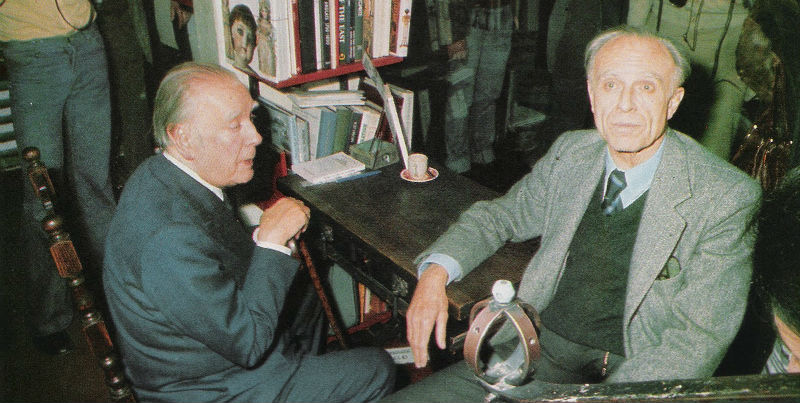

In 1945, two renowned Argentinian writers, Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, launched The Seventh Circle (El Septimo Circulo), a line of detective novels translated from English. The publisher was Emece, in Buenos Aires, and the series’ name derived from Dante’s Inferno; the Seventh Circle of Hell in that poem is the one that houses the violent. Close friends despite a substantial age difference—Borges was fifteen years older—the two men shared a love for detective fiction. In talking about his mystery story Ibn Hakkan Al-Bokhari, Dead in His Labyrinth, Borges wrote that he came to this fiction through “Edgar Allan Poe, Wilkie Collins, Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Wrecker, G.K. Chesterton, Eden Phillpotts, and of course, Ellery Queen.” He found that in “a world of shapeless psychological writing,” this form had “the classic virtues of a beginning, a middle, and an end—of something planned and executed.” He and Bioy Casares respected what can be achieved in a detective story, and they wanted to promote the genre. Until then, the reading public in Argentina had looked upon mysteries as amusing confections at best. They were items to be bought at a newspaper stand, read quickly, and thrown out. In Argentine culture, neither the critics nor ordinary readers had considered the idea that a detective story could be literary. But the two editors, through the books they chose for their imprint, set out to dispel that notion.

As the authors cited by Borges suggest, the crime fiction he and Bioy Casares preferred were complex tales of detection. After kicking off the series with Nicholas Blake’s The Beast Must Die, they followed up with novels by John Dickson Carr, Michael Innes, and Anthony Gilbert. Borges and Bioy Casares had a predilection for British mystery writers, and from 1945 to 1955, when they ran The Seventh Circle, the majority of books they selected were from Britain. They did make exceptions—titles by James M. Cain, Vera Caspary, and Margaret Millar—but what the pair most wanted to display to Argentinian readers were confounding puzzles and whodunnits with clues, narratives where disorder hides behind the scrim of respectability and brutality squares off against the cerebral.

They had, under the name H. Bustos Domecq, collaborated on a detective story collection before creating The Seventh Circle. This book was Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi (Seis problemas para don Isidro Parodi), published in 1942. Inspired by sedentary sleuths like Baroness Orczy’s The Old Man in the Corner and Ernest Bramah’s Max Carrados, Parodi is an armchair detective taken to an absurd degree. He’s a man who has been imprisoned for a murder (wrongly), and who solves crimes from a jail cell. Famous in Buenos Aires for his mental abilities, he receives visitors in his cell, and while he smokes cigarettes, brusque and aloof in his manner, they present “the mystery that troubles them.” On their second visit, they hear the solution, “which astounds young and old alike.” Through a tongue in cheek forward written by a fictional critic about Domecq, Borges and Bioy Casares lay out their purpose and method. The critic states that “an Argentine hero has made his appearance in a purely Argentine setting. What an uncommon pleasure it is…to savor a detective story which does not obey the rigid rules of a foreign Anglo-Saxon market.”

