The conflict in Vietnam cast a long shadow over pulp and popular fiction in the late 1960s and the 1970s. Vietnam veterans were hunted by small-town redneck police in David Morrell’s 1972 novel, First Blood, dealt drugs in Vern E. Smith’s The Jones Men, and staged an abortive bank heist in Dog Day Afternoon, both published in 1974. In the Lone Wolf series, New York ex-cop and Vietnam veteran Burt Wulff mounted a fourteen-book battle from 1973 to 1975 against the drug dealing criminal organization, “the network,” in which he treated the streets of America’s major cities as an extension of jungles of Southeast Asia.

Vietnam was the training ground for many of the characters that populated men’s adventure and crime pulp in the 1970s. These included Remo Williams, a.k.a. “The Destroyer”; Mark Hardin, a.k.a. “The Penetrator”; Mack Bolan in Don Pendleton’s long-running series, The Executioner; Joseph Greene’s suave trouble shooting PI, Superspade; and Joe Nazel’s Harlem native Henry Highland West, referred to as “The Iceman.” Johnny Rocetti used his skills acquired as a Green Beret in Vietnam to take on the Mafia in Frank Scarpetta’s blood-drenched Marksman series. Jim Rainey, the central character in the Soldier of Fortune series, learned his craft working for the American government’s “Phoenix Group” in Vietnam, no doubt a fictional take on the real-life CIA-directed covert assassination program, the Phoenix Program. And the Mind Masters series by John F. Rossman and Ian Ross depicted a character called Britte St. Vincent, a top-secret U.S. government agent whose special psychic powers were activated by the horrors he experienced in Vietnam. More broadly, Vietnam’s traumatic impact on American society would become a cypher through which pulp and popular fiction namechecked cultural fragmentation, growing disillusionment with the American dream, dishonest and unaccountable government and corporations, and the power of the military-industrial complex.

But while Vietnam equipped numerous fictional characters with the skills to combat the Mafia, terrorists or various other threats, few books in the late 1960s and ’70s focused on the war and its consequences as anything more than a background or reason for why a character was as confused/damaged/homicidal as they were. Removing reportage and autobiographies, fewer still were actually set in Vietnam. Given the lengthy U.S. involvement in the war—the first major deployment of combat troops took place in May 1965—and pulp’s time-proven ability to riff off the latest prominent issues or newspaper headlines, we can only speculate as to why writers and publishers were loath to sensationalize the conflict with the enthusiasm they did with everything else. Was it a case of self-censorship? Or was the conflict simply too close to the bone, given the deep divisions over the war in West that grew as the conflict dragged on?

More likely, the answer involves sales or, more to the point, the lack of them generated by stories that focused on Vietnam. Vietnam stories “were absolute poison,” recalls Mario Puzo in an interview in the 2012 book Weasels Ripped My Flesh! Two-Fisted Stories from Men’s Adventure Magazines of the 1950s, ’60s & ’70s. Puzo, who penned numerous war and crime stories for men’s magazines in addition to his more famous work such as his 1969 novel The Godfather, says: “They [readers] hated it [Vietnam]. Also, we weren’t the heroes. Just like the Korean War—we used to call that The No Fun War. World War II was The Fun War. And you could get some mileage out of the Civil War and World War I. World War II was a Bonanza. But Korea and Vietnam were losers.”

A similar dynamic appeared to have been at play in film. Among the first films to directly tackle the war was The Green Berets (1968), a jingoistic and bombastic war film developed by John Wayne with the express intent of influencing U.S. public opinion in favor of the war. In the years that followed, few mainstream films expressly dealt with the Vietnam War until the release of Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter in 1978 and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now in 1979.

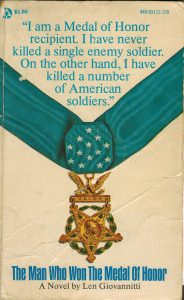

Two early pulp books that break with the reluctance to examine America’s Vietnam War experience in detail are Con Sellers’s Where Have All the Soldiers Gone? (1969) and The Man Who Won the Medal of Honor by Len Giovannitti, published in 1973.

