“Deportation will not stop the storm from reaching these shores. The storm is within and very soon will leap and crash and annihilate you in blood and fire.”

–American Anarchists pamphlet (1919)

If you go downtown in Manhattan to what used to be the offices of J. P. Morgan & Company, at the corner of Wall and Broad streets, you will find the sculpture called Fearless Girl standing there. She bravely faces the Stock Exchange across the way while at her back, along the wall of the empty former Morgan building, the smooth surface is pocked here and there with small limestone scars.

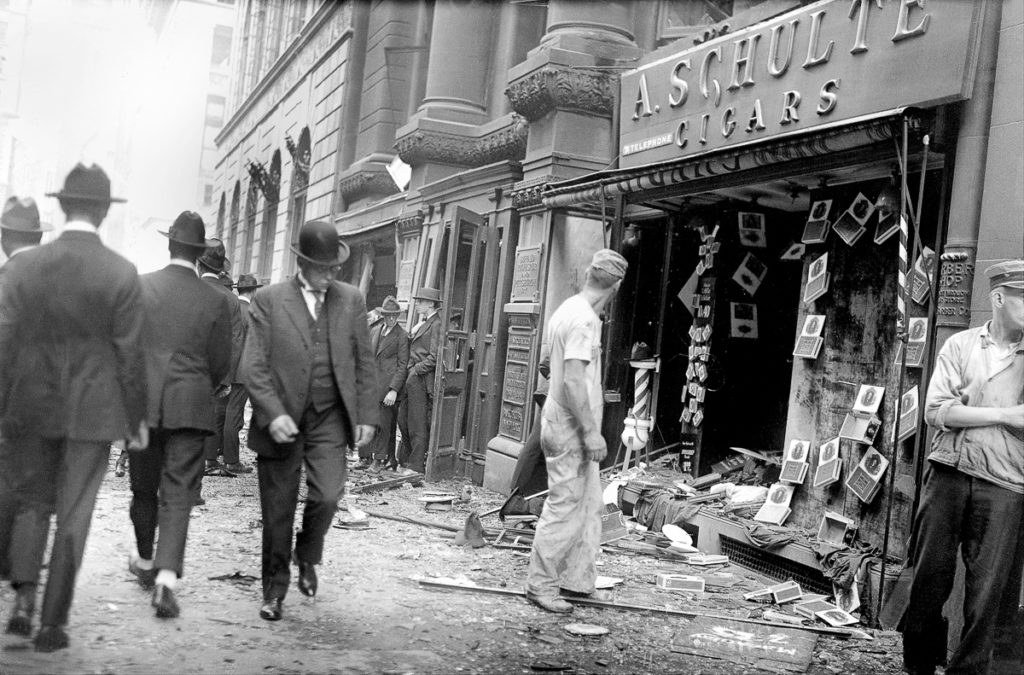

These are in fact scars from the Wall Street bombing of September 16th 1920, which was, until the devastation at Oklahoma City seventy-five years later, the most deadly terrorist attack in American history. The country seemed to recover surprisingly quickly, not having to relive video of the horror dozens of times on cable. The day after the explosion, the Stock Exchange and curbside trading nervously resumed, “[l]ike a strong man who sticks to the line after binding up his wounds and sewing on his wound stripes,” reported the New York Sun. New Yorkers came by the thousands to the bomb scene that day to show their defiance and exorcise their fears. An event honoring “Constitution Day,” the 133rd anniversary of the document’s adoption, had been previously scheduled for that day in the area near the George Washington statue, which was surprisingly undamaged by the blast. The small celebration swelled into one of the largest gatherings in Wall Street’s history. The crowd sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” and listened to speakers defy the nameless radicals responsible for the bomb.

