Once upon a time, at the end of the last century, Nick Hornby’s million-copy bestseller About a Boy was released, to be followed four years later by a heartwarming movie adaptation starring Hugh Grant. If you’re like me, you might already have it slated for rewatching this coming holiday season. But did you know that Hornby’s novel was itself a reference to a Nirvana song called “About a Girl?”

Popular titles seemed to bounce between the genders until we hit the “girl” thriller era and everything changed. Forgive me for pointing out the staggeringly obvious in order to establish a timeline, but we’ve lived through two full decades of “girl” titles now, from The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2005) to Gone Girl (2012), The Girl on the Train (2015), and Girl A (2021).

Less interesting than the proof that publishing thrives on imitation were the meanings behind those titles. “Girl” thrillers often featured female protagonists with agency and complexity. Many utilized unreliable narration. While the titling trend itself became a cliché, the books weren’t, with an emphasis on female empowerment, revenge, or reinvention.

I doubt many of us thought the “girl” trend would last quite this long. But to quote a 1976 song by Irish band Thin Lizzy, “The Boys Are Back in Town.”

The reasons behind this change interest me the most, but first let’s look at the titles and topics themselves.

In television:

- The Boys (Prime Video), a satirical superhero series wrapping up its fifth season in 2026, starring a shockingly violent narcissist named Homelander and various other thugs

- Adolescence (Netflix) with a gender-neutral title but an undeniably boycentric plot, featuring a thirteen-year-old suspected of a deadly knife crime

- Bad Boy (Netflix), an Israeli TV show about a boy in juvenile detention, demonstrating that violent boys who can’t be controlled by their despairing mothers aren’t limited to English-language programming

In nonfiction, where the subtitles tell even more of the story:

- Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It by Richard V. Reeves (2022)

- BoyMom: Reimagining Boyhood in the Age of Impossible Masculinity by Ruth Whippman (2024)

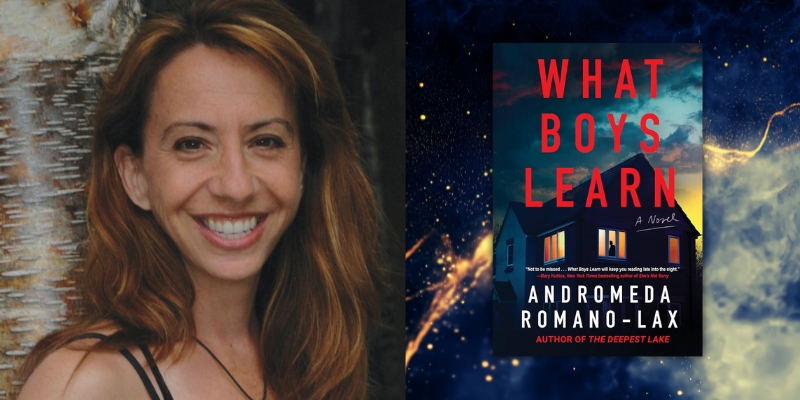

My own next novel, What Boys Learn (January 6, Soho Crime), is about a single mother who suspects her secretive, antisocial son may have been involved in the deaths of two female classmates. I picked the title based on my own concerns about what boys really are learning—most of it worrisome—from the world around them. When I started the book, I didn’t realize how many other writers and TV creators were asking the same question.

The pessimistic slant, I’d argue, is both earned and verging on a trend. To see how much things have changed in the last decade, consider what our assumptions used to be when we encountered “boy” in a title.

As recently as 2008, a thriller called The Boy by Tami Hoag invited us into the story of an innocent youth who was witness to a crime. Likewise, The Boy in the Field by Margot Livesey (2020) was a whodunit that centered upon the discovery of a boy victim. In Harlan Coben’s The Boy from the Woods (2020), the eponymous feral boy had grown up to become a justice-inclined man who helps locate missing people.

Boys used to be blameless—or so we preferred to hope, in our fiction. But most references to “boys” or “men” land differently now.

In media portrayals, a boy is no longer seen as a victim—even though boys frequently are. (Young men are more often victims of homicide and physical assault than women, for example, while women are more often victims of sexual assault and sextortion than men.)

Vulnerability to violence aside, boys are still feared as incels, potential school shooters, or at the very least, as young people struggling academically and socially.

Parents, especially mothers, question how to raise boys in an era of toxic male influencers. Across the political divide, researchers document low achievement by boys and wonder about systemic failures in terms of education and mental health.

To be fair, some commentators feel the boy crisis is overblown. But more of us, I’d argue, worry about boys and what they are learning from the stories of powerful men who succeed through violence—or simply by being vile.

My teenage character, Benjamin, is all too aware of the pattern set by male celebrities, moguls, and politicians. Benjamin’s mother Abby, who has just lost her job as a school counselor in the book’s opening pages, is the altruistic loser who hasn’t figured out society’s new rules, he tells her.

The title of Sameer Pandya’s Our Beautiful Boys—a title that intends to communicate melancholy and a longing for the past, according to the author—doesn’t refute this trend, but only underlines it. The 2025 novel is about three football players who assault another schoolmate and the families who must reckon with the fallout.

As Pandya told me by email,

I think we are certainly in a moment, not just in books and movies, but also in a broader social conversation, where young men are presented as problems. And there is plenty of evidence for this concern.

And yet, as a novelist, my job is to take the four boys at the heart of my book and give them a level of interiority so that we can begin to understand how they think of themselves, how they relate to one another, what sense of possibility they feel. What is the source of despair? How does class and race shape the ways in which these boys perceive themselves?

Another “boy” thriller that asks us to make more than one interpretation of its title is Deborah Goodrich Royce’s forthcoming psychological thriller, Best Boy (Feb 2026). Royce told me she enjoys playing with double and even triple entendres. The boy in the title refers to the moviemaking job of a “best boy,” or assistant to the crew electrician. It also refers to the main character’s beloved son, Theo—proving that “boy” can still equate with purity and goodness, at times.

But the third three-letter reference is indeed a callback to something terrible that happened in the female protagonist’s past. Violence, unreliable memory, and questionable blame connect the novel’s multiple timelines.

As the author of a forthcoming boy-titled book, I ask myself if this focus on boys and crimes they may or may not have committed is adding to an important cultural conversation or feeding into a moral panic. Do we worry too much about boys? Conversely, are we worrying too little and condoning too much?

As the author of a forthcoming boy-titled book, I ask myself if this focus on boys and crimes they may or may not have committed is adding to an important cultural conversation or feeding into a moral panic.My main character, Abby Rosso, has made excuses for her son’s conduct for years. Despite her degree in psychology, she has trouble getting at the roots of his behavioral issues.

I hope readers will relate to Abby’s feelings, that teenage sons can seem unknowable. Our cultural moment—including the pernicious effects of social media and the confusing messages boys receive about how men should act—has made the job of parenting boys harder than ever.

As crime novelists, we concoct plots inspired by own anxieties as well as the violence, fear, and uncertainty we observe around us. Social issues are complex.

Titles, on the other hand, usually can’t be. Often, what we are trying to call attention to boils down to a single, fraught word. My prediction for the coming decade is that one of those words will be “Boy.” Watch for it.

***