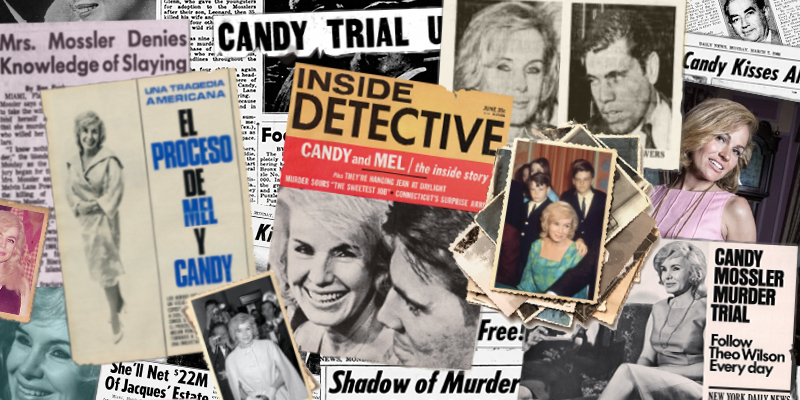

In early 1966, a midair crash involving two U.S. Air Force planes set loose an unexploded hydrogen bomb somewhere near the coast of Spain. For the next several weeks, the U.S. military’s all-out search for the nuclear device was the subject of constant press coverage. But it was not the biggest story in America. That distinction, remembers renowned journalist Lewis Lapham, belonged to a murder trial being held in a downtown Miami courtroom. “The story of the United States losing an atomic bomb,” says Lapham, shaking his head in astonishment, “got second billing to Candy and Mel.”

Candy and Mel. The names may not resonate the way they once did, but the aftershocks of the trial of Candace Mossler and Melvin Lane Powers are still being felt. While it was not America’s first tabloid trial, the way it transcended the tabloids was notable. It was featured in publications normally not associated with the scandalous or salacious, including The New York Times and Time magazine. On newsstands, it competed for attention alongside the Beatles.

And it was a magnet for television. The trial became a spectacle like few had witnessed: the first true-crime story of the modern media age, or, if you prefer, reality TV before the concept had a name.

But before the trial, there was the murder.

At approximately 4:30 a.m. on June 30, 1964 — 60 years ago this month — Candace Mossler, a former model-turned socialite, returned to her husband Jacques’s apartment in Key Biscayne to find his body on the floor, wrapped in a thin orange blanket. He had been bludgeoned and stabbed. The crime was shocking both for its excessive violence— there were 39 stab wounds — and for the identity of the deceased. Jacques Mossler, age 69, was one of the richest men in America, a pioneer of the postwar consumer credit boom whose personal fortune was estimated at $30 million, or about $300 million today. Men like Jacques Mossler did not routinely turn up murdered, and certainly not in a place like Key Biscayne, an exclusive island community near Miami later famous as the winter residence of Richard Nixon.

Detectives quickly narrowed the list of suspects to two: Candace and her 22-year-old nephew, Melvin Lane Powers. Mel had moved into the Mossler mansion in Houston in 1962, when his mother, Candace’s sister, had asked the Mosslers to take in the troubled youth. Jacques gave the tall, strapping Mel a job at one his companies. Candace, a stylish blonde who was still youthful at 44, liked to take him around and introduce him to her society friends. What became apparent — eventually, even to Jacques — is that Candace’s interest in Mel was not solely that of a caring aunt. At some point, Mel and Candace had begun an incestuous affair.

When Jacques found out, he evicted Mel from the mansion and, looking to distance himself from the whole tawdry mess, relocated to Miami, where he owned several businesses. That was in October 1963. Eight months later, Candace brought their children for a visit. Somewhat conveniently — too conveniently for police — they were all away from the apartment when Jacques was murdered.

Police determined Mel had flown from Houston to Miami only hours before the murder, and had returned to Houston in the immediate hours following the crime. Furthermore, there were witnesses who could place Mel near the crime scene. Around 10 p.m. that evening, he had been spotted at the Stuft Shirt Lounge, a bar on the Miami side of the Rickenbacker Causeway leading to Key Biscayne. According to witness testimony, he ordered a scotch and asked for a large, empty, glass Coke bottle. He left the bottle behind. Two hours later he returned to the Stuft Shirt, ordered a double scotch, and asked for another Coke bottle. Investigators surmised Mel might have been drinking to screw up his courage, and that he had used the second bottle to bash in Mossler’s head before stabbing him.

