An early lesson

My father’s den was a small dark room with floor-to-ceiling bookshelves packed tight with crime paperbacks. I spent hours going over the spines. Hammett, Christie, McBain, Gardner, Spillane, Woolrich, Simenon, Creasey, Stout. It was the scene of my earliest education in detective fiction.

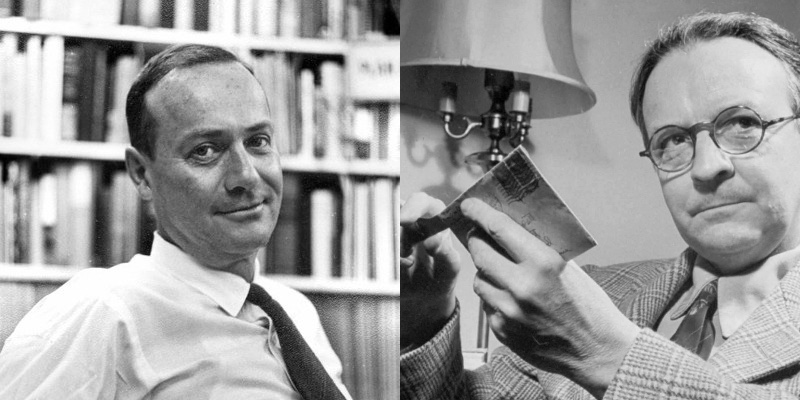

Raymond Chandler and Ross Macdonald got pride of place on his shelves. Low and easy for a child to reach. Before I knew anything about plot or theme, what drew my hand were the covers.

The Chandler novels, published by Ballantine Books, featured lush illustrations violent with color. Men loomed, faces leered. Everything hot and moist. Farewell, My Lovely with a blood-red hummingbird hovering at a white cactus flower. A cadaver-faced gangster, his gun almost an afterthought in his hand.

How could I not start reading?

Next to them, the Ross Macdonald paperbacks, published by Bantam, seemed flat and austere. Each cover bore a heavy load of type, and a minimal photograph cropped within a narrow box. While the Chandler novels attracted me, the Macdonald novels disturbed me. The Ivory Grin with its photograph of a skull and flowers. Meet Me at the Morgue with a sheet-covered body on a slab.

Reading them gave the same impression. Where Chandler served up Moose Malloy with his hulking size and clownish outfit, his mixture of menace and sadness, or Terry Lennox with his damaged face and Silver Wraith Rolls Royce, by contrast Macdonald delivered quiet prose and domestic scenes. I started reading The Underground Man and didn’t know what to make of Lew Archer feeding peanuts to the birds.

No surprise I dug into Chandler, rereading him over several summers. It took another decade before I gave Macdonald a second chance.

What I was responding to were competing theories of how a story is told. Chandler’s plots were like his covers: vivid images threaded like beads on a string. Each scene polished for maximum immediacy. Macdonald’s plots were like his covers too. Story threads that accumulate meaning slowly over time, and only through context to other threads.

This is still how I understand the shapes of detective fiction today. Chandler was stringing a necklace. Macdonald was weaving a tapestry.

The bead game

When William Faulkner and Howard Hawks collaborated on the film version of The Big Sleep, the director called Chandler to ask who killed the chauffeur in one of the key scenes. Chandler famously didn’t have an answer. What matters about this anecdote is not that Chandler didn’t know, but that he didn’t care. The point of the scene was the emotional necessity of a body in that moment, the image of the Packard resurrecting from San Francisco Bay.

Chandler crafted experiences strung along the storyline of the detective’s investigation like beads on a necklace. Each bead self-contained and polished to shine. His novels derive their authority not from logical completeness but from emotional coherence.

Think of the hothouse at the Sternwood mansion in The Big Sleep: the rotting vegetation, the sense of moral decay made physical. This scene doesn’t solve anything. It doesn’t need to. It exists to be experienced. The heat is excessive, the growth unnatural, the air barely breathable. Chandler shows a world corrupted before the mystery begins. The corruption isn’t a clue, it is a condition.

This is Chandler’s bead game at its most confident. In “The Simple Art of Murder” he self-deprecatingly described his plot method: “When in doubt, have a man with a gun burst through the door.”

What he meant is that each scene is built to be felt. The detective encounters bead after bead, not because they are logically strung, but because they are impressively strung. The success of the story lies in the mood it creates, the sense of the world it leaves behind. What matters is not whether every plot question is answered, but whether the reader has been led somewhere.

