The suspense and thriller genres are full of tales of kidnapping and captivity, but why do we love to read these stories? For that matter, why do we love to write about people deprived of their freedom and cut off from the outside world? From the harrowing and realistic (Still Missing by Chevy Stevens) to the far-fetched but terrifying (The Chain by Adrian McKinty), it’s obvious that the reading public is haunted by the notion of themselves or their loved ones being kidnapped and held captive. The prospect is so frightening that it easily crosses into the horror genre (Melanie Golding’s Little Darlings.) In no small part, I assume our fixation with such stories, as readers and writers, is born out of a deep-seated fear and an urge for self-preservation. If we read enough of these stories, we’re safe. It couldn’t happen to us, because we’re informed. Right?

What stands out to me most, as a reader and writer of suspense novels, is how starkly gendered these stories of captivity tend to be. It’s not that men don’t get kidnapped or imprisoned in real life and in fiction, but that it happens far less and for far less horrific reasons. From Rochester’s attic-imprisoned wife in Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre to contemporary heroines like the protagonist of Will Dean’s The Last Thing to Burn, womanhood is practically an oubliette. The slightest mishap and a woman can be thrown into a narrow chamber and forgotten by the outside world, like the little girls left to starve to death by Marc Dutroux, the murderous Belgian pedophile.

For men, the cornerstone of captivity stories is Alexander Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo. Wrongfully imprisoned in the isolated Chateau d’If, Dantès survives, escapes, and enacts his revenge. That’s what men do, after all: enact their revenge. (I’m looking at you, John Wick.) Dumas’ story is so enduring that two new cinematic adaptations of it were made in 2024, more than 175 years since it was first published. Men also get kidnapping stories like Graham Greene’s humorous The Honorary Consul and Robert Louis Stevenson’s iconic Kidnapped, whose plucky young hero escapes indentured servitude.

For women, things are not quite so … plucky. Although I confess I have not compiled the numbers, my general impression is that fictional tales of kidnapping and captivity feature female victims by a margin of a thousand to one. Perhaps those numbers represent a heightened fear among women of being kidnapped, but they almost certainly reflect the reality that women and female children are more likely to fall victim to kidnapping.

With bestseller lists topped by books like Emma Donaghue’s distressing Room and Gillian Flynn’s twisty Gone Girl, it’s clear that readers are fixated on stories of women in captivity. Unlike our fixation with dragons in fantasy, though, kidnapping stories are firmly rooted in reality. Men, in life and in fiction, tend to fall victim to kidnappings for ransom, and are more likely to negotiate their way out. Meanwhile, like their real life counterparts, women in stories of captivity are more likely to be abducted by dangerous men intent on fulfilling violent sexual urges or other deviant whims. (With the famous exception of Stephen King’s Misery, whose male protagonist is captive to the deranged demands of a female fan.)

Even in the thriller genre, works of fiction frequently bear the marks of real stories about real women and children torn from their lives and subjected to the unimaginable. In her novel Dear Miss Metropolitan, Carolyn Ferrell finds its real life echo in the twin memoirs of the survivors of the Cleveland Kidnappings: Amanda Berry and Gina DeJesus’ Hope: A Memoir of Survival in Cleveland, and Michelle Knight’s Finding Me: A Decade of Darkness, a Life Reclaimed. Lucy Christopher’s young adult novel Stolen and What’s Done in Darkness by Laura McHugh find their spark in the non-fiction section as well. Consider Jaycee Dugard’s A Stolen Life, Natascha Kampusch’s 3,096 Days, and I Choose to Live, the memoir of Dutroux’s last victim, Sabine Dardenne. The original French title of Dardenne’s book J’avais douze ans, j’ai pris mon vélo et je suis partie à l’école (I was twelve years old, I took my bike and I left for school) is an evocative testament to the sudden terror of being kidnapped as a child.

In keeping with the trend of women being kidnapped, this year’s Such Quiet Girls by Noelle W. Ihli fictionalizes the 1976 Chowchilla Kidnappings, but replaces the male bus driver with a woman. I sometimes suspect that this constant focus on women being abducted stems from male readers who have more faith in their ability to escape a kidnapper, and so are less willing to suspend their disbelief for a male kidnapping victim. After all, according to a YouGov survey, 7% of American men think they could best a grizzly bear in unarmed combat.

Eventually fiction does expand beyond fact, delivering multiple subgenres of kidnapped women. In John Fowle’s 1963 novel The Collector, we’re introduced to the idea of a man obsessed with a woman to the point that he chooses to kidnap her and keep her as a prized possession. That sixty-year-old novel provides a launching point for such books as The Cellar by Natasha Preston and by Dot Hutchison’s The Butterfly Garden, which seems determined to ramp up the concept to an unhinged level with more than a dozen collected victims.

Although it’s outside the purview of this essay, there is even a subset of the dark romance genre that focuses on kidnapping victims falling in love with their captors. As much as we might wish this were entirely outside the realm of possibility, we have to consider the long tradition in cultures all over the globe of marriage by abduction. It has passed away in many cultures, but there are still places where women and girls are forced to marry their abductors, bear their children, and keep their homes. In telling those dark romance stories, contemporary fiction converts the old horrors of womanhood into the new horrors of womanhood.

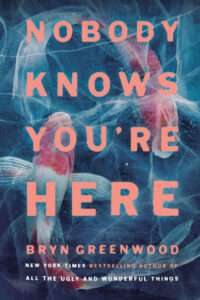

If we read these books to somehow prepare ourselves for the way they intersect with reality, we write them because we still have things to say about our fears. When I wrote my newest novel, Nobody Knows You’re Here, I wanted to discuss the mundane ways in which people are abducted. Being stolen off the street is far less common than being prevented from leaving a place you went to voluntarily. There are more nefarious people looking to force victims to do unpaid labor than there are psychopaths looking to lock women in their sheds. Recent statistics suggest that of those trapped in modern slavery, 54% are female and 46% are male. At least in the area of human trafficking, men and women are on more equal footing.

***