In America, especially when it comes to intellectual endeavors — race matters. Black folks are often thought of as being less smart than their white counterparts and, therefore, their work is labeled less important. In the world of literature, fiction by Black authors is rarely required reading in public schools. Many young people of all races don’t realize that Black writers exist until they either discover them on their own or take a higher education class that introduces them to the works of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Richard Wright, Lorraine Hansberry, James Baldwin and countless others. Still, these writers are rarely “important” enough to be part of the canon that values William Shakespeare and Emily Dickinson over August Wilson and Ntozake Shange.

While the rules of game have changed slightly in both academia and the real world, in the 20th century the lit-landscapes were so marginalized that even aspiring scribes of color might’ve believed that Black writers didn’t exist and, if so inspired, it was impossible to become one. This marginalization was even more pronounced in the world of genre writers, especially with science fiction where editors and writers were often more comfortable with characters that were Martians and slimy space creatures than they were with other races.

Staffed and written by white men, diversity wasn’t an issue that concerned them. Hell, even most science fiction films didn’t have any Black characters and basically erased the race from the future. Of course, as editor Sheree Renée Thomas pointed out in her seminal collection of Black science fiction Dark Matter: A Century of Speculative Fiction from the African Diaspora, that exclusion never stopped Black people from being fans of the genre be it books, magazines, films and the four-color pages of DC and Marvel comics.

___________________________________

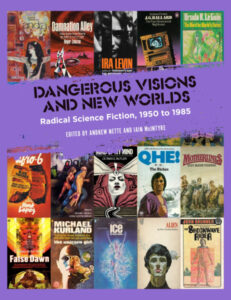

Excerpt from Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Radical Science Fiction, 1950 to 1985, edited by Andrew Nette & Iain McIntyre (PM Press)

Featured image, above: Octavia Butler, 2005, by Nikolas Coukouma

Available on wikimedia, shared by Creative Common license

___________________________________

Years before the term ‘Afrofuturism’ became just another marketing label or TED Talk, early 20th century ‘colored’ writers, most notably Pauline Hopkins’ serialized novel Of One Blood (1902-1903), W. E. B. Du Bois’ 1920 apocalyptic short story ‘The Comet’ and George S. Schuyler’ satirical book Black No More (1931), one of best novels of the Harlem Renaissance, were practitioners of the form.

Yet, unlike H.G. Wells, Mary Shelley or the pulp generation published in the pages of Astounding Stories, edited for decades by the notoriously racist John W. Campbell (who in 1968 said he didn’t think his readers “would be able to relate to a Black main character”), the speculative works of the Black writers remained obscure for years. It wasn’t until the publication of Harlem native Samuel R. Delany’s debut The Jewels of Aptor in 1962, published by Ace Books, that the genre got its first Black star writer.

Only nineteen when his book hit the shelf, Delany would go on to become a Nebula and Hugo award winning author whose work inspired, influenced and taught the next generation. Published in 1975, Delany’s novel Dhalgren has been compared more to James Joyce than Robert A. Heinlein, and serves as just one example of the genre’s possibilities. Along with Thomas Disch, Harlan Ellison, Michael Moorcock and J.G. Ballard, the Sugar Hill kid was a part of the ‘New Wave’ writers who attempted to tell different kinds of stories utilizing various literary techniques and styles.

There was also the Moorcock edited publication New Worlds coming out of England and, later, the shorted lived Delany edited (with his then-wife, poet Marilyn Hacker) Quark. The New Wave writers not only brought modernism/ postmodernism to old fashioned futurism, but they were also impactful in breaking the down racist/sexist walls of oppression, making way for Ursula K. Le Guin (The Left Hand of Darkness, 1969), Joanna Russ (And Chaos Died, 1970) and Sonya Dorman, whose short story “Go, Go, Go, Said the Bird” was published in Harlan Ellison’s landmark Dangerous Visions anthology (1967). Other writers included in that classic collection were Phillip K. Dick, Fritz Leiber and Samuel R. Delany.