Other discoveries included a handprint belonging to Mel found in Jacques Mossler’s apartment, bloodstains on the clothes Mel reportedly wore to Miami, and a white Chevrolet abandoned in a parking lot at Miami international Airport. The car, which contained Mel’s fingerprints and matched the description of the vehicle neighbors saw leaving the crime scene, turned out to be a loaner belonging to one of the Mossler companies. It had been last checked out to Candace.

To prosecutors, it seemed obvious: Candace and Mel had conspired to kill the old man for his money. A warrant for Mel’s arrest was issued on July 3, the same day Jacques Mossler, a World War I veteran, was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

The case against Candace took longer to build, but she too was arrested. That event took place at Miami international Airport, with news cameras rolling. “Mrs. Mossler, you have been accused of incest, adultery, and murder,” began one of the newsmen, shoving his microphone into Candace’s face. “What would you like people to know about you?” Candace’s reply was, in its own way, as explosive as that H-bomb the U.S. military would soon be looking for: “Well, sir, no one is perfect.” The Candy and Mel show had begun.

(She hated that name — “Candy” was so déclassé — but it was the one the press pinned on her, and she would wear it from then on.)

The attorneys involved in the case would only add to the allure of the trial. When Mel was arrested, Candy hired famed Texas defense attorney Percy Foreman to defend him. A large, imposing man who wore his hair slicked back, Foreman was a legendary trial lawyer who had litigated hundreds of murder cases and, by most accounts, lost only one. Foreman liked the spotlight — a few years earlier, he had been briefly retained as Jack Ruby’s defense attorney after Ruby shot and killed Lee Harvey Oswald — and had a down-home manner that was both charming and ruthless. He was known to boast that he preferred trying murder cases because there was “one less witness.”

Candy’s defense featured the Houston-based legal team of Clyde Woody and Marian Rosen. The latter was a rarity at the time: A prominent woman lawyer. Rosen was strikingly beautiful — and as sharp as any man in the courtroom. The last surviving attorney to have worked the trial, she recalls the defense team’s first hurdle. “Let me just cut to the chase,” she says. “We did not want women on the jury… because female jurors, as a rule, are very harsh on female defendants. They really scrutinize them carefully, find fault with any little thing, whether it’s their clothing, their makeup, their demeanor, their dress. Whatever it is, they’re going to find fault with it. So we really wanted an all-male jury.” A wrinkle in Florida law — women were excluded from being called for jury duty unless they opted in — made this fairly easy. Rosen got her all-male jury.

By the time the trial got underway in January 1966, journalists had spent a year-and-a-half reporting on the murder of Jacques Mossler and the revelations that had come to light in its aftermath. With the main event finally at hand, the appetite for all things Candy and Mel only intensified. The New York Daily News, sensing a circulation builder, sent noted crime reporter Theo Wilson to Miami to file daily dispatches. “Candy Mossler Murder Trial — Follow Theo Wilson Every Day,” advised a poster that showed Wilson, notebook and pen in hand, sitting side-by-side with Candy on a sofa. The image of the two women (“Theo” was short for Theodora) was plastered on subway cars and the sides of Daily News delivery trucks for weeks.

“You had a case that involved sex, money, blood, and that was going to draw a lot of media attention,” says Rosen, adding that, of course, “people really enjoyed the sexual angle.”

Someone who did not was presiding judge George E. Schulz. He declared that, owing to the graphic nature of some of the testimony, no one under 21 would be admitted. Naturally, this only had the effect of fueling the public’s fascination with the trial; hundreds of spectators lined up daily outside the Miami courthouse as early as 5 a.m., hoping to nab a seat in the courtroom. The two dozen or so seats reserved for the media were no less coveted.

Interest in the trial reached a fever pitch and stayed there. “It was not uncommon for Candace Mossler to be on the front page of a newspaper somewhere in the world every day during this trial,” says Ron Smith, author of No One Is Perfect: The True Story of Candace Mossler and America’s Strangest Murder Trial. “In fact, it was said that only Candace Mossler could knock Jackie Kennedy off the front page.”

Though television cameras were not allowed in courtrooms at the time, networks and local stations were able to capture Candy and Mel’s comings and goings. Often, Candy would stop to share her thoughts on the proceedings in a breathy voice that conveyed equal parts sex appeal and defiance. Once, says Smith, “she actually convened a reception for the media at her hotel suite.”

Normally, making a defendant in a murder trial available to reporters would be considered professional malpractice by a lawyer, but Rosen knew exactly what she was doing: “Candace was well spoken. She was beautiful. She was charming. She knew how to handle herself. And gradually it became evident that she was really great with the reporters. They loved her quips, and the way she approached things. She was a fighter. She was not going to be cajoled into anything.”