The main character in Where Have All the Soldiers Gone? is antiwar activist Lee Boyd, who decides that he will have more impact by joining the marines and exposing what is going on from the inside. The book opens with him in Vietnam, dealing with the hostile intentions of the enemy and his hard-charging, right-wing, college-student-hating, career-soldier superior, Sergeant Garrick. Boyd’s efforts to stay alive are interspersed with passages in which he reminisces about his life back in San Francisco, “the City,” as he refers to it, and his girlfriend, Lisa, who he fears is drifting apart from him. “She was getting mixed in with the other wild, swinging chicks in Monterey and the City and points around and between.”

Boyd tells anyone who will listen about the antiwar movement and how wonderful life is in San Francisco:

“. . . the creatively intellectual atmosphere of Haight-Ashbury where everyone used the mind-expanding, senses- expanding stuff, and found themselves reveling in the new knowledge, the new and strong importance of putting together a society completely apart from the phony values of the present one. It was bathing in the sounds from the different folk-rock groups as color wheels spun lazy. . . . It was swaying together, holding hands with the everywhere flowers and chanting Hell no, we won’t go, answering the thickbeard speaker who thundered all these irrefutable truths from the platform. . . . What else was it? Freedom, man—real freedom for the first time anywhere. . . . It was freedom to listen to Ginsberg and block the induction center and tell the fuzz to kiss off, and what the hell could they do about it.”

Though it had been a big deal in the States when he announced he was joining up, Boyd’s plan to spill the beans on what is going in Vietnam—the misuse of authority, the unauthorized deaths of civilians, the poverty of the locals—is frustrated because the media are no longer interested. He has been forgotten. His fellow American soldiers either couldn’t care less or consider him an oddity. Most just want to do their tour, survive and get back home. He is particularly disheartened that the increasingly radicalized black marines don’t consider him a fellow revolutionary. To them, he’s just whitey and a weirdo. “You think Charlie and me are the same color? You think Charlie hasn’t got a word that means nigger in his language?” a black soldier asks him, possibly riffing on and upending Muhammad Ali’s iconic statement, “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong. No Vietcong ever called me nigger.”

Boyd witnesses numerous atrocities by American forces, including a young Vietnamese girl killed by a fragmentation grenade thrown by Garrick and a village shot up by a psychopathic marine called Whiney, in retaliation for a bomb attack on the local village bar frequented by off-duty Americans. Boyd protests these acts to the military authorities higher up, but they do nothing. His only respite is a local prostitute, Mai. A “small fury, miniature tigress” in bed, she is a thinly drawn character who, when she does speak, communicates only in broken English.

The author’s agenda becomes clear about halfway through Where Have All the Soldiers Gone?. Realizing he is a good medic, Boyd starts to take pride in his work. This eases tensions with Garrick, who in turn reveals himself to the young marine as a self-made scholar who can discuss the relative nature of poverty and why America is at war. He gets Boyd to slowly change his antiwar views and becomes something of a father figure to him. Parallel with this, Sellers ups the ante in terms of the horrific acts committed by the Viet Cong on American soldiers. There are graphic punji stick injuries, and the Americans discover a dead member of their platoon skinned alive by the enemy. Boyd’s final metamorphosis occurs when Garrick is killed trying to rescue a wounded marine. When journalists eventually find him and ask him for the low down about what is happening in Vietnam, he refuses to talk to them. Then he applies for a transfer to become a fighting marine.

This none too latent Pax Americana aside, this book is well written and deserves kudos for at least attempting to tackle the war itself directly. That Sellers was no peacenik is evident from the brief biography in a February 3, 1992, obituary in the Lewiston Tribune. He served seventeen years in the army, was wounded twice as an infantryman during World War II, and was decorated with Silver and Bronze stars and a Purple Heart. He served as an army combat correspondent in Korea but was supposedly discharged in 1956 for alcoholism. He turned to writing stories for men’s pulp magazines and wrote some 230 novels under ninety-four names, everything from science fiction to spy novels, westerns, movie tie-ins, and smut.