Twenty-four hours before, just after noon on September 16, 1920, a horse cart filled with dynamite and sash weights had exploded in front of the Assay Office, near the intersection of Wall and Broad, killing thirty people instantly and injuring about 300 others. (Eventually, some forty would die.) Across the street, Morgan already had its street level windows caged against the threat of bombs, but these made little difference that day after the wagon lumbered west on its cobbled journey into place.

The lunch hour had barely begun, and many of the victims were messengers crossing the street or clerks hit by shattered glass as they ate at their desks. The hundreds of pounds of sash weights acted like shrapnel. One piece of iron was blown to the thirty-fourth floor of the Equitable building; canopies burned and windows broke a quarter-mile away. “I saw the explosion, a column of smoke shoot up into the air and then saw people dropping all around me, some of them with their clothing afire,” the head of the Stock Exchange’s messengers, Charles P. Dougherty, remembered. The Exchange closed within a minute of the explosion, for fear of the falling glass, which might have seriously injured the hundreds of traders caught inside if it had not been deflected by the building’s big silk curtains. “I first felt, rather than heard the explosion,” an eyewitness reporter for the Associated Press recalled. “I dodged into a convenient doorway to escape falling glass and reach a telephone and call the office. Looking down Wall Street later, I could see…a mushroom-shaped cloud of yellowish green smoke which mounted to the height of more than 100 feet, the smoke being licked by darting tongues of flame.”

Outside, said a visiting coal magnate, glass covered the street like a snowstorm; wounded people and severed body parts lay scattered everywhere. The blast, which witnesses said tossed a nearby automobile 20 feet in the air, also stove in the offices of J. P. Morgan, just across from the bomb cart, decapitating the firm’s young chief clerk, William Joyce, who had been seated near the front. Morgan himself read about the bombing while vacationing in Scotland. “This bomb was not directed at Mr. Morgan or any individual,” said the chief of the Secret Service, William J. Flynn. “In my opinion it was planted in the financial heart of America as a defiance of the American people. I’m convinced a nationwide dynamiting conspiracy exists to wreck the American government and society.” Whether or not the bomb had been aimed at Morgan, the estates of Morgan, Rockefeller, and other prominent men of the Street were now put under guard.

Two charred horse hooves, the only whole pieces of the horse or the wagon, landed at the foot of Trinity Church, into which a number of the wounded struggled, seeking refuge from the fire and acrid smoke. Detectives carried the blackened horseshoes to 4,000 blacksmiths along the Atlantic seaboard but came up only with the recollection of an Elizabeth Street smith, Dominik De Grazia, that he had recently changed a shoe for a “Sicilian”-accented driver. Ten tons of broken glass were carted off to police headquarters, where they were panned for clues and kept for two years.

Aftermath of the Wall Street bombing, 1920.

Aftermath of the Wall Street bombing, 1920.

Then, as now, many Americans held a particular ethnic picture of a terrorist; at that time, it was based on the Italian and Russian radicals credited with bombings over the previous 10 years in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York, Boston, Milwaukee, and Washington. Multiple scenarios for the explosion emerged almost immediately. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer thought the Wall Street attack must also be the work of anarchist or Bolshevik groups, and he quickly arrested the head of the Industrial Workers of the World, Big Bill Haywood, “as a precaution.” A less sinister, and less popular, explanation claimed the horse cart belonged to a dynamite company and had simply gone off upon hitting a cobblestone, but by day’s end the fire department had accounted for all such deliveries. “Authorities were agreed that the devastating blast signaled the long-threatened Red outrages,” the Times reported on its front page the day after, while an adjacent article followed the far weirder story of “Two Cards of Warning” sent by the former ninth-ranked men’s tennis player, Edwin Fischer, who had vaguely predicted the explosion to his friends.