In actuality, the six stories are exaggerated versions of Anglo-Saxon detective fiction, working as both parodies and genuine mysteries. The “Nights of Goliadkin” features a phony priest calling himself Father Brown and takes place on a sleeper train filled with ridiculous, secret-laden passengers. “The God of the Bulls” has an impossible crime taking place on an isolated estate, but this being Argentina, the estate is on the pampas and a prime suspect is a man obsessed with gauchos. “Tai An’s Long Search” is narrated by a Chinese man, whose extreme humbleness and amiability seem to mock a stereotype in part reinforced by the Charlie Chan novels. Borges and Bioy Casares wrote stories that entertain in Don Parodi, but at the same time, to a certain extent, they deconstruct a genre they love.

***

The stories also illuminate Argentina in the early 1940’s. The tail end of what became known as the “Infamous Decade,” this was a period, before the rise of Juan Perón, marked by fraudulent elections and corruption. Though not known as political writers, Borges and Bioy Casares do present a great deal of social commentary in the book, integrated into the convoluted plots. “A satire on the Argentine,” is how Borges, in his “Autobiographical Essay,” describes it, and what a barbed picture the book gives. Starting with the verbose fictional critic, Gervasio Montenegro, who writes the collection’s forward, pomposity and falsehood are everywhere. Class divisions cause problems, families implode because of rivalries and cruelty, there’s a large divide between rural people and urban, and everybody seems to be commenting on the foreign roots of other people, though Argentina is a nation of immigrants. Not a single person who comes to Don Parodi with a story uses language in a direct manner; voice after voice he listens to is florid and deceptive. His logic cuts through all the pretension, and when he speaks, he is concise and clear. In a world of the self-serving, of dupes and schemers, Parodi stands for intellectual honesty. That he is in prison, and for a crime he didn’t commit, emphasizes the topsy-turvy quality of the world he inhabits.

Four years later, Bioy Casares collaborated on a second mystery, this one a novel. Written with his wife, Silvina Ocampo, Where There’s Love, There’s Hate (Los que aman, Odian) came out in 1946 from Seventh Circle. It would be one of the few Spanish language works the imprint published.

Ocampo, like her husband and Borges, was a major writer, a prolific author of fantastical stories, poetry and children’s books. Borges called her “one of our best.” Where There’s Love, There’s Hate is a light piece for her and Bioy Casares, but that’s not to say it’s not erudite. Though more restrained in its language than Don Parodi, it too functions as a legitimate detective story and an Argentinian send-up of traditional British detective fiction.

In a world of the self-serving, of dupes and schemers, Parodi stands for intellectual honesty. That he is in prison, and for a crime he didn’t commit, emphasizes the topsy-turvy quality of the world he inhabits.A group of guests at a seaside hotel, in Bosque del Mar, Argentina, find themselves dealing with a couple of murders and the annoyance provided by fellow guest Humberto Huberman. He is a doctor and writer who, despite the arrival of the police to investigate the killings, takes it upon himself to conduct an inquiry. Puffed up with confidence, he suspects every guest in turn, and he never seems to lose faith in himself when his theories about the crimes are proven wrong. Tensions build, guests and hotel staff quarrel. The story climaxes during a night time windstorm and a search through blinding sand that leads to a nearby beached ship called the Joseph K.

In Don Parodi, Borges and Bioy Casares created a number of voices, but a single narrator tells Where There’s Love There’s Hate, and that’s Huberman. He has a pretentious but literate voice, and one gets the sense that Bioy Casares and Ocampo are having fun with him, giving him lines such as: “When will we at last renounce the detective novel, the fantasy novel and the entire prolific, varied and ambitious literary genre that is fed by unreality?”