The Man Who Won the Medal of Honor is a far more radical take on the in-country experience of American troops in Vietnam. The author, Len Giovannitti, was another World War II veteran, serving in the Army Air Corps as a navigator. His New York Times obituary states that on his fiftieth mission, his plane was shot down in Austria, and he was held prisoner for a year. He told of this experience in his first novel, The Prisoners of Combine D (1957). He was also an award-winning television writer and filmmaker who made hard-hitting stories about social issues such as the energy crisis, racial tension, and juvenile delinquency. His Vietnam novel begins with the protagonist, eighteen-year-old private David Glass, recounting the events that saw him mistakenly awarded the Medal of Honor, America’s most prestigious military decoration, while waiting in jail on death row. As the pull quote on the front cover says, “I am a medal of honor recipient. I have never killed a single enemy soldier. On the other hand, I have killed a number of American soldiers.”

An orphan who joined the army to escape the institution he grew up in, Glass shows little aptitude for military life except for being an excellent marksman. Stationed in central Vietnam in the summer of 1968, his first encounter with “Charlie,” the most common slang term for the Vietnamese, is a young boy who the marines discover on a routine sweep of a village, and who his tough, uncompromising commander, Sergeant Stone, is convinced is a spy. After pumping the boy for whatever information he has, Stone slits his throat. Glass reports him, but in much the same way as Boyd is ignored in Sellers’s book, the military command is unconcerned by what is obviously just one more civilian death among so many. They also view Glass’s attempts to bypass the chain of command as a threat to military harmony and discipline. At this point, Glass resolves “not to kill any Vietnamese except to save my own life.”

He takes a further step when he kills a marine he suspects has murdered a Vietnamese civilian on a night patrol. Transferred to the role of a door gunner on a chopper in the Mekong Delta, his vigilante-style actions culminate on a routine reconnaissance mission with a ruthless George Patton–style Brigadier General George Rusty Gunn. Gunn shoots three “gooks” working in a field with a machine gun out of frustration because they have not encountered the enemy.

“You know something?” Gunn tells Glass, “Killing gooks gives me a hard on.” At which point Glass pushes Gunn and the colonel accompanying him out of the helicopter. The deaths are covered up by the military.

Glass completes his tour of duty and, through some sort of accident, is awarded the Medal of Honor. He wants to turn the awards ceremony into an antiwar protest, but instead it becomes a fumbling and uncertain attempted assassination of the president. The book concludes with the possibility that Glass is insane, although whether he was always like this or was made this way by his experiences in Vietnam is unclear.

The Man Who Won the Medal of Honor is full of passages detailing the horror and futility of the war, particularly the more often than not one-sided, high-tech carnage inflicted on the Vietnamese. There is so much killing that Glass’s acts of vigilante justice can easily be concealed amid the chaos. Also writ large is the farcical nature of Washington’s strategy of trying to win the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese while destroying their country. Interestingly, it must also be one of the first novels to deal with the practice of “fragging.” As military morale collapsed, soldiers increasingly moved from refusing orders to deliberately wounding or killing those who issued them, as well as other unpopular combatants, often through the use of fragmentation grenades. Estimates of the number of incidents vary, with some putting them as high as one thousand attacks and at least fifty-seven deaths. Giovannitti also namechecks a number of other key aspects associated with America’s Vietnam experience: drug use, the racial divide between black and white troops, the total alienation of the Americans from the Vietnamese, the division between those who revel in the war and those whose only aim, in Glass’s words, is to get through “a nightmare that measured 365 days—and when it ended we would go home and resume our lives as if it had never happened.”

At least one critic branded the book as sensationalist and criticized the character of Glass for “committing the same crimes with the same rationalizations that the army used to explain its actions in this mess: killing is OK as long as you’re on the right side, wherever that happens to be.” Another take on The Man Who Won the Medal of Honor is that it speaks to the radical energy of the times, when a small but significant section of the U.S. population not only openly disagreed with America’s mission in Vietnam but sup- ported the enemy.