Fischer, a seldom-employed 44-year-old sportsman from the Upper West Side, had picked both September 15 and 16 as likely days for the attack; he had also warned a groundskeeper at his tennis club and a stranger on a train and had told a Toronto bellboy that some millionaires were soon to get what they had coming. His brother-in-law, who caught up with him in Ontario after he had mysteriously fled, reported that Fischer had twice been committed to sanitariums but had nevertheless shown psychic powers for several years. Dr. Walter F. Prince, at the American Institute for Scientific Research, told reporters it was possible Fischer had received a “psychic tip” of the bomb plot, like “picking up a wireless message.”

Fischer, it turned out, was not an admirer of Wall Street and predicted bad things happening there pretty regularly. After he was held at Bellevue Hospital, he also told detectives he was an alchemist, a mind-reader, and, least likely, a sparring partner for Jack Dempsey. They pronounced Fischer harmlessly (if annoyingly) insane and released him.

Other explanations for the bombing included a botched robbery or an attack on the Treasury. On the day of the explosion, $900 million in gold bars was being moved out of the Sub-Treasury Building, which was next door to the new Assay Office, where the deadly wagon was parked. At the time it went off, workmen at the Treasury had just closed the side-entrance doors for lunch, possibly saving themselves as well as the gold.

But the answer to this mystery may have been disappointingly plain. Postal workers found circulars mailed a block away between 11:30 and 11:58 on the fatal day: “Remember/We will not tolerate/any longer/Free the political/prisoners or it will be/sure death for all of you/American Anarchist Fighters.”

The Wall Street bombing was possibly revenge for the murder indictment five days earlier of two Italian-born anarchists in Dedham, Massachusetts…

The Anarchist Fighters had been linked to radical groups (including what newspapers called the notorious “Galliani gang”) around Lynn, Massachusetts, a place federal authorities then considered “the most dangerous spot in America.” The Wall Street bombing was possibly revenge for the murder indictment five days earlier of two Italian-born anarchists in Dedham, Massachusetts, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, followers of the anarchist writer Luigi Galleani.

The most intimate known portrait of the anarchist Luigi Galleani is his Italian mug shot. Taken sometime in the late 1890s, it shows a man in his fierce prime wearing a scraggly goatee above his dark morning coat and uncollared shirt; his eyes darkly appraise the policeman fiddling on the other side of the camera. An enemy of every government he ever encountered, Galleani was born in the Piedmont town of Vercelli in 1861 and discovered the anarchist cause while in law school in nearby Turin. He abandoned his studies to become a man whose inciting words and violent speeches would keep him in motion through much of his first forty years—fleeing prosecution in Italy, chased from France, Switzerland, and returned home, where he was sentenced to an Italian prison island off Sicily, Pantelleria, in 1898. When he landed in New York in October 1901, just months after an anarchist had killed the American president, William McKinley, conditions seemed right in America for his type of revolution.

Luigi Galleani.

Luigi Galleani.

Galleani never bombed anyone himself, but he inspired others to do so through his writings and speeches on direct action, and instructed them in precisely how to fashion their own explosives in a widely circulated pamphlet from 1905. The Galleanists’ objective was to create chaos and provoke an overwhelming response that would speed up the apocalyptic reckoning of the system they despised. As a character says in Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent (1907), ‘You anarchists should make it clear that you are perfectly determined to make a clean sweep of the whole social creation.’

During San Francisco’s Preparedness Day parade on July 22, 1916, a suitcase bomb went off, killing ten people and wounding forty others. Two labor leaders, Tom Mooney and Warren Billings, were separately convicted for the crime but later pardoned, while subsequent history suggests another suspect, Galleanist expert bomber Mario Buda, who probably also engineered the Wall Street attack three years later. As the United States moved toward entering the war in Europe Galleani advised his readers to resist the draft by traveling to Mexico and studying anarchist techniques. In fact, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti actually met at such a camp in Mexico in 1917. Galleanists managed to explode a black powder bomb that killed ten people inside a Milwaukee police station in late 1917. In April 1919, they mailed some 36 bombs in Gimbels boxes addressed to a high-profile group that ranged from Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis to J.P. Morgan, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Commissioner of Immigration Anthony Caminetti and the new Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. Months later, they tried to kill Palmer again.