Meanwhile, the same year The Jewels of Aptor was published, on the other side of the country in Pasadena, California, a young ‘Negro’ teenager named Octavia Estelle Butler was scribbling stories in notebooks and plotting the complexities of her own future world novels. Butler, having turned fifteen that June 22, was already jotting down ideas that would, more than a decade later, become her book Mind of My Mind. Published in 1977, the novel was the second in her ‘Patternist’ series that began with Patternmaster the year before. She’d started writing a few years before, stories about horses and white men who smoked too much, but, at the ripe age of twelve she slipped into science fiction after a bad B-movie experience. In an oft told story, it was the Brit flick Devil Girl from Mars that sent her scurrying towards the stars and the textual worlds of Robert Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon and John Brunner.

Certainly, as proven by the innovative stories and novels she’d write a few decades later that incorporated African spiritualism and major characters of color, the absence of Blackness within the genre would not deny her dreams, or force her into giving up. Refusing to be written off, Octavia Butler wrote herself into the narrative. “When I began writing science fiction, when I began reading, heck, I wasn’t in any of this stuff I read,” Butler said in 2000. “The only Black people you found were occasional characters or characters who were so feeble-witted that they couldn’t manage anything, anyway.” That same year she told PBS interviewer Charlie Rose that science fiction allowed her freedom, “Because there were no closed doors, no walls.”

Born under the astrological sign of Cancer, she was a stubborn girl/woman when it came to her writing. Coming from a working-class family, Butler didn’t have much, but she held on to the one thing she owned outright: her talent. Butler’s father Laurice James Butler was a shoeshine man who died when she was seven. “He was a huge man who ate too much, drank too much and died young,” Butler told a NPR’s commentator in 1993. She was raised by her religious mother, who was also named Octavia, and attended Baptist church services. The elder Octavia, who’d come to Pasadena when she was a child, had been pregnant four previous times with sons, but her daughter was the only one who survived. She was her mom’s miracle baby, a fighter from the womb.

After her father’s death, Octavia was sent to live on her grandmother’s chicken farm in the High Desert town of Victorville, California for a year. Her grandmother had worked hard cleaning houses, and saved money to buy property. Years later, Butler cited her mother and grandmother as her main inspirations. After moving back into her mother’s home, the elder Octavia took in retired roomers to help pay the bills. While young Octavia was intensely shy around other kids, she got along better with the elderly roomers including an aged woman, a carnival mentalist that she told her stories to. Like a scene from a Ray Bradbury novel, you could easily imagine the two sitting on the Pasadena porch trading tall tales on moonlit nights.

At seventeen Butler left the church and graduated from John Muir High School a few weeks before the Watts Riot in 1965. Having enrolled at Pasadena City College, she became active in the Black student union. According to biographer Gerry Canavan, her experiences at the school contributed to ideas Butler put into her most famous novel. “Kindred was largely influenced by from her time at college where Butler was exposed to the Black Nationalist Movement (1950-1970) and the ideas of fellow African Americans in regards to the discrimination they faced in the past and present. Many of these ideas played a large role in influencing the creation of Kindred,” Canavan wrote.

Throughout her life, whether working minimum wage jobs or publishing novels, Octavia looked after her mother, who worked as a domestic and bought her a Remington typewriter when she was ten. A few of the older people in her community tried to discourage Octavia. A shy, often sad child, teachers labeled her as slow and her Aunt Hazel famously told Butler her dream was impossible.

In Kodi Vonn’s 2018 Medium.com essay on Butler, she wrote, “…upon learning of her niece’s intention to become a writer, she tried to break it gently to the young, dark, complicated girl, saying, ‘Negroes can’t be writers.’ Butler didn’t stop, and, had a drive she would later instill in her human and alien characters.” After finding a copy of Writer magazine on the bus, she read their marketplace section and began submitting her stories to editors.

In 2016, a year-long celebration Butler’s life called Radio Imagination involved a series of events, lectures and performances. It also published a catalog edited by Janet Duckworth and Savannah Wood featuring notes, journals, mantras and pictures from the writer’s archive located in Huntington Library in San Marino, California. An image of Butler reprinted was a school photo of the sad-faced girl, a young woman taller than her peers and often bullied for her otherness, staring blankly into the world as though dying to escape the planet and the cruelty of other kids.

“I wanted to disappear,” Butler told Across the Galaxies (1990) editor Larry McCaffery. “Instead I grew six feet tall.” Gabrielle Bellot noted in a 2017 essay. “Her voice was deeper than that of the girls around her. Its gentle rumbling tone and pitch varying from androgynous to masculine, and students teased her mercilessly. Some of them called her a boy, others a lesbian. (However) Butler did not identify as gay.” Butler seemed to have been as asexual as she was asocial. Like many outsiders, she found refuge in old movies and the library, where she’d been “hiding out” since she was a youngster.