The book can also be viewed as a meditation on the trauma of war, a reading that similarly applies to the much-better-known text, Tim O’Brien’s 1978 novel, Going after Cacciato. Labeled by the author, himself a Vietnam veteran, a “peace novel” rather than an antiwar book, it won the National Book Award. It has been dealt with extensively elsewhere, so I will not devote too much space to it here. It tells of the events that ensue after a soldier called Cacciato goes AWOL from his unit in Vietnam and seven soldiers led by Paul Berlin go after him, tracking him to France and through Asia. Cacciato, a Forrest Gump–type character, leaves evidence of his passing along the way, such as equipment and bits of a map. The book has an almost magical realist quality, interspersed with combat and Berlin’s thoughts on Vietnam, suggesting that the entire story might be a fantasy, Berlin’s mechanism for coping with the horror of the war.

Plots by militant black liberation groups to destroy major infrastructure or assassinate political figures so as to inspire black insurrection were a common preoccupation of late 1960s and early 1970s pulp fiction. Operation Burning Candle (1974), written by black academic and writer Blyden Jackson, takes this trope and infuses it with a Vietnam War plotline. Disillusioned by the Nixon presidency and having watched every major black leader who offered hope get killed or jailed, black psychology student Aaron Rogers enlists to fight in Vietnam. The move is a cover for his plan to put together a group of black men, all Green Berets like him who have cut their teeth working covert special ops behind enemy lines, and who have each passed the initiation ceremony of fragging a white officer. They switch identities with soldiers killed in action, return to the U.S. and congregate in New York, where, as part of a much larger force, they aim to put into effect Operation Burning Candle. Mass transit shutdowns and power blackouts across Manhattan are intended as a prelude to assassinating the most trenchant racists in the U.S. Senate at the upcoming Democratic National Convention in Madison Square Garden.

The story shifts between multiple points of view in addition to that of Rogers: members of Rogers’s family in Harlem, including his broken, alcoholic, but still politically radical father, none of whom know Rogers is alive; virulently racist southern “Dixiecrat” Senator Josiah Brace, who is trying to sabotage the nomination of a liberal candidate at the convention so he can take the top slot himself; and Dan Roberts, a police officer and Korean War vet who is investigating the disappearance of an undercover police operative planted in a street gang known as the Black Warriors, killed by Rogers as a potentially weak link in his plan. Roberts connects the death to a series of well-organized bank robberies that, unbeknownst to him, are being staged to fund Operation Burning Candle. The idea of planting police agents in black organizations is a direct reference to the FBI’s infamous COINTELPRO operations, aimed at infiltrating, spying on, disrupting, and ultimately breaking up organizations viewed by the authorities as subversive. These included antiwar and civil rights groups and the Black Power movement. Roberts is a racist, who considers Harlem enemy territory. “You’ve been in the streets of Harlem day and night for the last three years,” a senior policeman tells him at one point. “You read the papers—Chicago, Detroit, Newark, Cleveland. There’s another kind of war shaping up, Dan. It’s that war that we mustn’t let happen.” Each of those cities experienced major race riots and ghetto uprisings between 1964 and 1967.

Operation Burning Candle is a well written, compelling thriller, in which Rogers’s attempts to bring his plan to fruition run parallel with the dawning awareness on the part of the police that something major is going down, their efforts to discover what it is and prevent it. The story is also a sophisticated political statement that feels alarmingly relevant today. Particularly interesting are the passages elaborating on Rogers’s plan, his contention that only through “cleansing violence” can the cycle of black oppression and its dehumanizing impact on white America be broken. As part of this, the novel specially mentions the influence on Rogers of the work of Frantz Fanon and Malcolm X about the use of targeted violence to galvanize the black people into action. In one key scene, when the insurrectionaries seize a radio station, Rogers makes a lengthy broadcast about the group’s aims.

“Brothers and sisters.” Aaron went on, more urgently now, “this weekend, in the next 72 hours, brothers and sisters, we are going to find that unity! Our unity as black people, as brothers and sisters. . . . We are going to end four centuries of separation from each other. We shall no longer be alone, dying, crying, by ourselves, unable to reach out to each other—unable to touch the black hand so close to our own, out- stretched in anguish! An end to that, brothers and sisters! In the next 72 hours! We are going to establish our own humanity and force them to act as humans too!”

