In the fall of 2016, Kim Kardashian was robbed in her Paris hotel room by a group of armed gunmen disguised as police officers, who tied her up and relieved her of several millions of dollars worth of jewelry. The story made front page news, coming as it did with the salacious whiff of celebrity spectacle. But the part that interested me the most was how the robbers had known where to find Kardashian in the first place: They had been tracking her on Instagram. Using her own social media posts, they pieced together clues that pinpointed where she was staying and what, exactly, she had packed in her luggage.

I can’t lie: I derived some perverse pleasure from this plot point. Not that I didn’t empathize with Kardashian’s trauma—no one, not even the most privileged reality TV star, deserves that kind of horror—but there was something so fascinating about how the robbers had turned Kardashian’s own métier against her. The grifter got herself grifted.

Because Kardashian *is* a grifter, just as the rest of her “influencer” ilk are. Not that Instagram influencers are outright swindlers; but the bill of goods that they sell is so often based on false imagery and artifice. From the filters to the facetunes on down to the sponsored products that influencers shill, so much of social media is a giant grift bubble where nothing is at is seems on the surface, and everything is for sale.

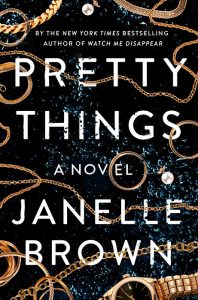

This observation became the basis of my new novel Pretty Things, about a young con artist named Nina Ross who uses social media to locate and target her marks. Much like the Kardashian jewel thieves, she pinpoints her victim’s locations and possessions by following their own posts. Nina sets her sights on an Instagram influencer named Vanessa Liebling—an heiress whose social media specialty is documenting her jetsetting fashion lifestyle—and moves into her Lake Tahoe guest house with dark intentions. Of course, as this is a suspense novel, everything goes sidewise and nothing is quite as it seems.

My initial research for the novel mostly involved con artists—their psychology, their M.O., how they work their scams in the modern age. But once that research was done, I realized that I was also going to have to do a deep dive into the culture of Instagram—deeper than I ever had before. I braced myself, and dove.

It’s not that I wasn’t already on Instagram: I’d uploaded my first photo in 2013, and dabbled intermittently ever since. But I wasn’t very good at it. The truth is that I am a failed social media early adopter. I’ve been active online since the early ‘90’s, and the Internet is littered with the profiles I’ve left behind: SixDegrees, Friendster, MySpace, LiveJournal, LinkedIn. I created my Facebook profile in 2007; and signed up for Twitter early enough to nab the handle @janelleb. But I was lackluster about them all.

So much of social media is a giant grift bubble where nothing is at is seems on the surface, and everything is for sale.My relationship to these platforms has always been one part fascination, one part longing, and one part abject addiction. Social media taps something deeply primal within us all: Our insatiable need to be seen and liked, as well as the part of us that aspires to a better live than the one we already lead. A recent study showed that some 60% of people who use social media say that it’s done major damage to their self-esteem; and yeah, that definitely includes me. Every time I logged onto Twitter I would feel like a wallflower at the school dance, standing in the corner watching the cool kids do the cha-cha slide, wondering why don’t they invite me to dance with them? I’d check whether anyone had “liked” a photo that I’d uploaded to Instagram, and when no one had, I’d wonder, what’s the point even as I kept compulsively clicking.

In the name of research, though, I committed to being “on” social media—focusing primarily on Instagram—and spent two years wading through the social media shallows. I followed the Middle Eastern oil baron wives and the South American makeup artists, the lifestyle influencers shilling “miracle” health care products of dubious provenence, the rich kids who would hashtag their gratis champagne. I followed Instagram creations like fashion blogger Danielle Bernstein of We Wore What, with her full time staff and branded line of bikinis, who left no workout or wardrobe change undocumented; and Savannah LaBrant, a Jesus-loving “mommy” influencer who dressed her blonde toddlers in identical cheetah-print pajamas in order to sell razor subscription services.

Everyone had something to sell, though mostly they were selling themselves. Nuance and personality had been traded for “brand,” authenticity was something manufactured as a marketing point. How many of these people actually resembled the creations they had so carefully nurtured for the cameras? Was social media creating a generation of monsters, aspiring to nothing more than Internet fame, and full of self-loathing for their failure to live up to unrealistic ideals?

By the time I finished the first draft of my novel, I was starting to believe that all social media was a massive huckster fraud.

And yet something curious was simultaneously happening in my feed. Even as I was following lifestyle influencers on Instagram in the name of research, I also began following book people—“Bookstagrammers,” as they dubbed themselves—for my own personal interest. These were avid readers whose personal feeds were full of nothing more than… books. Photos of books staged against pretty backgrounds; stacks of books on bedside tables with the hashtag #TBR; beautifully arranged bookshelves groaning with books; action shots of people actually reading books.

For me, these posts were an oasis of true authenticity in the desert of my social media. Bookstagram posts would pop up in my Instagram stream—sandwiched between photos of fashionistas in free #gucci posing at Coachella and lifestyle gurus hawking air fryers—and the juxtaposition was headspinning. In comparison to the influencers, these little snapshots of bookish love felt so intimate, so personal, so sincere. No one was humblebragging about their perfect lives—they were humblebragging about the ARCs they were excited to read. If there was a photo of someone’s vacation, it was purely in the context of the books they’d brought to read by the pool.

I started connecting with some members of the Bookstagram community around the time that my third novel, Watch Me Disappear, came out in 2017, when some of them started following me. I followed a few back, and those led me to even more. Eventually I realized that I’d tapped into a true community: Some bookstagrammers had 50,000 followers or more, and yet there was a cozy quality to this world, with everyone familiar with each other’s literary tastes and sharing bookish in-jokes in their Instastories. Yes, there were some who seemed to be in it to get free books from publishers; but the vast majority were there for the sheer love of reading.

As an author, this felt like a kind of nirvana: Like I’d stepped into the living rooms of thousands of avid readers across America and had been invited to peruse their bookshelves with them. How often do authors get to do this? Even on book tours, you meet only the self-selecting group in limited locales who come out to bookstore events; you get only the smallest snapshot of who your readers really are. But here, on Instagram, I could witness a mom in southern Louisiana, a studio exec in Los Angeles and a pie baker from Colorado all connecting and bonding over their shared love of novels. Amazingly, my novel.

Now that Pretty Things has come out in the world, I’ve finished my research and unfollowed the influencers; and yet I’m on Instagram more than ever before. In this era of coronavirus disconnection—with bookstores closed and readings going virtual, everyone isolated in their homes—Bookstagram feels more vital to me than ever. It’s where I go to connect with the friends I’ve made in the community, to get book recommendations from trusted ‘grammers, and to share what’s on my own shelves. The support that is mirrored back at me, as an author, has occasionally made me cry.

Bookstagram has embraced me, and I’ve embraced it right back.

So maybe it’s not exactly the case that social media is a massive huckster fraud; but that it merely amplifies what is already there in human nature. The worst, yes, certainly, but also the best: It’s a crime novel and a heartwarming story, all rolled up in one.