This helps explain one of the most notable facts about Chandler’s work: he wrote only seven complete novels, yet every one has been adapted for film, many more than once—The Big Sleep, Farewell, My Lovely, The Lady in the Lake, The Long Goodbye. His stories are ready-made for the screen not simply because of their dialogue or style, although Hollywood loves both, but because his scenes are already self-contained units, ready to lift, rearrange, or extend. You can clip one out, make the necklace longer or shorter, and it still holds together.

Chandler’s background makes sense of this approach. Classically educated in England, he began as a published poet, but Romanticism didn’t pay the bills. He returned to the States and became an executive in an oil company. When the Great Depression ended that path, he turned to the pulps and applied his poetic instincts to detective stories.

The result is startlingly imagistic. His novels read more like detective poems than plotted fiction. Chandler does not so much solve mysteries as assemble them. His necklace shines because every bead catches the light on its own.

Pulling the threads

Ross Macdonald built something else entirely. There is still an investigation, but the detective does not move from bead to bead, encountering scenes in the moment. Instead, he pulls a thread and unravels a tapestry of lies.

The case begins, but it is not the beginning. The real crime is buried in the past: a switched identity, an abandoned child, a family tragedy long suppressed. Yet the past has been covered up. This is the tapestry. As Lew Archer pulls on its threads, the accumulated damage from one generation to the next becomes visible.

Chandler, the poet who worked behind a desk as an oil executive, brings to mind T.S. Eliot, another poet who worked a day job at Lloyd’s Bank and wrote The Wasteland between drafting financial memos. Yet it is Macdonald who embodies the truth of Eliot’s famous dictum: the past is always present. In our beginning is our end.

This is what makes Macdonald a quiet author. His scenes accumulate meaning. A conversation may appear trivial until it is placed beside another. A casual remark about a missing daughter, a half-forgotten marriage, a name that doesn’t quite fit: details that mean nothing until, pages later, they mean everything. There are no standalone beads.

This is also why Macdonald resists adaptation. He wrote eighteen Lew Archer novels, yet only two ever made it to the screen, and those just once each. His scenes are stitched tightly together. Remove one and the pattern falls apart. The highlights of a Macdonald story are revelatory rather than physical: moments that reverberate backward, altering their own meaning. Hollywood can’t tinker.

Like a character in his novels, Macdonald’s own past shaped his present. Abandoned by his father at age four, he rose above a broken family to earn a doctorate in literature, writing a dissertation on Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s theory of organic unity. Coleridge argued that a work of art must grow as a living whole, each part interrelated and interdependent. Scenes exist to reveal how the present has been shaped, and deformed, by the past.

In The Chill, a bride’s disappearance leads Archer to a twenty-year-old murder. A seemingly trivial detail mentioned in passing lies dormant until later revelations show it as the origin of generational lies. His plots are less like investigations than genealogies, mapping violence, betrayal, and secrecy moving through families across decades.

The missing end

Chandler claimed that a good mystery is one you would read even if the last chapter was missing. An extraordinary statement for a genre built on solutions.

But it makes sense once you understand Chandler’s plots as necklaces. The pleasure isn’t in the string, it is in the beads. Each scene delivers its own satisfaction, and if the final bead is lost, the necklace may be incomplete, but the experience remains intact. The ease with which Hollywood can clip Chandler’s scenes and rearrange them is proof.

Macdonald without the last chapter would be incomprehensible. With no revelation, there are only fragments. The ending is not an add-on, it is the moment when the accumulated weight of the past becomes unsustainable. What Chandler can shrug off, Macdonald cannot. Everything leads toward the final discovery that sends vibrations backward, rewriting prior scenes.

If you stop reading The Chill ten pages from the end, you haven’t just missed the solution—you’ve misunderstood every conversation that precedes it. Scenes that once seemed incidental become catastrophic, and relationships that appeared stable are revealed as carefully sustained fictions.

This difference reflects not just two approaches to plot, but two ideas about truth and how novels end.

Chandler’s truth is experiential: his detective feels the world deeply. It affects him, no matter how much he denies it. Marlowe battles corruption and crawls home to fight another day. There is no balance at the end of his novels, only the exhaustion of survival.

Macdonald’s truth is diagnostic. It must be uncovered, pieced together, understood over time. He doesn’t want to be a poet, he wants to be a psychoanalyst. Archer’s ending arrives only when past traumas are exposed. Wrongs are revealed but never righted. The damage can’t be undone.

In a way, Macdonald is writing moral ghost stories. The present is haunted by the past, and the novel becomes a kind of exorcism. Chandler is writing moral fever dreams, hallucinatory journeys through corruption. There is no past worth redeeming.

Both detectives end alone and unsatisfied. Philip Marlowe because he lives in a broken world he can’t change. There are always more beads ready to string. And Lew Archer because he has to break the world to solve his case. Once he unravels the tapestry, all he has left is a handful of colored threads.