He asks everyone who supports the uprising to put a lighted candle in their window “so that we know your home is our home.” Not only do candles proliferate but mass spontaneous rallies break out across the country. Toward the end of the book, thousands of black Americans watch guerrillas assassinate twelve senators live on prime-time television, shouting joyfully, “They’re killing the honkies!”

The one blind spot of Operation Burning Candle’s otherwise sharp politics are the scenes set in Vietnam. While Jackson depicts the racism in the U.S. military, Rogers and his men seem largely uncritical of the destruction of which they are a part of in Southeast Asia. They formulate their plan in “Soulville,” a slum in Saigon where black GIs go on R&R, largely off limits to whites, where they sleep with local women, impoverished by the war, and bond in a gun battle against racist military police.

Another key trope about the Vietnam War explored by pulp and popular fiction in the early 1970, was the returned soldier, damaged, sometimes irrevocably, by experience of the war, who has difficulty readjusting to a country that had changed while he had been over-seas. One example is Newton Thornburg’s excellent 1976 noir novel Cutter and Bone, about an embittered Vietnam veteran who becomes so obsessed with the possibility that his gigolo friend Bone has witnessed a murder that he tries to find the culprit. Another fictional examination is the 1979 novel Coming Home by George Davis, who joined the U.S. Air Force in 1961 and flew numerous missions in Vietnam. This is not to be confused with Hal Ashby’s 1978 movie in which a woman (Jane Fonda) whose husband (Bruce Dern) is in Vietnam falls into a relationship with a veteran (Jon Voight) crippled in the war.

One of the hardest-hitting takes on the domestic blowback of the war is Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers. First published in hardback by Houghton Mifflin in 1974, it enjoyed a double life as a paperback, as the cover for the 1976 version by downmarket UK publisher Star Books demonstrates. The book was also made into the underappreciated 1978 film Who’ll Stop the Rain.

John Converse is a freelance journalist covering the conflict in Vietnam. The reasons why he chose to go are unclear. “He hopes something worthwhile might emerge from such an expedition, there might be a book or a play.” But Stone hints the journey is just as much about a search for meaning and an escape from his life in the States, including a child and an unhappy union with his wife, Marge. In Saigon he finds writing work and falls in with a crowd of “dope people.” Politically liberal, he quickly grows weary with the war, spending most of his time stoned and hanging out in the bars on Saigon’s Tu Do Street. After eighteen months in country and “for all the discoveries, it had become apparent that there would be no book, no play. It seemed necessary that there be something.” That something is a drug deal.

The decision to import three kilograms of heroin is motivated by money but also disgust about America’s actions in the war. The final straw is “the Great Elephant Zap of the previous year,” when U.S. Army Command decided elephants “were enemy agents because the NVA used them to carry things, and there had ensued a scene worthy of the Ramayana,” in which helicopters are sent to hunt elephants all over the south. Whether this occurred in real life or not is unclear, but as Converse tells it, the move produced “a feeling that there were no limits. And as for dope, Converse thought, and addicts—if the world is going to contain elephants pursued by flying men, people are just naturally going to want to get high.”

Converse enlists an old friend, Hicks, a Nietzsche-reading, paranoid former marine now working as a merchant sailor, to traffic the dope to America and bring it to his wife in Berkeley. Overcoming his concerns about the “bad karma” associated with the deal, Hicks smuggles the drugs to the U.S. and brings them to Marge only to discover that corrupt drug enforcement agents have got wind of the deal and are waiting for him. Escaping with Marge, they dump her child with a relative and try and sell the drugs while evading the narcs.

Marge, whom Hicks is soon sleeping with, is an extremely unreliable partner as loneliness and ennui have led her to develop an addiction to the opiate Dilaudid. Meanwhile, Converse returns home to finds his wife and kid gone, and in their place is Antheil, the head narc, who threatens to turn over the journalist to the various illegal interests his heroin deal has threatened unless he helps track Marge and Hicks down.

One of the many strengths of Dog Soldiers is its depiction of the American civilians who flooded into South Vietnam during the war, an aspect of the conflict rarely explored in fiction, certainly not as early as 1974. Stone told the author of Vietnam, We’ve All Been There: Interviews with American Writers (1992) that he drew on his own experience as a correspondent in Saigon in the early 1970s for Dog Soldiers.

