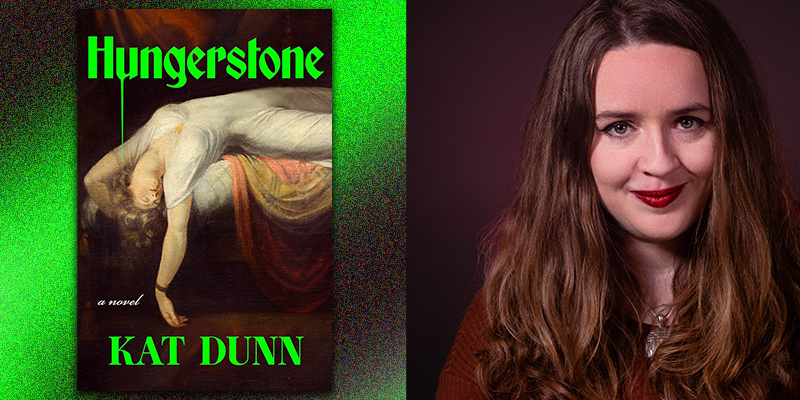

I am OBSESSED with Kat Dunn’s debut, the delectably carnal and unabashedly queer vampire novel Hungerstone, and not just because of that gorgeous cover design. Hungerstone is a re-envisioning of the vampire classic Carmilla, in which a Victorian wife’s meticulously ordered world comes apart at the seams when a strange, pale woman comes to visit and awakens hitherto hidden desires: for love, for vengeance, for flesh, and most of all, for an end to bourgeois boredom. Kat Dunn was kind enough to answer a few questions over email.

MO: Can you tell us about the inspiration for your novel? What’s the place of Carmilla in vampire history, and how did it languish for so long in obscurity?

KD: Carmilla was written by Sheridan le Fanu about twenty years before Bram Stoker wrote Dracula. Le Fanu was a well regarded, popular writer in his era, and much of his work, like Carmilla, was published in magazines. There’s been lots of discussion and research into where Le Fanu drew inspiration for Carmilla, but it formed a foundational part of both the gothic, and vampire, literary canon. I don’t know why it’s less well known than Dracula, but perhaps Dracula, ostensibly more ‘straight’, at least, on the surface, leant itself better to adaptation on film in the 20th century.

MO: Is the vampire an inherently queer figure?

MO: Is the vampire an inherently queer figure?

KD: I think you could make that case! The vampire, and gothic horror in general, is so rooted in fear of—and attraction to—otherness, transgression, fracturing societal norms and control. I think there’s quite a large and complicated conversation you can have about how queerness was used in texts like Carmilla and Dracula, what any original intention or interpretation might have been, but nevertheless the vampire as outsider, as other, as misunderstood hero, as seducer, as fantasy or fear, remains a hallmark of queer media.

MO: How did you go about writing desire in your novel?

KD: Through Lenore I wanted to explore a character who moves from an extremely controlled state where the problem of desire is solved, suffocated, buried, to one where desire cannot be denied, and all the terror of disappointment, of exposure is laid bare. At the start of the novel, Lenore is an entirely mastered person, believing herself to be in control of her emotions, of the world around her. She has no vulnerability, no place in which she is exposed. She can be the perfect society wife, cope with any challenge, need nothing—it is only in food where this lie is exposed. She binge eats, and is hyper-aware of her husband Henry’s disgust at her appetite. Through the arrival of Carmilla, Lenore is forced to confront that her appetites, her desires, might be far larger, far more complex. Lenore desires Carmilla sexually, but she also longs for her company, her approval, and longs to be like her, uncowed, expansive, entirely true to herself.

MO: There are so many books coming out concerned with women’s appetites—it seems that to eat is a bigger sin than to kill. What did you want to say about appetite, cravings, and bodies with Hungerstone?

KD: I was interested in exploring a literal hunger as a metaphor for the way desire can become confused and obfuscated, and solved, instead, through a different, more base hunger.

Carmilla says at one point, ‘You are feeding the wrong hunger.’ I was interested by the idea that our desires can often be so large, so frightening, so impossible to fulfil, or the disappointment in not having them met so threatening, so exposing, that we cannot face them dead on and instead turn to a more physical appetite that seems a simpler way to sate an appetite. We might not be able to control whether our desire for love, acclaim, justice, revenge is fulfilled—but we can control food, and our bodies, so our hunger shows up there instead. But of course that then can be monstrous and judged in and of itself—our appetite for food is where we are exposed as creatures of want, of desire, and that for women can be a sin in itself.

MO: What do you think is behind the vampire revival in fiction? Did it just take a while to get over the embarrassment of Twilight?

KD: I don’t think anyone has to be embarrassed by Twilight! I wasn’t a fan, personally, but there’s no shame in enjoying things, and I don’t think it would be very in keeping with the gothic to shame people for what they are drawn to. Perhaps it’s just that we’re far enough away from a dominant portrayal of vampires that there’s space for new takes to emerge. The struggle with the darker, less controlled, more feral side of our natures is an innately human thing, and is a question we will always come back to.

MO: Do you consider your novel gothic? Why are we so intrigued by gothic tropes at the moment?

KD: I definitely had the gothic literary tradition in mind as I was writing Hungerstone. I think the gothic is a perennial for exactly the reasons I’ve already explored—the desire for and horror of otherness, of transgression, of rejecting and defying norms, all speak to deeply to something deeply huma

n in us, something we are drawn to and frightened of—and to externalize it as something supernatural, something unreal, gives us a fig leaf of plausible deniability so we can look at and enjoy something we can in the rest of our lives safely tell ourselves that we reject.

MO: Why did you decide to set your novel in the moorlands? What is it that is so evocative about the setting?

KD: The moors are such a classic gothic setting, offering a barren, challenging wildness that is at once so exposed and open, and yet so hostile to comfort. Writing a close first person narration, you spend a lot of time interpreting the world of the book, its events and all the characters in it through the opinions and prejudices of the main character, and setting—whether the moors of the Peak District or the crumbling Nethershaw estate—give an opportunity to reflect and show a different interpretation of things, to reveal something about our main character that they might not notice themselves.