After some crown jewels were stolen from the Louvre, there’s been a lot of interest in heists, especially involving museums. Our book Stealing Time, which came out before the Louvre, involves a heist inspired by the real-life 1964 burglary of the American Museum of Natural History, masterminded by Jack “Murph the Surf” Murphy, who stole the Star of India and other gems. (The Star of India and others were recovered, but many others remain missing.)

To make sure we nailed the heist genre, we watched dozens of heist movies and read heist novels, focusing on those targeting diamonds and jewelry. We identified ten categories within the genre, although it’s important to note that some fictional heists may comprise multiple categories.

Classic: These begin when the brains of the operation assemble a crew, each of whose members has a specific, usually nefarious skill. They then develop an intricate plan for a high-stakes robbery: diamonds, bearer bonds, or some other fabulous item serving as the MacGuffin, the term Hitchcock used to refer to the plot device that sets everything in motion. In more recent movies, the gang is likely to procure uniforms, blueprints, intel such as the timing of the guards’ bathroom breaks, and all kinds of expensive equipment to pull off the job. The gang then prepares for the big day and tries to avoid problems with the antagonist, who could be the police, the MacGuffin’s owner, or a rival gang. They execute the heist, dealing with twists or double-crosses, and may or may not make the getaway. Examples: The Ocean

Comedic: In comedic heists, also known as capers, bumbling crew members cause things to go wrong in a funny way, with the MacGuffin switching hands from the gang to its rival, sometimes repeatedly. Comedic doesn’t mean an absence of violence: Guy Ritchie’s and Quentin Tarantino’s films can be both funny and brutal. In comedic heists, we’re rooting for the main characters, who typically walk away with the MacGuffin. Examples: A Fish Called Wanda (1988), The Hot Rock (1972).

Tragic: Tragic heists are characterized by failure, incompetence, betrayal, greed, or all of the above, leading to tragic consequences for the crew. Early tragic heist movies, like The Asphalt Jungle (1950), came out of the noir tradition; frequently, down-on-their-luck protagonists get cheated by fate and irony. The challenge for these movies is to make us care what happens to reprehensible characters.

Nonlinear/Deconstructed: In movies like Reservoir Dogs (1992) and The Usual Suspects (1995), the action opens after the heist has imploded, then circles back to introduce everyone. The rest of the movie unfolds nonlinearly, merging the past (establishing the target, the plan, the characters, and their motivations) with the present to show what went wrong. These stories are often meta-criticism, playing with the classic heist tropes and structure or exploring the emotional or physical toll. They can be challenging to write because, despite our knowing that the heist was unsuccessful, the movie still has to have an emotional payoff at the end, or we will feel robbed. So to speak.

Revenge: The MacGuffin is not the main motivation in revenge heists. In movies like Thief (1981), the main character needs to hurt the villain, and killing them isn’t enough. This genre can overlap with others: The Italian Job (2003) uses a classic heist structure as the crew seeks revenge on a former partner who double-crossed them. But revenge is paramount.

Solo: Not all movie heists need an extensive gang. Some are conducted by one person. These movies, like Thief or The Thomas Crown Affair (1999), tend to be character studies, focusing on the journey of the protagonist against the surrounding forces of evil, with revenge a key element.

Paranoid: You can trust your fellow gang members in movies like Ocean’s Eleven (1960 & 2001). But in others—like Thief, King of Thieves (2018), or those below in the “Twist” category—you can’t trust anyone. Not individual crew members; not the brains, the moneymen, the fence, or even the (dirty) dirty cops. Like their cousin, the revenge heist, paranoid heists can overlap with other categories—or that’s what they’d like you to think.

Twist: Misdirection is a key aspect of many heist movies, where the character knows something the viewer doesn’t. Whereas classic heist movies are fairly straightforward, the endings of twist movies play tricks on the audience as much as on the antagonist. Examples: Reservoir Dogs and The Usual Suspects.

One Last Score: The crew can either be looking to pull one last score before retiring (Thief) or coming back from retirement (King of Thieves). Will they get along again? Will they be able to pull off a heist? These movies can operate across several other categories, including classic, comedic (security technology has changed significantly since they last pulled a job), tragic, and revenge. For what it’s worth, with our current group of older, active actors, we expect this subgenre to remain popular until they retire. (Looking at you, Morgan Freeman, Annette Bening, Michelle Yeoh, Pierce Brosnan, Helen Mirren, etc.!)

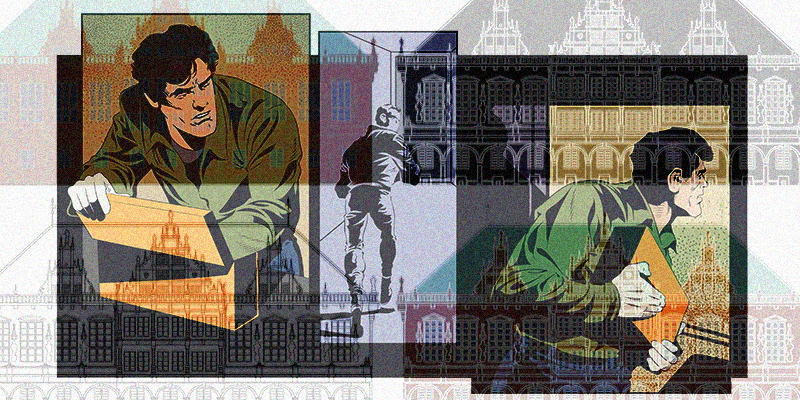

Reverse: Instead of stealing something, the character must return, replace, or protect the MacGuffin. What makes it more challenging is that the characters must do so without getting caught. Examples: National Treasure (2004), The Thomas Crown Affair, and our book, Stealing Time.

One thing to keep in mind is that the way heists play out has changed over time. In the 1940s and 1950s, gangs were bad guys, and they typically got caught or killed. That mostly changed in the 1970s, when audiences were encouraged, by sympathetic antiheroes and loveable rogues like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), for example, to root for the criminals to succeed. No doubt some are rooting for the Louvre thieves to succeed, since it was such an audacious crime—in daylight, while the museum was open to visitors. Based on what we’ve read, theirs was a Classic heist with a possible Twist since the gang has been arrested and the jewels remain missing—so someone has them.

If you’re a writer, understanding the different plot types can help you choose the structure, tone, and stakes that best serve your story. If you’re a reader, recognizing different types may deepen your appreciation of the art behind the heist.

***