Art imitating life is hardly a new idea. The ancient Greeks did it, Shakespeare certainly did it, and any number of writers and film-makers have been doing it ever since. And when it comes to crime, real life offers a particularly fertile seam of potential plotlines. There are hundreds of examples—from Murder on the Orient Express (which drew on the infamous Lindbergh case) to Gone Girl (where elements of the plot echo the 2002 murder of Laci Peterson); from The Silence of the Lambs (which amalgamated details from three different serial killers) to Psycho (inspired by one of those three, Ed Gein). As for TV, the list is even longer—in fact, there are so many examples in the Law & Order franchise that one UK cable channel recently ran a whole season under the banner “Ripped from the Headlines.”

So far, so unsurprising. But when it comes to the relationship between fact and fiction, contemporary crime boldly goes where most other genres rarely venture. It’s not just the fact that books and TV create (more or less disguised) storylines “inspired by” particularly heinous or arresting real-life cases. That happens all the time, but what I’m talking about here is a much bigger deal, and a much more interesting phenomenon: the evolution of whole new narrative tropes.

***

“Trope” has become something of a buzzword lately (as has its close relation “meme”), so let’s start by nailing down what I actually mean. The conventional dictionary definition of trope is “a significant or recurrent theme; a motif.” And that’s right, it is. But in recent years the word’s meaning has both widened and deepened, so that “tropes” are no longer just a recurring theme or plot device but function as precise and sophisticated signals to the reader or viewer. In other words, as the TVtropes website helpfully puts it, tropes have become “devices and conventions that a writer can reasonably rely on as being present in the audience members’ minds and expectations.” And if you’re wondering why they’re so prevalent in crime narratives the answer is right there: crime in all its forms taps into the darkest recesses of our minds, leaving us wide open to the skillful manipulation of tropes that play on our shared and often unacknowledged fears.

There have been terror tropes as long as there have been humans, of course. Bogeymen and baby-snatchers and monsters under the bed are common to cultures across the world. What’s different now, I would contend, is how uncommon the crimes that spawn these new tropes are. It’s the outliers, the one-in-a-million murders, the scarcely credible cruelties, which are becoming the stuff of our collective nightmares, and one of the most recurrent and resonant of these is the “cellar captive.”

It was Lord Byron who said that “as to originality, all pretensions are ludicrous—there is ‘nothing new under the sun.'” And yes, in that sense there’s nothing “new” about abduction and imprisonment as a narrative device, from fairy tales like Rapunzel, right through to a novel like John Fowles’ haunting The Collector, where the butterfly-obsessed protagonist abducts a young woman and keeps her in a specially adapted cellar. The book made a lot of waves when it was first published in 1963, precisely because the premise was so extra-ordinary, so unlike anything that might happen in “real” life—the New York Times, for example, called it “bizarre.” Even though a number of notorious serial killers have since claimed their crimes were inspired by the book, the idea of “imprisoning women underground” (which Fowles admitted was one of his own fantasies) remained a one-off, a singularity, “bizarre.”

But in 2008 all that changed. Because that was the year the world found out about Josef Fritzl. A man who’d held his own daughter captive for 24 years in a specially constructed basement below the family home, repeatedly raping and abusing her, and fathering her seven children. A few months later, in California, Jaycee Dugard was released from 18 years of captivity at the hands of Phillip Garrido, who’d kept her and the children she bore him hidden in a barricaded back yard. And then in 2013, three young women were finally freed from the Ohio home of Ariel Castro, where they’d each been locked in upstairs rooms for up to a decade.

There have been others, but these are the stories that have burned themselves into the public imagination; these are the stories that turned barely believable fact into constantly recurring fiction. We’ve had Emma Donoghue’s impressive and immersive novel Room, Chevy Stevens’ Still Missing, Carla Norton’s The Edge of Normal, Elizabeth Scott’s Living Dead Girl, Lucy Christopher’s Stolen, Lisa Jewell’s Then She Was Gone, Emma Rowley’s Where the Missing Go, and Natasha Preston’s The Cellar, among many others (and no, I don’t think it’s a coincidence that all the writers I’ve listed are women). As for the screen, there’s been the BBC’s drama Thirteen, and a whole season of The Missing, both based on the same premise, alongside films like Atom Egoyan’s The Captive, and more recently, M. Night Shyamalan’s Split, as well as – needless to say – more than one run-up at the same theme in Law & Order: SVU.

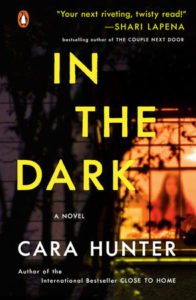

All these writers know about Fritzl and Garrido and Castro, and even more importantly, they know we know. That gave Donoghue the freedom to flip the perspective and take us inside the mind of an incarcerated child who’s never known another reality; it meant Thirteen could turn the spotlight on the victim and explore issues of cause and complicity; and it allowed The Missing to question whether the person who came back was even the same person who went away. And I’ve done exactly the same thing myself, in In The Dark, where a girl and her child are found locked in the basement of a house on a genteel Oxford street. Because that idea has become such a powerful and pervasive trope, I know my reader will bring a whole array of assumptions to that mise-en-scène which I can explore, manipulate, and—perhaps—subvert.

***

Every time I go to a crime festival, there’s always someone in the audience who asks why this type of book is so popular. And it’s a damn good question: why are we all so keen to bring death and violence into our imaginations, when we’re only too glad that it almost never intrudes into our actual experience? And tropes like the cellar captive are even more extreme versions of the same phenomenon: a crime like this is vanishingly rare in real life so why has it become so endemic in fiction? Why do we never tire of watching it and reading about it? Why, and why, and why again.

There’s one easy answer, and that’s shock value, pure and simple. But I think there’s more to it than that alone. The basic concept of the “captivity narrative” dates back centuries, and has taken many different forms in that time, with Gothic novels being perhaps the most obvious example (persecuted and imprisoned heroines, dark sexual predators, secret dungeons, need I say more). Contemporary urban imprisonment stories draw their power from all those cumulative layers of association, and the best of them do so entirely consciously, using the trope to examine the shared fears it evokes, and the questions it provokes: the balance of power between the genders, the human capacity to survive, the emotional and psychological consequences of extreme isolation, and how the psychopaths who commit these crimes can move among us in plain sight. As Josefina Rivera puts it in her 2014 account of her own abduction, Cellar Girl:

If you looked at him, you’d never imagine for a minute he was any different from you. Until you’ve met someone like Gary [Heidnik] you can’t even imagine another human acting this way. Then, when you have, you realize that everything you thought you knew could be false.

Like many survivors of real-life predators, Rivera wrote her story as part of the process of recovery, and to justify the decisions she made in an effort to survive (“I want to set the record straight”). But however valuable they might be for the writer, memoirs like this often struggle to offer resolution to the reader, because so many questions are left unanswered. Criminals like Fritzl or Castro or Heidnik rarely apologize and seldom explain— they don’t talk about their motives, and even if they do, those motives often don’t “make sense.” And that’s what fiction can do. Because—as Tom Clancy famously said—fiction does have to make sense, and it has to offer answers as well as questions. And the first and most important of those is why…

***