“Nineteen seventy-one was probably the baroque period of Saigon. You could run into anybody on the streets of Saigon. There was a whole anti-war contingent of people. Saigon was just full of Americans and Europeans of any possible description. It was a real carnival. There were lots of people with marginal accreditations: stringers from quasi papers, people with forged accredita- tion letters that they had written for themselves. A lot of people were dealing dope. There were a lot of marginal people around, a lot of people only nominally press. There were reporters who allegedly dealt with the black market. There certainly were such reporters who dabbled in gold or cinnamon or dope.”

While the Vietnam section of the novel is over after a hundred pages, the shockwaves of the war infuse everything that follows. Particularly evocative is Stone’s portrayal of the conclusion of the Summer of Love, and the self-interest, paranoia, and disillusionment that followed. This shift was described by Stone as “the time of the dying dream of the sixties in California and also the dying dream of the Great Society—all sorts of bills were coming up due for payment in the early seventies.” This is illustrated in Dog Soldiers through journey undertaken by Hicks and Marge, during which they encounter various refugees from the sixties, including a drug-dealing Hollywood moviemaker and middle-class swingers interested in turning on, before ending up at a semi-abandoned commune in the middle of the desert for the final showdown with Atheil.

While the exact bureaucratic affiliation of Antheil and his men is never directly revealed, their vulture-like pursuit of Converse’s hapless drug deal personifies another major aspect of the domestic and international blowback from the Indochina conflict, America’s involvement in drug trafficking. Alfred McCoy’s seminal 1972 book The Politics of Heroin in South East Asia was the first authoritative work to document Washington’s direct complicity in the drug trade, particularly during America’s “secret war” in Laos. There the CIA used its covert airline, Air America, to transport opium cultivated by anticommunist Hmong tribesmen in return for their loyalty against the communist Pathet Lao, with the organization in turn ploughing profits from the drug trade back into the conflict. McCoy also revealed that the United States was, at best, turning a blind eye to the processing of opium into heroin in jungle laboratories in Thailand. The supply of cheap drugs was one of the facts linked to the poor morale of American troops in the later stages of the war, with some estimating that as many as 15 percent of enlisted U.S. troops were heroin users.

The United Kingdom did not officially become involved in Vietnam, although British troops did provide some training early on to South Vietnamese forces and its special forces were active in a covert role. Australia had been unofficially involved, sending military equipment and advisors to South Vietnam since the early 1960s. This become official when the first Australian ground troops were dispatched in April 1965. Long-serving conservative prime minister Robert Menzies saw the war as part of a broader Communist push into Asia, which, if unchecked, could threaten Australia. Public sentiment was broadly in favor of Australia’s involvement until around 1969, when organized opposition to the conflict and the conscription of young men to fight in it became a mass movement. Australia’s military participation in Vietnam ended in January 1973, when the newly elected reformist Labor government pulled Australian troops out. Approximately sixty thousand Australian troops served in Vietnam, of whom over five hundred were killed and three thousand wounded.

Australian pulp publishers displayed the same reticence to tackle Vietnam as those in the United States. They focused the bulk of their war titles on often-lurid tales of Australian heroism and suffering during World War II, restricting their Vietnam related offerings to the occasional medical romance or spy thriller. That said, several popular novels on the war by Australian authors appeared in the 1960s and early 1970s, including John Rowe’s Count Your Dead (1968), Wake in Fright author Kenneth Cook’s The Wine God’s Anger (1968), and Rhys Pollard’s The Cream Machine (1972).

Rowe, whose military service included a stint in Vietnam, wrote his novel while serving in Washington with the Defense Intelligence Agency. His account of the fortunes of an American officer who finds himself politically at odds with a combat officer about the U.S. involvement in the war, while broadly antiwar, is more about the American experience in Vietnam than that of Australians. The almost impossible to procure book The Wine God’s Anger concerns an army volunteer who becomes disillusioned with the fight against communism and deserts to Bangkok, where virtually the entire book is set. The Cream Machine covers similar ground to Where Have All the Soldiers Gone? in its depiction of a reluctant draftee sent to fight in Vietnam, who slowly comes to appreciate the talents and dedication of the Australian army soldier.