“After I got out of the Peter Pan Room, the first writer I latched on to was Zenna Henderson,” she explained to McCaffery. “(She) wrote about telepathy and other things I was interested in, from the point of view of young women.” Though Henderson is an absent name in current day science fiction discussions, her novels Pilgrimage: The Book of the People (1961) and The People: No Different Flesh (1966) had an impact on Butler’s writing in the Patternist series.

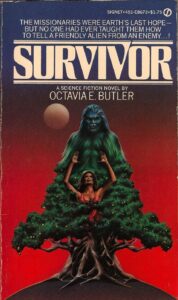

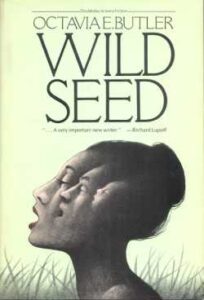

Written out of chronological sequence, those often depressing and scary books, along with Survivor (1978), Wild Seed (1980) and Clay’s Ark (1984), made-up the connected Patternist novels that served as her introduction to the world of science fiction; Butler’s tales were fantastic, but they felt so real. Octavia was more than a writer, she was, as she wrote in her journal in 1987, “…a wordweaver and a worldmaker.”

Though these books were written during the latter part of the New Wave era, Butler’s work lacked the experimental styling and intellectual hijinks of her peers. One might say she was her own ‘wave,’ writing books that were more earthy and grounded. Sometimes it felt as though one needed a PhD in philosophy, semiotics and post-structuralism to get through Delany, while Butler wrote in a way that was more wise than intellectual and could be grasped by a working class person on his/her lunch break at the factory.

In her 2006 essay ‘Parable of the Writer,’ journalist/director dream hampton wrote, “The Patternist series, which culminates in the 1980 magnum opus Wild Seed, features one of literature’s most terrifying villains, the body-snatching Doro. He tracks Anyanwu, a shape-shifter and healer hundreds of years old, to 18th-century Africa. There he forces her to spawn his progeny. She becomes his great love and the only protection her generations of children have from his merciless appetite for fresh flesh. Anyanwu, most at home in her early-twenties body, is beyond fierce: Imagine a Pam Grier who makes the middle passage both as a slave and a dolphin.”

During that same era, Butler, not a fan of writing short stories (“Trying to do it has taught me much more about frustration and despair that I ever wanted to know,” she wrote in 1995), also published ‘Speech Sounds’ (1983), winner of the 1984 Hugo Award for best short story, and ‘Blood Child’ (1984), which won the 1984 Nebula and the 1985 Hugo for best novelette. While ‘Blood Child’ was an otherworldly slave narrative set on a unnamed planet where human men were impregnated by the Tilic creatures, the brilliant ‘Speech Sounds’ was an earthbound tale of the end of world kind when a deadly virus, a familiar theme in Butler’s work, takes away mankind’s ability to communicate and, in the case of more than a few, lowers their intellect considerably.

The main protagonist Rye, after losing her family to the disease, headed to Pasadena in search of her brother. Traveling by one of the rare buses, she’s twenty miles away from her final destination when her world goes haywire. Butler, who never learned to drive, knew a lot the bus lines in her city. In ‘Speech Sounds,’ society was broken, and became worse when people were killed, riots erupted and trust became a synonym for wishful thinking. Still, somehow, Butler managed to bring a tad of unexpected hope to the climax. Both ‘Speech Sounds’ and ‘Blood Child’ were published in Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. “Octavia draws a picture of an all-but-destroyed society that is so vivid that you will find yourself living in it,” editor Shawna McCarthy wrote in the introduction.

Under McCarthy, according to a history of Asimov’s written by Sheila Williams, the magazine “acquired an edgier and more literary and experimental tone.” McCarthy also published work by women writers Connie Willis, Kit Reed, Nancy Kress and Ursula K. Le Guin. McCarthy won a Hugo for Best Professional Editor in 1984. Years later, Octavia Butler’s friend and former teacher Samuel R. Delany, who met her in 1970 when he taught her for a week at the six-week Clarion Writers Workshop in Pennsylvania, cited those stories as her “most important works,” and, while that critical conclusion is debatable, there’s no denying the power of her lean prose in the short form.

