I used to fight out of the Harrowgate Boxing Club in Philadelphia. Amateur. When, after two years there, I asked my trainer if I should turn pro, he likely recalled my previous few bouts, bloody battles in which I absorbed far too much punishment and inflicted much too little damage. He hemmed and hawed then said, “Well, you do a nice job of hitting guys in the fist with your face.”

So I went away to school, fought for a couple more years at the collegiate level, then quit the fight game for good.

Funny thing though—it has been decades since I’ve been in a ring, yet no day goes by that I don’t think of boxing. I recall opponents. Reconsider strategies. Wonder what if, what if, what if.

That’s because, just as a deep cut leaves behind a lifelong scar on your flesh, fighting leaves behind an oversize imprint on your psyche. Its memories are slow to fade. Its lessons are painfully learned, and they last.

The biggest lesson is this: Many times you must move toward the punch. To do so, you must stand closer to your adversary. That sounds reckless. Counterintuitive. Foolhardy. But it’s vital to your survival in the ring.

If the other fighter throws a hook and you step toward him, the punch may just sail around the back of your head and miss. And if he launches a straight fist, the shorter the distance it moves, the less damage you suffer if it lands. You try to smother the punch by getting right up next to the puncher.

You learn: Get nearer to the thing that can hurt you.

*

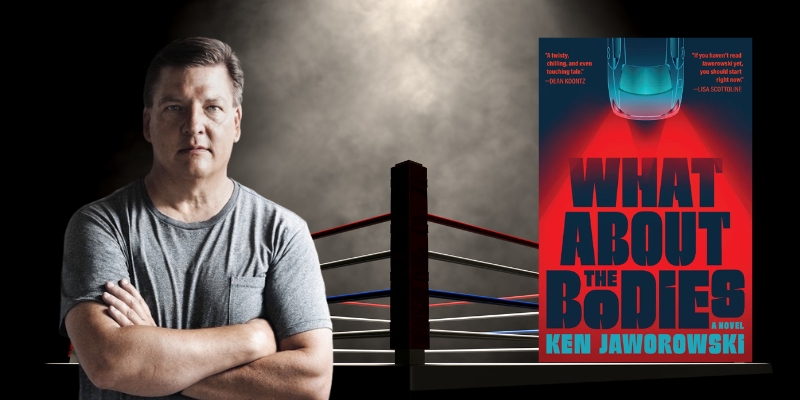

After writing my new thriller, What About the Bodies, I was asked by my publisher’s marketing team to deliver to them an elevator pitch—a pithy summary of what the novel is about.

Recounting the plot during that conference call was easy enough: A struggling single mother, a down-and-out musician and an autistic young man get tangled up in crimes in a small town in Rust Belt Pennsylvania. The three refuse to run away, choosing instead to fight to save themselves or those they love.

There are funny jokes, too.

That’s a really nice elevator pitch, I was told. Then they asked: What is the book’s overriding idea?

I paused then blathered and babbled until someone had mercy and told me to come back after I had thought it through.

When the call ended, I took a long walk. Reflected on the story’s two women and a man, and on what they were doing.

I stopped walking.

Then I started to nod, because I suddenly, and fully, understood these characters and their overriding idea: All three were moving toward the punch. They saw danger and walked into it. They felt fear, yes, but they were determined to do what might seem, to some, irrational.

The world could harm them, they knew. So maybe they should get nearer to it.

And perhaps later, joy might follow.

*

There’s as much poetry in the boxing ring as there is in an Ivy-League library, if you know how to look. It’s a brutal sport, and one that can be difficult to defend when seeing the injuries and the heartbreak it inflicts on some of its practitioners.

It’s been said that boxing takes what is most ugly in a person and puts it center stage for all to see. That is true. Yet it also takes what’s most rare, and what’s best in us—courage, tenacity, soul—and displays that beauty as well.

Fiction does something similar. It can make us outright happy, sure. But sometimes, it’s there to make us less sad. It brings us closer to the things we fear, and for good reason. Just read the ancient Greeks. They knew the secrets of storytelling, and of fighting.

They liked funny jokes, too.

Yet they understood catharsis, the renewal that could arise after experiencing our own or another’s deep emotions. The original word itself, katharsis, means purification, cleansing, purging.

Indeed, tough scenes and piercing words can serve “as the dark backing that a mirror needs if we are to see anything,” as Saul Bellow sort of said.

There’s as much poetry in the boxing ring as there is in an Ivy-League library, if you know how to look.Maybe those scenes and words bring us nearer to what can hurt us.

That can lessen the pain of life.

And perhaps later, joy might follow.

***