I have practiced international law in Washington, D.C., London, Berlin and elsewhere for more than three decades, beginning many years before I started writing my first spy thriller. During that time, I have had the privilege of handling some of the most interesting international legal disputes of our generation.

My first international case was against the Republic of France, where I represented Greenpeace in obtaining damages from France for the illegal mining of the Rainbow Warrior — Greenpeace’s very peaceful protest vessel — in Auckland Harbor, New Zealand. Although the involvement of French intelligence agents in the bombing started out as a secret, a combination of good detective work by New Zealand and Greenpeace, and an internal investigation by the French government, revealed the secret. And made my job in seeking hefty compensation in the following international arbitration a lot easier.

I also had the privilege of representing the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement/Army in a dispute with Sudan over their national boundaries. That case, too, required unearthing many secrets, hidden in dusty archives in London, Khartoum and elsewhere. It also required other historical research, into both British colonial rule and traditional tribal lifestyles and cultural sites. I was privileged to represent South Sudan in uncovering all of this and then in defending its ancestral rights in the Abyei Arbitration.

Those cases, and international law more generally, are important and can be fascinating. I have loved almost every moment of the cases that I have handled. But I think we all know that most kinds of law, including international law, aren’t really that high on either entertainment value or action.

It’s true that legal thrillers, like John Grisham and Lisa Scottoline, are a popular genre — usually fast-paced and entertaining. The fact that some types of law involve high-stakes disputes and complicated characters helps explain the phenomenon. But it’s still incredibly hard to turn most types of law, including most courtroom trials, into spy thrillers.

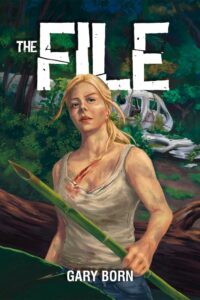

So, when I sat down to write my debut thriller, The File, I didn’t try to write something about the law or about a courtroom. In The File, you won’t find a single lawyer, courtroom, judge or jury. Nowhere. Not even in the wings.

Nevertheless, the novel involves law in a variety of other ways. Reflecting on the book, I think those aspects of the thriller are extremely important to the book, and were also important to the process of writing the novel.

The File is partly about money — lots of it — that was secretly hidden decades ago by the Nazis, at the end of World War II, in numbered Swiss bank accounts. Writing about those accounts was one way in which my training and experience as a lawyer helped in setting the stage for the novel.

I have worked as a lawyer on cases involving numbered bank accounts. So, I knew those bank accounts were often shrouded in mystery and full of secrets, both in popular conceptions and in reality; as a result, those accounts provided an ideal setting for the secrets that any good spy thriller needs.

When writing the book, I needed to learn more about the history of those numbered accounts, as well as how they operated in practice – that included learning about the special banking laws that Switzerland adopted just before World War II and about how numbered bank accounts were handled by the banks and their clients.

More importantly, though, a thriller often also involves a different kind of law — on that’s less obvious, less technical, and more understandable than Swiss or other banking regulations.

Thrillers, like other literary genres, need a foundation of right and wrong, a moral compass. The heroines and heroes need to appeal to some higher values, beyond just surviving. With that in mind, in The File, main character Sara West insists that she wants just two things: justice and truth. She wants justice for her father and friends, who are brutally killed by Russian mercenaries (a version of the Wagner Group); and she wants truth about the secret Swiss bank accounts and those who helped the Nazis with their deposits. Sara’s uncomplicated sense of fairness, of justice, is another kind of law — one that is the opposite of the very formal, legalistic Swiss banking laws that hide the Nazis’ bank accounts.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say more generally that thrillers provide a way to explore these two varieties of law and how each of them produces — or doesn’t produce — fairness.

Toward the end of The File, Sara realizes the tidy streets of Zurich are in many ways more brutal and less civilized than the jungles and deserts she fled from, and that the cultured, wealthy bankers and businessmen on those streets are no more civilized or honorable than the book’s other characters. In the same way, the tidy banking regulations that permitted the numbered Swiss bank accounts concealed all manner of evil, while Sara’s straightforward sense of justice was the opposite, insisting on truth and fairness.

I don’t think that this view of law — The File’s view of law — is at all foreign to the lawyer work I do representing clients before courts and arbitral tribunals. No civilized tribunal or court ignores the sense of justice that drives Sara, including in cases where there is a formal or technical “law” that says the opposite.

Every lawyer has had experience with unjust laws and laws that are applied in ways that produce unfair results, as well as arguing that those laws should not be given those effects. Though my thriller isn’t about courts or judges, my experiences with the law, in countless different setting, played a major role in the book’s thrilling narrative.

***