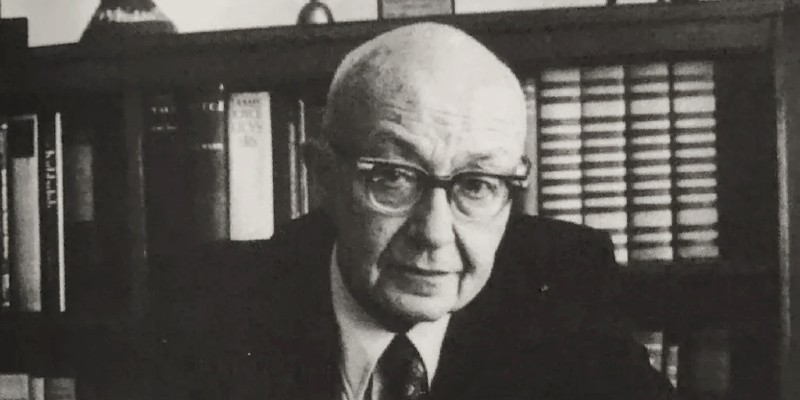

Like many poets, Charles Reznikoff (1894-1976) spent much of his life toiling in literary obscurity. He helped found the Objectivist Press in 1934, which printed William Carlos Williams and other poets, and positioned himself as a writer of “objectivist” poetry, which he described as “the objective details and the music of the verse; words pithy and plain; without the artifice of regular meters.”

Reznikoff is perhaps most notable for two epic works of poetry, “Holocaust” (1975) and “Testimony.” The latter has a lengthy, tangled history. Originally birthed as a slim prose volume in 1934, it grew into a massive tome of poetry (subsequent editions rolled out in 1965 and ’68), all of it distilled from thousands of pages of courtroom testimony that Reznickoff, who was trained as a lawyer, read as part of his job at the American Law Book Company. Academic scholars might group Reznikoff with William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, and George Oppen, but “Testimony” also brings him closely in line with the great noir writers like Dashiell Hammett and many others who also portrayed bloody deeds in stripped-down prose.

Every poem in “Testimony” is an all-American tragedy. People are shot over firewood and bad bets and bad marriages; crushed beneath trains and horses and industrial machinery; jailed, evicted, and left to die. Every line is stripped down to the starkest details. For example:

“The owner of the store told them to get away

and not to raise a row

and then turned and went on.

but, in a little while, the stranger came running after him

and Joyce and his companion were throwing stones and bottles at the

stranger—

until a stone thrown by Joyce

struck a stranger on the head

and broke his skull.”

Reznikoff left out each case’s broader context or court ruling (and changed any identifiable names and places). He took the remaining facts and used them as the scaffolding for each poem, choosing to emphasize certain actions and details over others. The result makes each crime seem universal, a Platonic ideal of mayhem. Such as:

“She turned to look at her father:

he was pulling a pistol from his pocket

and she heard her mother say, ‘Oh, George, don’t shoot!’

But he did and shot her mother

Then he went towards the back door and fired at his daughter—

she was out on the back porch looking in,

fixed to the spot.

He fired through the screen door

and the bullet struck his daughter through the left breast.”

As you might expect, given the subject matter, “Testimony” has a lot of violent action—perhaps the largest amount of violent action in any poetry collection published over the past century. It might have derived from court testimony, but it also reads a bit like the pulp magazine mayhem of the period:

“As he lay there, they kept shooting at him

and a bullet went through one of his lungs:

he knew it because the wound whistled when he moved.

He called to his friend—who had jumped first—to help him

but his friend was unconscious and did not answer.”

Compare Reznikoff’s poetry to Dashiell Hammett’s prose in “Red Harvest,” the famous noir novel in which an entire town descends into bloody chaos, from one-on-one murder to massive shootouts in broad daylight. A former Pinkerton agent, Hammett might not have engaged in all the underworld adventures he subsequently claimed, but he definitely churned out his share of reports, writing “to a certain understated standard, presenting a collection of rogues rendered matter-of-factly, with a surprisingly light touch” (in the words of Hammett biographer Nathan Ward).

The influence of constant report writing is clear in the concise way Hammett describes killing and maiming. Like so:

“A short thick-set man in brown lay on his back with dead eyes staring at the ceiling from under the visor of a gray cap. A piece of his jaw had been knocked off. His chin was tilted to show where another bullet had gone through tie and collar to make a hole in his neck.”

It’s easy to see how someone like Reznikoff could take Hammett’s prose and render it as poetry. Again, from “Red Harvest”:

“We bumped over dead Hank O’Marra’s legs and headed for home. We covered one block of the distance with safety if not comfort. After that we had neither.”

Now rendered through the filter of objectivist poetry (with hearty apologies to Reznikoff):

“We bumped over dead Hank O’Marra’s legs

and headed for home.

We covered one block of the distance with safety

if not comfort.

After that we had neither.”

Hammett wasn’t the only practitioner of a stripped-down prose style, and such a style isn’t limited to the noir and crime fiction of the 1920s and 1930s. George V. Higgins, for example, worked as a lawyer before becoming a crime novelist, and much of his work has the rhythm of court testimony. From his novel “The Friends of Eddie Coyle”:

“Scalisi came back to the table. He picked up a chair quietly and sat down. He rested his forearms on his thighs, the revolver held loosely in his right hand.”

Among poetry aficionados, Reznikoff exists at the intersection of a handful of poetry movements, including “found poetry” (which always takes its words from a pre-existing text of some sort). But it’s also worth considering him one of the first (and best) noir poets, Hammett’s lyrical cousin. He deserves more mainstream recognition.