This seems like an inside joke between husband and wife since each wrote numerous books where unreality, so-called, the dreamlike and the bizarre, dominate. Most of their novel carries this mock-serious tone, and unlike in Don Parodi, social critique is all but absent. The focus throughout remains on detection and literary hijnks. Huberman is working on a screenplay adaptation of The Satyricon, one victim is a translator of popular fiction, and a key toward getting to the mystery’s solution hinges on a misunderstood handwritten passage the translator had put on paper just before being killed. However, Where There’s Love, There’s Hate did come out during the beginning of the Juan Perón era, and neither Bioy Casares nor Ocampo (as with Borges) were fans of the strongman. The book’s remote setting means the outside world doesn’t have to intrude, but there is one passage that seems to refer to the Argentinian political climate. Huberman, who perhaps represents a segment of the intelligentsia, contemplates his general attitude and conduct as they relate to the authorities:

“Then I asked myself a more important question: Why had I, having adopted as a fundamental rule of conduct never to expose myself to danger, never having signed any protest against any government, having favored the appearance of order over order itself, if in order to impose it violence would be required, having allowed people to step all over my ideals, in order not to defend them; why had I, having aspired only to be a private citizen and, in the lap of luxury of my private life, find the “hidden path” and refuge against dangers both external and within; why had I – I again exclaimed – involved myself in this preposterous story and followed Atwell’s [a police investigator] senseless orders?”

The phrase “senseless orders,” in the wake of World War II, has a particular resonance. And Argentina had a specific history in relation to that war. Well before 1939, with its large population of German immigrants, Argentina had maintained close ties with Germany. The Argentine military and the Prussian military had a bond dating back decades, and the Argentine commanders urged their government to stay neutral through the conflict. Even after Pearl Harbor and despite US pressure to join the Allies, the Argentinian government did not budge from this position. It was not until March of 1945 that Argentina declared war on Germany, and as for what happened right after the war, Juan Perón would later say, in Yo, Juan Domingo Perón (recordings done before his death and then published as a book), “In Nuremberg at that time something was taking place that I personally considered a disgrace and an unfortunate lesson for the future of humanity. I became certain that the Argentine people also considered the Nuremberg process a disgrace, unworthy of the victors, who behaved as if they hadn’t been victorious. Now we realize that they [the Allies] deserved to lose the war.”

It seems almost logical that Argentina, with the war over, would become a primary refuge for Nazis, and under Juan Perón’s direction, it did. His government helped as many as 300 war criminals escape. Through a network run from the presidential palace in Buenos Aires, German Nazis as well as collaborators from elsewhere in Europe came to Argentina and settled. Despite the clandestine nature of the network, the presence of Nazi escapees in the country was not unknown to the public, and against this background a novel emerged that became the forty-eighth title released by Seventh Circle. It was Manuel Peyrou’s Thunder of the Roses (El estruendo de las Rosas), published in 1948.

This novel takes place in an imaginary republic turning ever more authoritarian. It could be Argentina of 1948, but characters have Germanic names, and as Borges says in his introduction, the country “also stands for the Third Reich.”

The mystery that sets the book going is perplexing and ingenious. The nation’s leader is shot on a terrace while delivering a speech being broadcast to the entire country, and after the assassin is arrested, a police investigator informs him that he killed the dictator’s double. The real “chief and Fuhrer” had been murdered the night before in his apartment, “shot through the heart.” The double, in the investigator’s words, “had taken his place in order to prevent the country from becoming alarmed while we determined a plan of action.”

The investigator reasons that the assassin made an error. But since the assassin intended to kill the leader, not a “puppet,” he will be judged for that act. Still, the investigator offers him a way out and says that his case will be reexamined if he helps uncover the murderer of the leader. The assassin has ties to the opposition, and someone from that circle must have committed the first crime. The security forces will grant the assassin conditional freedom if he agrees to help them.

He does agree, and for the duration of the novel, in Borges’ words, “things are not what they seem, or, as Chesterton would say with superior rhetoric, mean nothing here but mean something somewhere else. Not even the crime is what we believe it to be; the entire book is a shifting game with masks and mirrors. The plot, in accordance with the requirements of the canons, is complex but not complicated; the unexpected final revelation does not require us to refer back to pages we have read.”