It was Butler’s “controlled economy of language and…strong, believable protagonists, many of them Black women,” that brought diverse readers back for more. Still, in the years before Butler was Delany’s student and later peer on equal standing, it was Harlan Ellison who was Butler’s first mentor. According to the Modern Masters of Science Fiction: Octavia Butler by Gerry Canavan, the two met in 1969 when Butler “took a class through the Screen Writers Guild of America ‘Open Door’ Workshop — a program intended as outreach to Black and Latino writers in L.A. — run by Harlan Ellison, himself a brilliant short story writer, editor and television writer since the 50s.

As a devoted Star Trek fan, it would’ve been difficult for Butler to turn down the opportunity to study with the man who wrote the famed 1967 ‘The City on the Edge of Forever’ episode. Ellison wasn’t much impressed with Butler’s skills as a screenwriter, but saw her potential as a storyteller and invited her to Clarion. In addition, he loaned her part of the tuition funds and helped her buy a new typewriter. Coming at a time when fiction programs were relatively new, Clarion began in 1968 and would go on to become the premier sci-fi/fantasy writers Workshop in the country.

Cultural critic Carol Cooper, who was friends with both Butler and Ellison, also studied at Clarion with the famed writer. “Most of us were terrified Harlan would rip us a new one,” Cooper recalled, “and yet he was generous, clever, rigorous, fearless, and incredibly funny. He read us stories, told us jokes and anecdotes, and shredded our wannabe stories in the workshop circle to make them better. He never forgot any of us. His memory was spooky. As was his energy level. People don’t realize how many people he personally got into Clarion, because he believed in their talent. He bought their stories for his anthologies or recommended his students to other editors.”

In 1970, the year that Butler attended Clarion, her classmates included future Marvel Comics/Law & Order scripter Gerry Conway and Vonda N. McIntyre, who’d go on to write the Hugo and Nebula novel Dreamsnake. “Everybody knew her as Estelle,” McIntyre wrote in 2010. “She was tall, quiet, dignified and very shy.” Conway, who too would become a successful writer, said in 2016, “It was obvious even in those early days that her star would burn bright.” In addition to Harlan Ellison and Samuel R. Delany, their instructors included James Sallis, Joanna Russ, Fritz Leiber, Kate Wilhelm, Damon Knight and Robin Scott Wilson.

“When she turned in her first story,” McIntyre continued, “it was clear from the first page that she was an extraordinary writer as well as an extraordinary person. Over the course of the six weeks of the workshop, her talent and range impressed her fellow workshop members as well as her instructors.” Ellison, known as one of the more prolific writers in science fiction, a term he hated preferring ‘speculative fiction’ instead, expected his students to write a story a night, a speed that was frustrating for Butler. Still, she stuck it out.

“When I was at Clarion, Harlan Ellison said if anybody can stop you from being a writer, then don’t be one,” Butler told the New York Times in 1997. Before leaving the workshop, Butler sold two stories. ‘Crossover’, which isn’t exactly a science fiction tale, but does have a Twilight Zone creepiness, was sold to Damon Knight for the Clarion (1971) collection while the novella ‘Childfinder’ was bought by Harlan Ellison for the Last Dangerous Vision, the infamous anthology that was never published. These were Butler’s first sales and she was excited as to be expected.

“The story centers on a woman who senses latent psionic power in children and works to sequester them from an aggressive organization of psis,” essayist Carl Abbott wrote in ‘Pasadena on Her Mind: Octavia E. Butler Reimagines Her Hometown,’ published by the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2019. “Set in a seedy bungalow court that could have matched dozens of places in Butler’s familiar quadrant of the city, the story’s conflict mirrors the racial tensions that Butler experienced in childhood: the ‘child finder’ and the young girl she hopes to protect are African Americans and the Organization are whites. At the story’s climax, several psi-active Black children band together to protect the child finder and form a racially separate psi-active group.”

Though Ellison told Butler in 1970 that publication in his book would launch her career, since the book never materialized the story would remain unpublished until 2014 when Butler’s Unexpected Stories was published. Still, they stayed close friends. Ellison blurbed the 2003 edition of Kindred, calling it, “that rare artifact…the novel one returns to, again and again.”

