May 4, 2015, Boss/Brooks

My fellow passengers on the flight from Dallas to San Angelo were an interesting mix of people: oil company men, dressed in jeans, T-shirts and dusty boots, headed back to the fracking fields of West Texas; a woman with a fidgety young son going home after a visit with relatives in Louisiana; a cluster of servicemen returning for duty at Goodfellow Air Force Base, where members of all service branches studied cryptology, the art of deciphering secrets.

And there’s me, on a deciphering mission of my own.

I sat forward of the wing, watching through the window as the plane bulldozed through white clouds. When I departed Nashville, the weather was hot for early May, but coming out of an exceptionally snowy winter, the warm spell felt good to the bones. Awaiting me in West Texas was a front of howling winds streaming down from the Rockies, the kind that swept tumbleweed across dusty rangelands, but were also capable of producing thunderstorms and possibly tornadoes. Following the rain, the temperature was expected to rise into the nineties.

I did not know what to expect on this trip, for more reasons than Mother Nature and I was apprehensive. Too unsettled to read, I stared out the window. Occasionally, there was an opening in the clouds, and I saw the ground transforming by the mile, the dark green of East Texas yielding to lighter hues until the earth turned a pale palette: hills the color of aged parchment and fields striped with crops: cotton, corn and wheat, among others.

Rivers, whose names were unknown to me, appeared like ribbons fallen from a little girl’s hair. The channels of dark water twisted and turned, sometimes almost doubling back on themselves. I followed their curves until our flight path veered away and they disappeared into the horizon, only to have another unknown river catch my eye.

The jet cruised at 23,000 feet, retracing the journey of my paternal grandfather, whom I never met, but whose absence in my life created an emptiness I sought to fill. Now retired, there was time to pursue his past. I spent thirty-eight years in the human resources department of Gannett, owner of Nashville’s largest daily, The Tennessean. At the age of twenty-one, I entered the newspaper’s 1100 Broadway office, several blocks east of Music Row, to begin work. I was the least senior person in the office, but I learned the job, I liked the people and I stayed until retirement in 2014. When I exited I was head of the department.

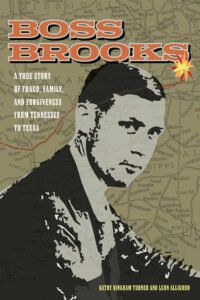

During my decades at the newspaper, I developed a nose for news. Consequently, when I examined my grandfather’s story, I was surprised by how little I knew. What began in my last two years of employment as idle curiosity became an obsession. I immersed myself in genealogical research and quizzing relatives. I wanted to uncover the complicated truth about my grandfather, a man who faked his death and got away with it.

By the time Lytle Boss Bingham was born in 1895, the oldest son of a farming couple, the Binghams had been raising crops in the bottomlands of the Tennessee River for three-quarters of a century. Boss was a farmer but exhibited a talent for mathematics. After high school he spent a year in business school and returned to work at Hardin County Bank as assistant cashier while he farmed on the side. He married his sweetheart, Mary Louise Brooks, in 1916 and over the next fifteen years they had four children. The oldest, a boy named James Thomas, died shortly after birth, most likely to delivery complications. The next two children were girls, Margaret Lois and Mary Lou. Their baby brother, the youngest, was my father, Lytle Brooks Bingham, who inherited his father’s forename. Brooks was his mother’s maiden name.

My dad was two when his father disappeared from Saltillo on January 14, 1931. Boss told my grandmother he must attend to banking business out of town. He disappeared into the night. My grandmother, my aunts and my father never saw him again.

The following morning his black Chevy coupe was found consumed by fire on a state highway several miles south of Jackson, Tennessee. Deputies found one occupant, burned beyond recognition. Several of my grandfather’s closest friends identified the charred corpse as that of their banker and Sunday school director at Sulphur Well Church. That was enough for the county coroner, who was also a funeral director, to issue a death certificate for Lytle Boss Bingham. A day later, a funeral was held in Shady Grove Cemetery and, after some months, a headstone bearing only my grandfather’s name, the year of his birth (1895) and the year of his death (1931) was erected.

When I was a child, I was told this narrative of my grandfather’s death, but the story was a lie, a web of obfuscation spun by my grandmother and others. The truth is my grandfather did not die in a fiery crash in 1931. The charred body found in his burned car was not him, but a stolen cadaver.

I now know my beloved grandmother, a steadfast woman of prayer who memorized many Bible verses, helped in no small way to perpetuate this deceit, as well as to commit insurance fraud. In court appearances resulting from lawsuits filed against life insurance companies, my grandmother raised her hand to swear the truth and testified her husband was dead, when she knew he was alive. With the help of family members and friends in Saltillo, and a considerable measure of luck, Boss Bingham successfully convinced the world he was no longer alive.

Among his family, neighbors and even many of the bank depositors who lost all they had during those fragile years of the Depression, Boss was described “as a fine man,” an individual of purpose, possessing integrity and honor. He was a man, many suggested, who would sacrifice himself for the greater good. By others, however, he was portrayed as an absconder. Some depositors who lost their savings viewed him “as a damn crook.”

I spent years reconciling these contradictory descriptions about the grandfather I didn’t know and the actions of my grandmother, whom I knew very well. Or thought I did.

My questions led to more inquiries, but my quest to define my grandfather was not always welcomed, not only from relatives but from others in Hardin County who mythologized my grandfather. He was remembered either as a cashier who cashed in, at the bank’s expense, or as a hero of the Depression for refusing to foreclose on dozens of farms and homes belonging to his family and friends. My search for truth has been as frustrating as it has been exhilarating and exhausting. For every definitive answer found, new questions emerged.

I could not find all the answers in Tennessee. That’s why I was on a plane soaring over the Lone Star State following the route Boss began in the winter of 1931. My eventual destination is the dusty town of Sherwood, Texas, a short drive west of San Angelo. This is where my grandfather fashioned a new identity, Marvin Lester Brooks. This is where he recuperated from tuberculosis, camping beside a creek for more than a year, where he bought a farm and raised cotton, where he waved at neighbors as he passed by in his pickup and where he was so highly regarded by voters that he was elected to the Irion County Commission for three consecutive terms.

Sherwood is where he met and married another woman, with whom he had four children. My Texas family. They awaited my arrival, prepared to share their father’s life: where he lived, worked and where he died a second time. On this journey, I will visit my grandfather’s grave and touch the tombstone that marks his real final resting place.

As the state of Texas slipped beneath me, I questioned if I was prepared to interrogate the children of my grandfather’s second life. I’m conflicted because the man they refer to as “Dad” is the same man who abandoned my father and his two sisters, the grandfather who never bounced me on his knee. And, most significantly, he was the husband my dear grandmother lost forever.

Yet, I looked forward to getting to know these new relatives. I wanted to hear their stories of my lost grandfather: what made him laugh, the nature of his disposition, his thoughts on living a double life. I was curious if I recognized traits of my Tennessee relatives in the Texas siblings. In the sons, would I see my father? I anticipated sharing their memories so I might feel connected to this man who thoroughly disrupted my family.

So many questions to ask; so much to understand.

If I had been a curious child, I might have asked my grandmother about my grandfather’s simple headstone at Shady Grove Cemetery. Unlike other grave markers, where loved ones were remembered with engraved words of endearment, the upright slab marking my grandfather’s grave stood practically mute. In recent years I have come to understand that the simple marker represented a loose thread in the fabric of my family’s history.

And now was the time to pull that thread.

___________________________________