Like Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi and Where There’s Love, There’s Hate, Thunder of the Roses satirizes detective fiction while having a self-referential aspect. Embedded in the story is a remarkable essay attributed to the man who shot the dictator’s double. As the investigator discovers, the assassin loves to read detective novels, and the essay found among his papers is called “Hamlet and the Detective Story.” This piece compares Shakespeare’s play with Nicholas Blake’s 1938 novel, The Beast Must Die. If you recall, The Beast Must Die was the first title Borges and Bioy Casares chose for The Seventh Circle imprint. The assassin’s essay looks at Hamlet as “the dramatic account of an attempt to commit the perfect crime; and among other things, it is suggested that if in 1940 the perfect crime is the one that goes unsolved, in 1600 it was the one which could be morally justified.” The Beast Must Die concerns itself with a man trying to commit an undetectable murder, Hamlet with the moral quandaries the Danish prince broods over. It’s quite a funhouse Peyrou constructs: his novel, set in a fictional country, has an essay about two works from the actual world. What’s more, the assassin’s essay helps elucidate the novel he is in. The attempt to commit the perfect crime and the moral justification behind the killing of a dictator are central components in Thunder of the Roses.

So is a subtle topicality, a sly wit. It’s difficult not to see this passage as an analysis of the sort of populism that was showing itself in Argentina under Juan Domingo Perón:

“Bostrom [successor to the murdered head of state] and his friends used a popular and sometimes coarse form of speech which was praised by their followers because of its supposed simplicity. It was said that its use was proof of an open frankness and that it constituted an authentic point of contact with the common people. The truth of the matter was that they spoke in that fashion because they knew of no other. It was, after all, a familiar practice to turn all deficiencies into virtues. If an individual was basically ignorant, he was praised for his common sense and his ability to skirt abstract problems; if he was hasty and coarse he was admired for his frankness and his dislike of dilatory techniques; if he was indecisive and slow, he was applauded for his caution.”

Writing with lightness, using a genre associated then with “mere” entertainment, setting his story in a made-up country, Peyrou manages to engage with the political atmosphere of his time. The novel is a bravura performance.

***

In September 1955, a military coup ousted Perón from power, and that year, after putting out 121 books, Jorge Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares turned the directorship of The Seventh Circle over to a new editor. They helped release several more books, though, and among this batch of choices was another Argentinian one, Maria Angelica Bosco’s Death Going Down (La muerta baja en ascensor). It’s a straight procedural mystery, more realistic than Manuel Peyrou’s book, but it too touches on Argentina’s connection to the Nazi era.

A woman named Frida Eidinger is found one night lying dead in an apartment building elevator. The police quickly establish that she was murdered, and they set about questioning people who moved within her orbit. Eidinger, obviously, is a German name, and the clues in Bosco’s mystery lead back to events that happened in Germany during the war years. Immigrants in Argentina who have questionable pasts are at the heart of this book, and while some of these characters have no qualms over earlier actions, others are haunted. No matter how hard they try, they cannot repress disturbing memories.

From the dark, empty space came faces contorted by torture. Faces that had one day smiled at her in her home far away in Germany, but had then been disfigured by death before disappearing forever from the world of the living. Rita trembled under the blankets: “They’ll always come back, Boris…I’m scared…I can’t make them go away.”

Character names reflect the ethnic mix Borges and Bioy Casares explored in Six Problems for Don Isidro Parodi: Death Going Down gives us Santiago Ericourt, Ferrucio Blasi, Adolfo Luchter, Superintendent Lahore, Boris and Rita Czerbo, Pancho Soler, Aurora Torres. Within the structured confines of a whodunnit, Maria Bosco couches a social study of mid-nineteen fifties Buenos Aires, and her book’s immediate popularity in Argentina testifies to the relevance of the issues she was broaching while telling an excellent story.

The Seventh Circle line continued until 1983, publishing 366 novels in all. Over time, after Borges and Bioy Casares left, the imprint published more hardboiled crime writers, such as Raymond Chandler and Ross MacDonald and Joe Gores. The new editorial leadership liked this mode of fiction more than Borges and Bioy Casares had, and with its ability to portray violence and corruption and political brutality, hardboiled crime better matched the day to day reality of Argentina as it lived through decades like the 1970’s. That was the decade of the “Dirty War,” right-wing death squads, and the “disappeared.” Make no mistake, though. As the founders of The Seventh Circle, through their choices for the collection, Borges and Bioy Casares did much to elevate the stature of the mystery genre in Argentina. They did their part to help bring mysteries to a wider audience and to break down the silly barrier that once separated crime fiction from what some call literary fiction.