it was used in questioning potential suspects, as only the killer would know the answer. Hansen stated: ‘Within this group of questions was one that was relevant yet so bizarre and remote that its answer was beyond even a wild guess, but obvious to the killer.

The small band of detectives in-the-know called it ‘The Key Question.’ Hansen asserted it was not related to any markings on the body nor any internal desecration of the body. All he would reveal is that the mysterious ‘Key’ was related to ‘the condition, appearance or attitude of Elizabeth’s Short’s body at the time it was discovered.’

Detectives asked 500 people the question, and no one ever answered correctly. However, as a seasoned, brilliant detective to the end, Hansen left a clue in his description of the Key Question.

Did you catch it?

‘… at the time it was discovered.”

Why add that detail when so many reporters and officers were present at the crime scene documenting every aspect of the condition, appearance, and attitude of the body in full public view?

Why? Because Hansen wasn’t referring to the well-documented and thoroughly photographed arrival of police personnel and reporters to the crime scene after LAPD radio calls broke news of the severed murder victim.

He was referring to the moment when Betty Bersinger first saw the body.

I wanted to find out if Betty Bersinger had an answer to my burning question – why had no one else seen the body before she had at nearly 11am?

Unsuccessful in contacting her, I tried the next best thing – her daughter Anne, who had been present at the Black Dahlia sighting, but would likely not remember such an event owing to her age at the time.

Anne was warm and welcoming to my inquiries, a pleasant surprise. I figured loads of people had reached out over the years with the same agenda and I would be waiting my place in line. Instead, Anne immediately facilitated contact with her mother, who was willing to answer all my questions, once again to my surprise.

Betty related what happened that morning, her faculties still sharp and memory crystal clear.

What she revealed not only answered my burning question, but provided the answer to Harry Hansen’s Key Question, shaking the case wide open.

When Bersinger arrived at the fateful site on January 15, 1947, she glanced to her right and saw a bright white form which captured her attention.

But it wasn’t laying inches from the sidewalk. It was 12 feet away, hidden in the tall weeds, shielded from view.

Bersinger stepped towards the figure through the patchwork of tall weeds. What she saw was the top, or ‘torso’, half of the victim, her back facing up, her mutilated face hidden from view. The bottom, or ‘legs’, half of the corpse was not in view. The victim’s skin appeared so white from the draining of her blood that Bersinger mistook her for a mannequin.

She continued on her way, but called police from the next house over, to warn them children might be frightened by the discarded object in the weeds.

At 11.09am, the first officers – Frank Perkins and Wayne Fitzgerald – arrived. They, too, mistook the dead body for a mannequin, until they walked into the weeds and realized what was before them.

It would take another five minutes until they radioed back to LAPD’s University Station to report the murder victim. Why did it take them five whole minutes to contact the station from a squad car not 20 feet away?

Because they were moving the body.

With the two halves left face down and likely stacked on top of each other in a thicket of high weeds, the officers had no idea what they were dealing with in the tangle of misshapen body parts.

They pulled the two sections out of the weeds, carried them toward the sidewalk, and laid them down on the adjoining patch of grass, in full, open view, face up, and separated by a gap of approximately 12 inches.

In modern policing, the crime scene would never be disturbed by arriving officers. But in 1947, when two patrol cops discovered a severed body in the weeds, they pulled it out to view the carnage and report back what they found.

This was the change in ‘the condition, appearance or attitude of Elizabeth’s Short’s body at the time it was discovered.’ The key to unlocking The Key Question.

At 11.18am the second set of officers arrived, quickly followed by an army of LAPD personnel and reporters. The images taken that day have become icons of true crime. But the disturbing murder tableau left in full view that day, which would go on to grip the imagination of the world for decades to come, was actually the work of officers Fitzgerald and Perkins.

The real story lay where no one was looking – in the weeds.

Bersinger’s account sent a chill down my spine. I asked why she had never revealed Elizabeth Short’s body had been left hidden in the weeds 12 feet away from the sidewalk, contradicting every narration of the story. Her simple reply: ‘Nobody ever asked.’

Elizabeth Short – the Black Dahlia – had not been left out in full public view, posed by a maniacal killer who wanted to shock the world and terrorize the city, as is almost always assumed.

Tragically – and so true to so many violent crime victims – once the killer’s work was done, he simply discarded her in a lonely, trash-strewn lot, hidden from view, where nobody would bother to look, where nobody would bother to care.

The profile of the killer, which has been endlessly debated by multiple generations, had to be recalibrated. This wasn’t someone seeking attention or power. This was someone working in the shadows and remaining in the shadows. Someone who committed ritualistic acts upon his victim which he did not want deciphered and publicized. It was personal. It was private. And it was over. For now.

When that piece clicked, it made me think of one top suspect in the Black Dahlia investigation: a man who had been a central target of the LAPD and was never cleared, still in their crosshairs when the case went cold 7 years later.

A man who had spent three days with Elizabeth Short just before she famously and mysteriously escaped in fear from Los Angeles a month before her murder.

A man who repeatedly changed his story and lied to police.

A man with a history of brutal assaults on women. A history of stalking. A suspicious death in his family. A man who knew another woman in his hometown of Kansas City who was murdered six years earlier in shockingly similar ways to the murder of Elizabeth Short.

That man’s name was Carl Balsiger. And he was no stranger to me nor any other student of the Black Dahlia murder. In nearly every full account of the case, his name is mentioned – in passing. Plain looking, doughy, gangly, a flat Midwestern voice which belied any suggestion of a homicidal maniac, he slipped through the cracks at every turn of the original investigation and subsequent modern research.

One month before her murder, Elizabeth Short made a hasty exit from the Hollywood apartment building in which she had shared a one room rental. Ostracized by her 7 roommates, tensions had only grown over a marijuana possession bust which had drawn the scrutiny of police. Though having not participated in the reefer madness, a nervous Beth Short wanted to disappear – quick. That morning, she would borrow five dollars from Carl Balsiger to pay her back rent and then accompany him on a road trip to nearby Ventura County. They returned to LA the next day, though Balsiger later falsely claimed to police he merely dropped her off at a motel and then gave her a ride to a bus station.

Immediately, detectives recognized multiple fabrications in his twisted account, and further investigation soon uncovered many more lies. Overwhelmed by the complexity of the Black Dahlia case and the refusal of Kansas City PD to send over its case files, LAPD continued to doggedly pursue Balsiger and keep him at the very top of the suspect list, but would never succeed in solidifying its case and making an arrest.

Why had this suspect with an alibi and a clean lie detector test remained such a central focus of the investigation until the bitter end? Why had no one in the intervening years looked further into his life, specifically the murder of a fellow student at the University of Kansas City whose body bore strikingly similar mutilations to that of Elizabeth Short? I wanted to know more – and then I wanted to know everything. What I uncovered about Carl Balsiger, his life, his character, the murder of his classmate, and his interactions with Elizabeth Short – which predate any known account – put the final puzzle pieces in place.

And it all fit with the stunning revelation Betty Bersinger had provided me nearly 80 years after she stepped into history.

***