As the great Jim Thompson said, “There is only one plot – things are not as they seem.” And it still holds as true today as it did for Jim, and even well before him.

So who’s Jim Thompson? I hear some of you ask. (Hopefully not too many of you, because if that’s the case, we really may not be able to be friends.) In short, the greatest American writer of noir in the Twentieth Century. A bold claim, but one that even a cursory dalliance with his work will bear out. ‘Read Jim Thompson and take a tour of Hell’, the quote on the back cover of so many of his novels used to scream out. And that’s the truth. He wrote for the paperback original market, those small books that could fit into the back pocket of a pair of Levis, full of dangerous dames and hapless weak men, they were sold at newsstands and on spinner racks in drugstores. Thompson wrote about losers, men at the end of their tether, the downtrodden, the amoral and desperate, and the women who came into their orbit. Usually to take advantage of them, often terminally, and earned himself the soubriquet ‘The dime-store Dostoyevsky’.

You probably know some of his novels, even it’s just from the film versions: THE GRIFTERS – a twisted oedipal tale of con artists and betrayal, THE KILLER INSIDE ME – a portrait of a serial killing sheriff of a small Texas town, or THE GETAWAY, in which a modern Bonnie and Clyde try to escape from the mob, killing their way, figuratively and literally, into Hell. And yes, the stories are all different, but the plot – things are not what they seem – is the same.

At first when I read that I thought it was only applicable to a certain type of mystery novel and was quite dismissive of it. But I started to think about it more. And, as with so many things literary-related, old Jim was right. Drama, as theatre director Peter Brook once said, is conflict. And he’s right. No one wants to read a novel or see a play where people are happy and well-adjusted and nothing happens to disrupt their well-ordered lives. That’s boring. But what if their well-ordered lives are built on a lie? And a narrative wrecking ball is swung at them, exposing that lie? What then? Well, then you’ve got a story. You’ve got conflict. And you’ve got the one basic plot: Things are not what they seem.

We see it mostly in crime fiction. In fact, crime fiction not only thrives on it, but is built around that maxim. That’s why detective stories are so popular. Now, your detectives can come in any stripe: hard-boiled, cosy, whatever. Even cats can solve crimes. The one thing they all have in common is not taking a situation at face value and seeing beyond that. Whatever carefully constructed facade has been erected is demolished by them in their pursuit of the truth. Because (all together now) things are not as they seem.

Spy and espionage stories are the same. In fact, it’s inherent in their nature even more so that crime novels. Their whole existence is built on lies and fabrication, on illusion. No one trusts any one. No one knows any one. It’s a fascinating genre to explore. And I’m not just saying that because my next novel takes place in that genre. Every decent spy story asks us questions about who we are, who we think we are, how we see ourselves, how we’re perceived by others. And, of course, who we really are. If we can be known at all, that is.

The very specific area of this I want to look at is the twist. Yes, I know it’s a hoary old staple of the genre, often dismissed by some critics (and readers too) but in all honesty, pulling of a major twist is an art in itself. Remember Clarice Starling in THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS? She’s been sent on some wild goose chase, doing menial work, tracking dead ends, while Jack Shepherd leads a SWAT team to take down Buffalo Bill at the address they have for him? Except – twist! He’s behind the door Clarice knocks on! I actually gasped out loud when I read that. And watching the same scene in a cinema, I can attest the audience did as well. The fact that I’ve nicked that twist for my own books a few times is neither here nor there. I’m not proud.

In fact, some of the greatest films of the last few decades have proved this point perfectly. Take, for instance, THE USUAL SUSPECTS. Surely we all know the story now, don’t we? Verbal Kint, the lone survivor of a shoot out, is brought in for questioning. A small, unimposing man with a limp, he starts telling the burly Detective Kujan the story of what happened, including the whereabouts of the master criminal Keyser Soze. And we follow the film as that story unfolds. And it is a story. Because Verbal has made the whole thing up from looking at things on the board behind Kujan and from other things in his office. In possibly its most memorable sequence, Kim walks free from the station and the camera remains trained on his limping feet as they gradually give way to a non-limping gait, then a stride. Back in the office Kujan, looking around, realises what’s just happened and that he let master criminal Keyser Soze, escape from his grasp.