Growing-up, Butler was a geeky science fiction and comic book fan, but she was also coming of age in a militant era of the Black Panthers, the Watts Riots, Angela Davis, the Black Arts Movement and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song; it all awakened a rebellious spirit within her. While Butler’s work wasn’t considered literary in the way of her more mainstream peers, she was still connected in feminist spirit with writers Toni Morrison (The Bluest Eye, 1971), Alice Walker (Meridian, 1971) and Toni Cade Bambara (Gorilla My Love, 1972), who a few years later became friend, critic and pen pal. Butler even invited Bambara to contribute to Black Futures, an anthology she co-editing together with Martin Greenberg, (who died in 2013) and Charles Waugh that was never completed.

‘Childfinder’ was a precursor to the Psi powered people with their “telepathy, telekinesis, precognition, and other parapsychological activity” in Patternmaster and Mind of My Mind. Just as Psi powers connect many of Butler’s novels, the apocalyptic landscape motif and urban breakdowns of ‘Speech Sounds’ manifests in Clay’s Ark as well as her bestsellers Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1994). Still, while her wild books were praised by the science fiction community, it wasn’t until her stand-alone time travel slave narrative Kindred was published in 1979 that she began developing an audience beyond the limitations of speculative fiction fandom.

With the exception of Survivor, a book she denounced and refused to have reprinted, all of Butler’s books are still in print and her stature in various communities, including LGBT, feminist studies, Afro-pessimists and Black nerds (blerds), continues to grow. While Butler dismissed Survivor, those who’ve read it weren’t offended. “Survivor was my first purchase in 79, and had been her first published novel,” writer Carol Cooper said. “I loved the Patternist series and thought it evolved brilliantly. I found it very psychologically accurate in how it portrayed contemporary Black and white people. My favorite single book was Mind of my Mind followed closely by Wild Seed.”

Butler often played music when she wrote, and friend and fellow writer Tananarive Due could recall visiting her and hearing Motown songs blaring. She also wrote herself positive affirmations of becoming a bestselling author, getting on the bestseller list and not worrying if she had enough money to eat and pay the rent. One of the highlights of the Radio Imagination catalog was the ‘interview’ section ‘Free and Clear’ that journalist Lynell George constructed from Butler’s autobiographical fragments and pieces of memoir. “I understand that writing is my fulfillment and my life, that anything else—any other job—is emotional torture.” Even when Butler didn’t have to work those jobs, her nocturnal nature stuck, and she continued to compose her novels after midnight.

In a 1989 Essence magazine essay ‘Birth of a Writer,’ she spoke of her perseverance as a “positive obsession.” Towards the end of that autobiographical piece, Butler wrote, “At the time nearly all professional science-fiction writers were white men. As much as I loved science fiction and fantasy, what was I doing? Well, whatever it was I couldn’t stop. Positive obsession is not about being able to stop just because you’re afraid and full of doubts. Positive obsession is dangerous. It’s about not being able to stop at all.”

Ten years before publishing that essay, Butler released the novel Kindred, the book that transported her from the science fiction ghetto to a more mainstream audience, such as the women who read Essence, that embraced her work. Set in America’s 200th birthday year of 1976, when the airwaves were overflowing with Bicentennial tales of brave white men and the declaration they signed that declared everyone free except Black people, Kindred told the story of a modern day Black writer named Dana Franklin who, on the same day she moved to a new house with her white husband Kevin, literally began being zapped through time into antebellum Maryland, back to the slavery days when it was illegal for Black people to read, let alone write. For some, this was when America was great, for others it was a nightmare that only ended in escape or death.

“One of the books that I read when I was doing Kindred,” Butler told the New York Times in 2000, “was a book called Slavery Defended. It was a wonderful addition to my research, because you don’t read very much about the defenses of slavery these days. And there were a lot of them. One of them said blatantly that it was necessary that the poorest class of white people have someone that they could be better than.”

On Dana’s first jump she saved a drowning boy named Rufus and, minutes after getting the kid to dry ground, had the barrel of a rifle aimed at her face. No doubt the pale faced man holding the gun thought she was a runaway slave, but Dana jumped back into her own era before she could have her head blown off. It soon becomes apparent that saving Rufus again and again from a disastrous end was her mission in order to make sure her own bloodline began.

Afterward, each jump back and forth through time became more brutal and difficult, especially so when her Caucasian husband is also flashed back with her. “Forget the scariness of a dystopian future,” Ytasha Womack wrote in her 2013 book Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture, “the transatlantic slave trade is a reminder of where collective memories don’t want to go, even if the trip is in their imagination. The tragedy that split the nation into warring factions has effects that can be felt in politics of the present.”