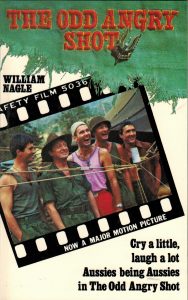

The most famous novel about Australia’s Vietnam experience is William Nagle’s The Odd Angry Shot (1975), made into a movie of the same name in 1979. Nagle joined the army after he left school, trained as a cook and was deployed to Saigon with the Special Air Service (SAS) in 1966. He was later transferred on disciplinary grounds to the infantry in Australia and was discharged at his own request in 1968. He supposedly wrote the first draft of The Odd Angry Shot in one sitting, working around the clock for six days. The story of a group of SAS troops, from their departure to Vietnam to their time in “the scrub” and concluding with their unceremonious return home, The Odd Angry Shot is an antiwar book in the sense that it depicts the futil- ity of the conflict and the alienation of the men who went to Vietnam fight it. The soldiers, including the narrator, start off as believers, keen to do their duty and fight communism: “My rifle feels good as it rests on my lap, oiled and shiny. Twenty-eight rounds of keep Australia free from sin and yellow bastards.” But this sentiment quickly fades in the face of dangerous but largely pointless patrols interspersed by large periods of boredom. At times, the book tries to affect a Catch-22 vibe, but this is undermined by its sullen tone and a depiction of Australian “mateship” that often tips over into racism and sexism, the latter focused on the women the troops have left behind who fail to remain loyal. The book evinces little sympathy for those pro- testing the war back home, who are depicted as having sold out the troops.

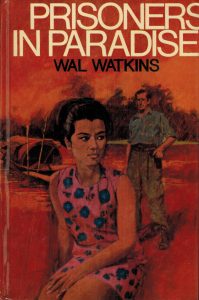

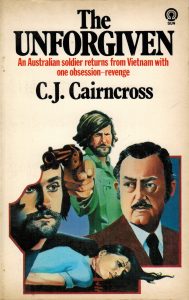

Three other Australian takes on Vietnam from the late 1960s and the 1970s worthy of brief mention are Wal Watkins’s Prisoners in Paradise, first published in 1968 and rereleased with a racy cover in 1972 by Gold Star Publications, and two crime tales, The Unforgiven (1978) and Death by Demonstration (1970).

Nelson, the main character in Prisoners in Paradise, is a sickly schoolteacher involved in the antiwar movement, who is advised by his doctor to give up his political activities because they are bad for his health. His best years behind him and with a disintegrating marriage to a cheating wife, he packs in his Australian life and heads to Bangkok on a voyage of self-discovery. There he falls in love with a young Thai girl, Nan, who claims she is not a prostitute but sleeps with him in return for being kept. Nelson gradually discovers both sides of the escalating conflict in nearby Vietnam have an interest in Nan. The Americans, in the form of a calculating U.S. Army intelligence officer, Murchison, believe Nan is the mistress of the leader of Thai communists who are linked to the Viet Cong. The Viet Cong meanwhile want her for the intelligence she may have gathered during a sexual liaison she had with a visiting senior figure in the South Vietnamese government. Nelson hatches a plan to get the two of them to safety in Malaya but can’t shake the suspicion that the communists are potentially using him as a dupe.

While Prisoners of Paradise comes across a bit like a cut-price The Quiet American, it nonetheless touches on one of the major impacts of Australian involvement in Vietnam: the way it opened up the up the country’s until then parochial culture to greater influence from Asia. Watkins also shoehorns in observations about politics and the war via the discussions that take place between the expatriates who congregate in the Bangkok hotel where Nelson is staying. Like the expat denizens of Saigon in Dog Soldiers, this group live a precarious, hand-to-mouth existence. The only thing they have in common is the creeping awareness that whatever way the Vietnam War goes, they are witnessing the end of Western superiority in Asia.