The film makes the viewer question what they’re being told and what they’re being shown. It sets up its premise as being real and invites us in and then, by the end, that’s all been upended and we realise that we, the audience along with Kujan, have been conned. And the thing is, unlike Kujan, we don’t mind. Because while we’ve been told what amounts to pack of lies, we’ve been right royally entertained in the process and all we can do at marvel at how we were willingly sucked in.

I love this kind of storytelling. Where there’s a narrative rug pull and you realise nothing you’ve been told and everything you’ve invested in, is true. It’s THINGS ARE NOT WHAT THEY SEEM writ in massive, illuminated letters that can be seen from space. It’s also the hardest kind of thing to write. Or at least it’s one of the hardest things to write properly. Anyone can stick a cheap twist in a narrative that no one could see coming and hope the reader or viewer is surprised by it. That’s just hack work. To make a twist of the USUAL SUSPECTS variety work, a proper, brilliant, game-changer of a twist, it has to appear organically from the narrative and not leave the audience feeling conned or short-changed.

Another great example of this is another movie from around the same time (there must have been something in the zeitgeist). THE SIXTH SENSE. I don’t think I’m spoiling anything by telling you the twist of a twenty six year old film when I say, Bruce Willis was a ghost all along! And if I have ruined it for you, I sincerely apologise. But here’s the thing. The twist in that film is so great that even knowing what’s coming, you can still watch it again and be entertained. Not in the same way, obviously, because you can only experience that shock once. But in another way. A knowing way. Because the film plays so straight and uses the twist so well that it stands up to repeated viewing. In fact it encourages it: watch it again knowing what’s going on and it makes perfect sense. And it holds up. Because events we assumed were playing straight the first time (for instance, when we first see Willis sitting with the boy’s mother in separate armchairs we assume they’re just not talking, but then on a second viewing we realise she’s siting there alone with her grief) are then, in the audience’s understanding, even though nothing specially has changed on the screen, experienced from a different, more knowing, narrative perspective. This is what I mean when I said earlier that the twist must arise organically from the material. It should be earned. And if it isn’t, the audience, the readers, will hate the writer for it and think they’ve been made a fool of.

Which leads us to possibly the best example of this: SHUTTER ISLAND. Both the novel and the film. I read there novel knowing nothing of the twist or indeed what it was about. I ignored the reviews – deliberately – and went in as cold as I could. The least I knew the better. And it worked. God, did it work. I was completely sold. I believed Teddy Daniels was an FBI agent investigating a patient’s disappearance on Shutter Island. Why wouldn’t I? And when the twist came I felt like I’d been slammed into a wall. In a good way, obviously. Consequently I went into the film knowing what was going to happen and, like with a rewatch of THE SIXTH SENSE, it played it straight. Possibly too straight: No one could be fooled by this, I thought, could they? Course they could. I was.

William Hjortsborg’s occult private eye novel, FALLING ANGEL, concerns a private eye searching for a missing crooner at the behest of a mysterious client. Of course – twist! He’s been hunting for himself all along and the mysterious client is the Devil, who he’s sold his soul to. Memorably made into a film, ANGEL HEART, by Alan Parker, Mickey Rourke looks damaged, lost and impossibly handsome in that. There’s no indication of the fey Ernest Borgnine lookalike he would eventually transform himself into.

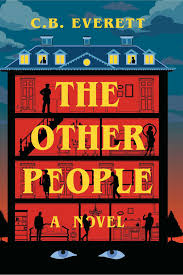

Which I guess leads us back to me. My new novel, THE OTHER PEOPLE, under my new name CB Everett, is about to be released. If you like the kind of books and films I’ve been talking about here, chances are you’ll like my novel too. It starts with ten strangers having been invited for dinner in a mysterious old, dark house. In order to leave they have to solve the mystery of a missing young woman. But there is also a murderer in the house with them – or could it be one of them? – picking them off one by one . . .

Sounds like an old story? Maybe. Think you’ve heard that before? Read it before? Seen it before? Yeah. No. You haven’t. Remember, there’s thirty two ways to tell a story, and, like Jim Thompson, I’ve used all of them. But there’s only one plot. It’s the best one ever, and that’s the one I’ve used here.

Things are not what they seem . . .

***