Coming two years after the Roots “television event,” a 1977 miniseries based on the book by Playboy interviewer/The Autobiography of Malcolm X collaborator Alex Haley’s text that helped make slavery a part of mass discussion, Kindred was rooted in the fantastic and magical while simultaneously depicting a raw reality. However, Butler didn’t consider it a sci-fi novel.

“If you’re going to write science fiction, that means you’re using science and you’ll need to use it accurately,” Butler told Joshunda Sanders in 2004. “At least speculate in ways that make sense, you know. If you’re not using science, what you’re probably writing is fantasy, I mean if it’s still odd. Some species of fantasy… people tend to think fantasy, oh Tolkien, but Kindred is fantasy because there’s no science. With fantasy, all you have to do is follow the rules that you’ve created.” In 2017, comic book artist John Jennings teamed with writer Damian Duffy on a brilliant graphic novel of Kindred in 2017 that received the 2018 Eisner Award for Best Adaptation from Another Medium.

Octavia Butler followed the rules that she created for herself and her writing. Throughout the 1970s she scrimped, scrapped, sacrificed and submitted her work, and was finally becoming the writer she’d always wanted to be. In 1980, the brilliant Wild Seed was published. This was after achieving literary success with Kindred, a success she’d long wanted not just for personal gain and fame, but to also take care of her mother.

In 1981 Butler began working on a new novel she hoped would be her best seller. Titled Blindsight, she envisioned it as a commercial blockbuster that would on the top of the New York Times bestsellers list. Unfortunately, after much writing, rewriting and two completely different drafts, Butler was never able to sell the book. In the 2017 text Luminescent Threads: Connections to Octavia E. Butler edited by Alexandra Pierce and Mimi Mondal, biographer Canavan wrote in his essay ‘Disrespecting Octavia’ about the shelved project.

“Blindsight is Butler’s lost thriller, a novel more in the mood of Stephen King (whom she admired and envied) than any other works. It tells the story of a boy born blind, but with strange psychic powers, who becomes the leader of a cult-like religious movement.” Though Canavan declared Blindsight a good book, it was sent out to and rejected by a few publishers. Butler abandoned the book in 1984, the same year the bleak Clay’s Ark, the last Patternmaster book written, was published.

For the next few years Butler would plan and plot her Xenogenesis series, with the first book Dawn published in 1987. Into the ‘90s, Butler would have her biggest successes with the publication of Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998). In 1995 she was the recipient of the MacArthur Grant, also called “the genius award,” and received $295,000 that was paid over five years.

In 1999 Butler moved to Seattle, more specifically Lake Forest Park, Washington, where she wrote her the vampire novel Fledging, which was published in 2005. Butler had been dealing with her high blood pressure and the prescribed medicine was making her foggy. Her writing was coming slow, if at all and the third “Parable” book, which she began before Fledging, was stalled. Indeed, it was a long, bumpy road from Pasadena to prosperity, from writing in notebooks at her mother’s kitchen table to sitting behind a typewriter in her own apartment, from collecting rejection slips to composing classic texts, from working as a dishwasher or warehouse cog, waking-up in the middle of the night to write, to being hailed a genius and gifted a couple hundred thousand times in the process.

Butler came into science fiction as the first Black female writer, but her work has inspired a speculative minded sisterhood of scribes that includes Sheree Renée Thomas, Nalo Hopkinson, Nisi Shawl, Ytasha Womack, Walidah Imarisha, adrienne maree brown, Nnedi Okorafor, N. K. Jemisin and legions of others we haven’t heard of yet. In life her influence was strong and, since her untimely death on February 24, 2006, has gotten that much stronger.

Butler died when she fell and hit her head. Other sources claimed it was a stroke that caused her fall, and, in the end, killed her. She was 58. Though her life was short, her legacy roars on. In Butler’s lifetime, she tore down walls and destroyed barriers so that others could have their literary freedom. As N. K. Jemisin wrote in her 2019 introduction to Parable of the Sower reissue “We weren’t asking for much from our fellow writers: just more than European myths in our fantasy, and more than token representation in the future, present, and past.” Somewhere beyond the stars, Octavia Butler was smiling.

___________________________________

Thank you to writer Lynell George for her generous assistance.