No detail is available about C.J. Cairncross, the author of The Unforgiven. The novel opens with two men sitting in a car across the street from a gun store, one of them having flashbacks to his time as a soldier in Vietnam. A bomb goes off in the shop and the men steal a number of high-powered weapons. A gun battle ensues between the men and the cops, in which a police officer is injured. One of several bombs that have gone off around Sydney, a criminal informant or “phiz” tells police officer Edward Frazer that they are the work of a couple of professionals from Melbourne: “the Yugos or Arabs or one of that lot.” But further investigation reveals that the stolen guns were part of a consignment for a mysterious gun collector, the high- powered, right-wing businessman/industrialist Carl Hackett. Frazer becomes convinced the bombings have something to do with Hackett’s son, Michael. An anti–Vietnam War protester and conscientious objector at university, Michael was strongarmed by his father into joining the army and going to Vietnam, where he had a complete breakdown and was discharged as medically unfit. He spent time in hospital in Australia before leaving for Canada. Intersecting with the bombing investigation is the discovery of the body of a young female sex worker in a dingy hotel room in Sydney’s vice district, Kings Cross. One of the cops who discover the body, formerly a military police officer in Vietnam, believes the murder has similarities to one that took place in Saigon during the war.

As the story develops it becomes clear Hackett’s son is indeed back in Sydney and has teamed up with another Vietnam veteran, Arch Morley—who may have something to do with the murders—wants revenge on his father. Although The Unforgiven is an average crime novel, it must rank among the first popular Australian novels to fictionalize what was at the time the unnamed and unexplored issue of post-traumatic stress disorder affecting soldiers returning from Vietnam. Some would come to argue this was a particularly pronounced problem for Vietnam vets due to factors such as the guerrilla nature of the war, which resulted in a lack of definition about where the conflict started and ended, the use of defoliants, controversy about the war back home, the young age of those who fought—the average age of Australian servicemen in Vietnam was twenty—and the war being widely viewed as a defeat. As Cairncross writes at one point about Michael and his partner, they “were part of a world that no longer existed, a world where the sun shone and people laughed and fell in love and had babies. That world had been murdered in Asia. Michael had seen it die.”

Death by Demonstration was the last novel of Sydney crime writer Patricia Carlon, a recluse who, it was discovered only after her death, had been profoundly deaf since the age of eleven. Death by Demonstration sees private detective Jefferson Shield drawn into investigating the murder of a young female protestor, Robyn Calder, at an anti-conscription demonstration in Sydney. The police and the university where the demonstrators are studying want to pin the killing on the protest’s organizers. A middle-aged, middle-class white man and veteran of World War II, Shields is no fan of the young, modish antiwar students whose world he has to penetrate in order to uncover the true story behind the woman’s death.

The organizers appear to have made every effort to ensure the demonstration in question was peaceful. But contradicting their story, a photograph surfaces that shows Robyn acting aggressively and brandishing what appears to be an iron bar. One avenue of Shields’s investigation is the so-called Thought Club, a left-wing organization run by a couple of arrogant Saul Alinsky–style professional demonstrators, who help organize radical protests in return for money. There is also some speculation that the demonstration and others like it could be being used as cover by criminals for various robberies occurring in their vicinity at the same time.

Death by Demonstration has a strange, almost featureless setting, probably because all of Carlon’s books were published in the UK, so she may have been keen not to burden British readers with too much Sydney detail. The book does work in depicting what must have been the alarm many experienced at the upsurge in militant youth protest against Vietnam, part of much broader social change sweeping Australian as the country entered the 1970s. Where the book falls down is Carlon’s reliance on slabs of exposition, which comes off as preachy and bogs the story down, as well as the injection of the author’s only thinly veiled politi- cal bias against those protesting the war.

In the late 1970s and the ’80s, men’s adventure pulp characters would travel back to Vietnam on missions to eliminate evil drug lords or, as in the case of Stephen Mertz’s Stone M.I.A. Hunter series, to locate and rescue U.S. servicemen allegedly left behind after the war to languish in various communist hell hole prisons. The one perspective that would not be dealt with in any of the pulp and popular fiction from the late 1960s to the early ’80s was that of the Vietnamese, both North and South, combatants and civilians. It would not be until much later for Western audiences that “Charlie” would acquire a face and get to write their own story.

*

Excerpted from Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980. All rights reserved. Courtesy of PM Press.