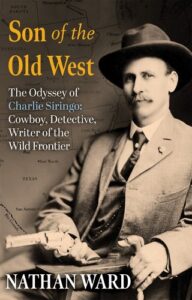

The following is an excerpt from Nathan Ward’s new book about Charlie Siringo: Son of the Old West, now available from Atlantic Monthly Press.

___________________________________

Along the snowy road from Cheyenne toward Fort Douglas, the roundup season was well finished. This was the time of year when the Round-up Number 5 saloon held on to what few paying customers strayed in. It was a low-ceilinged country bar on the Douglas road that made most of its year’s money off seasonal cowboys, and so lavished attention on winter visitors like the guest who called himself Charlie Henderson. Looking disheveled but approachable, less like a killer than a common outlaw, he wore a rounded mustache slightly darker than his ruddy face, a strapped Colt bulging a little through his shirt.

His hosts were the saloon’s lonely owners, an older couple named Howard. The husband had first been a policeman and saloon owner in Cheyenne, where he met his wife, who had worked as both a dance-hall girl and a professional fighter. As the Howards drank with him in their quiet bar, Charlie Henderson explained that he was a Texan driven north by mysterious troubles.

As he collected himself to go, the Howards coaxed him back inside for a last round, leading Charlie to return the favor and so on. He struggled to climb aboard his horse a second time, and asked about places to stay on his way to Fort Douglas, saying he would be all right if he could just “run across some Texas boys.” Howard warned him off stopping at the Keeline Ranch several miles way, as those Texans were ex-convicts who hated visitors and might happily kill him. Siringo answered that as long as they were Texans, he would take his chances. Before mounting up, he made sure to buy a bottle of Howard’s high-labeled cheap whiskey, which he slipped in his coat as a gift for the strangers. He had intended to play it a bit drunk as he rode off in search of the horse trail, but the last rounds had added to his boozy authenticity. Spurring his horse and giving a yell, he made a crashing exit through the timber toward the bridle path Howard had reluctantly described.

As his new friends watched him nervously out of their sight, he planned to fake a broken leg for his first impression on the outlaws. High in the range he was crossing, he dismounted at an inclined spot on the trail, then shoved downhill at his horse until the animal finally rolled over in a dry arroyo, leaving a dusty impression, in case his accident story was later checked. He next ripped his jean leg almost to the knee, rubbed the skin with grass and rolled up his wool drawers above the kneecap to present a scratched, swollen look, pouring on some of the Howards’ cheap whiskey as a last touch. The scar from Sam Grant’s long-ago shot added to the knee’s injured look. After tying his loose boot to his saddle, he carried on toward the Keeline Ranch, leg hanging uselessly outside the stirrup as he emerged from a stand of cottonwoods around sunset and spotted some log buildings.

A gang of men soon appeared, led by a rangy figure who turned out to be the Keeline’s foreman, Tom Hall, demanding to know “what the hell” young Henderson was doing at his ranch. When Charlie announced his leg was broken, the group carried the small stranger off his horse and into the house, where Hall inspected the knee and pronounced it merely sprained, then washed and wrapped it. A search party with lamps was dispatched to backtrail and check for signs his horse had truly rolled, as Charlie claimed, then to confirm he’d been directed to them by the saloonkeeper, Howard. Nursing his fake injury by the fireplace was the deepest any detective had penetrated the Keeline compound.

Siringo immediately recognized a “sullen, dark-complexioned man” from his boyhood days in south Texas, Jim McChesney, and worried the recognition was mutual when he asked Charlie if he was one of the scandalous “Pumphry boys” who had left town after a family killing. Siringo curtly answered, “I go by ‘Henderson’ now.” After serving their crippled guest a late supper, Hall gave him his own room, where Charlie unwrapped and stretched his leg, sleeping with his head on his “war bag” holding his belt of cartridges. His hidden Colt and bowie knife had somehow escaped notice when the men had carried him to the house. But that night, the gang discussed hanging him to scare a confession out of him, he later learned. Hall overruled the skeptics, arguing that if he was a detective it would emerge over time anyway, and they could enjoy hanging him then. After a fitful night, Charlie rewrapped his leg and hobbled to breakfast for the gang’s verdict. Hall fashioned him a wooden crutch, welcoming him for now to the desperado ranch.

Illustration by Nick Ward.

Illustration by Nick Ward.

Over the next weeks, Charlie stumped around with the gang, tying his crutch to his saddle when they rode as a group. His quarry, Bill McCoy, had left before Siringo even arrived, sent over the mountains on Tom Hall’s roan horse and now on his way to New Orleans, where he planned to board a steamer and carry Hall’s letter of introduction with him to a gang in Buenos Aires. From Jim McChesney, Charlie had learned something else about McCoy, that he was a Texas cowboy Charlie had known from the Panhandle, when he went by Bill Gatlin. Siringo’s upbringing had so far kept him alive.

The gang traveled together to a sporting house a mile outside Fort Laramie. All danced and drank and shot out windows except for Charlie, who used the excuse that his crutch kept him from dancing. He sneaked into town as the party raged and checked into a hotel long enough to write home and mail reports to tell the Denver office that Bill McCoy was in New Orleans. Then, as the soberest man in the group, Siringo inherited the job of settling the men on their horses, removing the cartridges from Jim McChesney’s sidearm, which Jim uselessly snapped at enemies on the weaving ride home.

The saloonkeeper Mr. Howard, who had reluctantly directed Siringo to the Keeline, appeared one night, heavy with the news that his wife was dying. Howard was a tolerant friend of the gang, so Hall assembled the men to ride together to his bar to keep a drinking vigil. Mrs. Howard demanded liquor to the end, dying around midnight, when they staged a wake for her in the saloon, shooting holes in the walls as the whiskey stocks drained. Later, during the ceremony to lower her into the hard ground, among the toasts and other songs, Charlie heard the mourners sing one that was possibly ominous:

Oh see the train go ’round the bend, Goodbye, my lover, goodbye;

She’s loaded down with Pinkerton men, Goodbye, my lover, goodbye.

Siringo finally tossed away his crutch before the gang made its next long ride from the ranch to Fort Laramie. He staged his recovery in order to dance with a young woman whom he could later pretend to visit when he finally disappeared for the railroad station. He again slipped away from the party long enough to send more reports.

Siringo’s original target had fled to South America, but he had learned enough from his weeks with the gang, including heart-to-hearts with Hall and McChesney, to send a posse back for them from Cheyenne. A little after sunrise, a group of riders appeared at the edge of the timber stand overlooking the log houses. When they rode up to arrest the sleeping gang, Tom Hall remarked, “That damned Henderson is at the bottom of this.” Charlie had never returned from his last visit to his girl.

Life undercover would become increasingly murky. Siringo testified against the gang to a grand jury convened in Cheyenne, but when the case fell apart before trial, he found he was strangely glad for his “friends.” Having done his job well, he had nevertheless come to enjoy these Texans whose lives echoed his own. “My friends were liberated to my great joy,” he wrote. In one sense, the manhunt had been a failure, since the real culprit, Bill McCoy, had already killed again and joined a new group of Texas outlaws on the Argentine Pampas. Tom Hall, whom Charlie would later see in Utah running a saloon under his real name, Tom Nichols, had shown a big heart in caring for a stranger’s “broken” leg and saved his life when others demanded his hanging. Charlie had returned the favor poorly.

___________________________________