While Candy wooed the media outside the courtroom, the defense focused on overcoming the prosecution’s case. Dade County State Attorney Richard Gerstein seemed to be holding all the cards. The prosecution had the motive (a $30 million fortune), it had significant physical evidence (the handprint in the apartment, the fingerprints in the car), and it had the couple’s demonstrated moral depravity (their incestuous relationship).

Prosecutors seemed to revel in the details of Candy and Mel’s relationship, among them, Candy’s supposed predilection for (receiving) oral sex. One witness for the prosecution told the court that Mel once claimed Candy was pregnant with his child. (Sitting in the courtroom, Candy gasped — then smiled at the jury.) The prosecution also produced a parade of ex-cons and jailhouse snitches who testified that, at various times, they had been approached by Candy and Mel about killing Jacques Mossler. It was potentially damning stuff.

But the defense team was unshaken. This trial was about a murder the state claimed Mel Powers had committed. And for all the so-called evidence tying Mel to the crime, there was no witness who could actually place him in Jacques Mossler’s apartment on the night in question. And what about the supposed murder weapon? No knife — or, for that matter, a Coke bottle like the one Mel allegedly had removed from the Stuft Shirt— was ever found. No, the defense argued, the prosecution was going to have to do better than that.

Foreman had an alternate theory of the crime, which he happily shared with the jury: Jacques Mossler had built his business on predatory lending and loan-sharking; he had destroyed countless individuals by driving them into debt. And he was not the family man people imagined. Rather, Mossler had been leading a double life as a closeted gay man who would routinely invite sexual partners into his home, then discard them. Summing up his portrait of Jacques Mossler, Foreman offered that “if each one of those 39 knife wounds on Mossler’s body was inflicted by a different person, there still would be many times that number of [possible suspects].” If that didn’t constitute reasonable doubt, Foreman asked, what did? After seven weeks, the trial went to the jury.

“I think we had a few on the jury that thought they were guilty,” relates former juror Fred J. Zoller. “Maybe half of them weren’t sure.” After two days of deliberations, the jurors informed Judge Schulz they were deadlocked. The judge instructed the twelve men to keep trying. Following another long day, they had unanimity, or something like it. “I think a lot of [the jurors] didn’t want to stay there; they were getting tired,” says Zoller, then a post office worker who, unlike some of his fellow jurors, was enjoying the time away from his job.

On Sunday, March 6 — the timing caught even Judge Schulz off guard — the jury came back and announced it had reached a verdict. After everyone had hastily convened in the courtroom, it was read aloud. Not guilty. The photographers who were in the courtroom began yelling for Candy and Mel to kiss. (Wouldn’t that make for a memorable front page?) Instead, Candy went over to the jury box and kissed the jurors. “Yeah, she said ‘Thank you,’” remembers Zoller, who adds that he came to his verdict honestly: “I went by the evidence.”

Some would later fault the prosecution’s decision to try Candy and Mel together; the theory being that it would not have been that difficult to convict the hulking, brooding Mel of the crime, but that, when his fate was tied to Candy’s, that made it much tougher, because to find him guilty, the jury also had to find her guilty.

For Lapham, who covered the trial for The Saturday Evening Post, it was less complicated than that. “Percy [Foreman] told a far better story and told it… in a way that the prosecutor could not match,” he says. Not necessarily a true story, mind you, but a better one.

After leaving the courtroom, Candy and Mel jumped into a gold-colored Cadillac convertible that had been strategically positioned outside the courthouse. With Clyde Woody at the wheel, the couple, accompanied by Rosen, rode off into the future: in Mel’s case, a decades-long career as a Houston developer; in Candy’s, marriage to a man whose luck was no better than Jacques’s. That husband, Barnett Garrison, suffered brain damage following a mysterious fall from the roof of the couple’s three-story home. (He spent the last 25 years of his life in a nursing home.)

For Candy, the end came in 1976, when she traveled to Miami for a meeting of her bank board — one of the businesses she inherited from Jacques — and was found dead in her hotel room, the victim of an apparent overdose of painkillers and sleeping pills. In what can only be called one final plot twist… she was buried beside Jacques at Arlington National Cemetery.

When Mel died in 2010, The New York Times referred to him as one-half of what was likely “the nation’s most notorious couple” in the mid-1960s. But that designation doesn’t quite seem to capture the cultural significance of Candy and Mel, or the sea change they helped usher in.

“Can you imagine what the trial of ‘Candy and Mel’ would look like in today’s world?” speculates Smith. “It would be off the charts. Everyone would be keeping track of it on their phone. CNN, Fox, everybody would make it the lead story of the day. I mean, given Candace’s propensity for cameras, she would have invited us right into her house.” In a way, she did.