During my 19-year career as an investigative reporter for daily metropolitan newspapers, I always approached stories with an open mind. Today, as the New York Times bestselling author of 16 books, most of them narrative nonfiction crime titles, that hasn’t changed.

Although sometimes an editor would assign me a story idea, I purposely would try not to begin my research with preconceived notions, because they often proved wrong. I often went into the story looking for holes in what everyone thought was true, for answers to unanswered questions. If I let myself be open to new ideas, they would usually come to me—and they were often more interesting than what the editors had suggested. So, they came to trust me: “You’ll find it,” they said. “Do your thing.”

Today, that approach is front and foremost in my mind when I start researching a story. I’m not just looking for basic facts, I’m looking for back story—of the victim, the killer, the investigation and the trial, the emotional, political or financial motivations of everyone involved. Because those usually aren’t found in a brief news story or a short TV docu-style show, none of which go very deep. That is my job, the deep dive.

As an author in a crowded marketplace, where people think they have already heard the whole story on TV, online or in the newspaper, that new information can advance the story, surprise and impress the reader, and keep them turning pages. More importantly, it keeps them buying my books so I can afford to keep writing them.

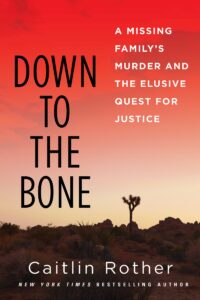

I also look for other interpretations of evidence from what police investigators and prosecutors present to the jury, especially in a case where the defense argues that there was confirmation bias. That is when investigators focus on one premise, theory, or suspect and ignore or dismiss any evidence that does not support their original idea. That was the victim’s family’s position about the sheriff’s investigation in my last book, DEATH ON OCEAN BOULEVARD, about the mysterious death of Rebecca Zahau, and that was the defense’s position in my newest release, DOWN TO THE BONE, about the McStay family murders, which comes out on June 24.

Sometimes, what draws me initially to a story doesn’t pan out or isn’t enough to write a compelling book. But sometimes, as I get deeper into my research, a story gets even better and more complicated than I expected it would be.

That’s what happened with DOWN TO THE BONE. The deeper I went, the messier this case became, the more twists, turns and surprises I encountered. I really believe that readers will be surprised to learn the behind-the-scenes story of how this case, about the murder of a family of four, including two little boys, from Fallbrook, California, progressed to trial and to a death sentence for Charles “Chase” Merritt.

A story has to ring a number of bells for me to hold my interest—and the reader’s as well. I often write stories that involve more psychological themes, such as addiction, mental illness and the manipulations of financial conmen/women rather than violent mass murders or serial killers. This one drew me in because it involved a pretty complicated mystery, two flawed investigations, and a prosecution that got a guilty verdict despite contradictions in its evidence and timeline and left many important questions unanswered. But I didn’t know all that when I started.

The more complex and interesting the characters are, the better, because I don’t see the world in black and white. To me, it’s a lot of gray. I gravitate toward accused killers who are not single-mindedly bad people, but those with interesting lives and complex motivations that make them three-dimensional people, some with traumas of their own.

Because we all want the answers to these questions: Why do they kill? What happened in their lives to make them this way? How much was genetic or environmental and how much was due to choices they made? Or is it possible that the accused person is not the killer at all?

I don’t want to give away my trade secrets in how I research, so I will keep it general. In the past, I always picked the low-hanging fruit first—the news stories, the court files, the public information that was previously easy and plentiful to access. However, times have changed.

Today, media outlets have paywalls, there are far fewer reporters (and photographers) who cover trials, and when they do, they usually only cover the opening statements, closing arguments, the verdict, and sentencing. Also, most of the experienced veteran journalists like me have left the business long ago, taken buyouts, been laid-off, or moved into PR, so the stories are often short and superficial. That means, I have to be more creative, to dig even deeper.

Court files aren’t the treasure troves they used to be either, because in California, the governor has changed the landscape to allow criminals to be rehabilitated and get jobs, so the court files have less in them these days, and what was once in there, is removed after a set period of time.

In addition, some law enforcement agencies and DA’s offices, which will go nameless for now because I don’t want to make things worse for myself, have gone into CYA mode. They don’t return calls or emails and they don’t want to be transparent. So, all of this makes a true crime author’s job much harder.

I am grateful that I am experienced now to know what materials I need and can go after them even if they are difficult to obtain. For my latest two books, I was not able to obtain interviews with a key character or crucial written documents and discovery materials until the last minute before my deadline. That required me to rewrite both books under extreme time pressure, but I do what I have to do to make my books the best they can be.

__________________________