On June 2, 1919, Carlo Valdinocci, the former editor of the Galleanist newspaper Cronaca Sovversiva, was blown up in Georgetown as he attempted to place a deadly package at the Palmers’ door. The family had just retired moments before from the house’s downstairs library when Palmer heard a surprising thud against the front door—perhaps the bomber tripping on the steps—followed by the explosion that rocked his home. “The morning after my house was blown up,” Palmer recalled, “I stood in the middle of the wreckage of my library with congressmen and senators, and without a dissenting voice they called upon me in strong terms to exercise all the power that was possible…to run to earth the criminals who were behind that kind of outrage.” What followed was a series of increasingly broad and brutal roundups of immigrants and suspected radical organizations, the infamous ‘Palmer Raids,’ launched by his Justice Department in 1919-1920. Palmer’s pursuit of radicals included round-ups of thousands who merely sounded foreign, leading to the formation of the ACLU in January 1920. With President Wilson incapacitated by a stroke, a drawn-out public debate over the raids grew between Palmer and the acting Secretary of Labor Louis C. Post, who challenged Palmer’s warrants and nullified 2000 of his deportations.

Palmer house in Georgetown following bombing.

Palmer house in Georgetown following bombing.

Three weeks after the Palmers’ house was bombed, Luigi Galleani and eight of his followers were deported. After his return to Italy, Galleani did not take to Benito Mussolini, who came to power in 1922. After serving another term on a prison island, Galleani died of a heart attack while living under house arrest in 1931. The following year, Galleanists blew up the home of the deciding judge in the Sacco-Vanzetti trial, Webster Thayer, who survived but lived the rest of his life at his club.

“If the Wall Street bomb explosion was the result of a murder plot…it speaks eloquently for the bond of silence which the lawless world imposes on its members.”

“If the Wall Street bomb explosion was the result of a murder plot,” Sidney Sutherland wrote in Liberty magazine nine years afterward, “it speaks eloquently for the bond of silence which the lawless world imposes on its members.” The anarchist bomber Mario Buda escaped and returned stealthily to Italy, photographed in later years with a mysterious severed finger on one hand, as if from a bomb accident. After Buda died in Italy in 1946, friends found a cache of dynamite beneath the old man’s stoop.

The Wall Street bombing struck at the powerful and killed the ordinary, with many close calls in between: Young Joseph P. Kennedy was knocked to the pavement while on his way to a downtown lunch appointment; walking at a slightly faster clip would have deprived two of his sons of his bullying aspirations for them to become President, and his third and fourth, Robert and Ted, would not have been born. A young clerk at the National City Bank, F. Marvin Carpenter, after being tortured for five days by what he had seen the day of the explosion, chose to climb to the roof of his bank and jumped seven stories down into the afternoon crowds of Exchange Place.

One Wall Street messenger, fifteen-year-old Cornelius Brosnan, was knocked several feet from where he stood in front of the Morgan building that day but survived, reporting the force of the blast had removed the Christ from his cross on the crucifix he kept in his pocket. Another boy, Saverio Guliano had been on his way to an interview with a Wall Street bank when the explosion came. He lived but wandered in shock for more than 12 hours after the blast, finally arriving home at 1:00 in the morning, when his relieved mother Palma asked him what had happened. He “could give no account of himself,” said a newspaper. He simply shook, unable to eat or even speak. Where would he begin.

___________________________________

Nathan Ward’s novel of the Wall Street bombing, Ashes of My Youth, is forthcoming this fall as an Amazon Kindle. His last book, The Lost Detective: Becoming Dashiell Hammett, was nominated for the Edgar and Anthony mystery prizes. His next (from Grove Press) is Ulysses of the Wild West: To the End of the West &The Birth of Hollywood with the Cowboy Detective Charlie Siringo.