The Other Half, my debut satirical crime novel, was very much lampooning a very particular sort of privileged Englishman. Boarding School, hoary titles, Oxbridge less through intellectual ability but more through breeding, emotionally stunted, wealthy, white, straight, male. I wrote it during the pandemic, shut away in my flat unable to leave the building other than to go to the supermarket or for a daily walk of an hour. The country was being run (poorly) by Boris Johnson: old Etonian, human labrador in the worst inattentive way possible, wiff-waffer in chief with his unkempt hair, untucked shirts and habit of chucking the odd bit of Latin around to make you think he’s clever and not wholly unsuitable for the highest office in the land. In this government scandals of expedited PPE contracts for connections, trips to historical monuments to test ones eyesight, and parties thrown while the rest of us stayed put, isolated in our homes stepping onto our doorsteps at 6pm every evening to clap the NHS workers tireless trying to save lives were common. Sir Rupert Beauchamp was the manifestation of this upper class boogey man. A dashing baronet with everything and yet broken. Committing horrors that no one cared to do anything about.

In short, with The Other Half I took aim at one specific, egregious trope; however, with The In Crowd—the second novel in DI Caius Beauchamp series—I went wider with my scope. A crew of rowers crash into something on an outing on the idyllic Thames. A piece of flotsam? Rubbish haphazardly chucked into the river? No, they smash into the body of a woman. She’s left in the morgue for a week. The tragic Thames has seen many poor, unfortunate souls drown themselves over their misfortunes over millennia. This woman was no different surely? The police are underfunded and will likely assumes that the woman, living in poverty nearby in a damp riddled flat, is just another suicide. This case isn’t going to be investigated beyond a cursory glance—until a government minister summons our hero DI Caius to his Mayfair club—full of dubiously acquired artwork and passable port—and insists on it, exchanging Caius’s involvement in this case with a carte blanche to investigate another cold case. In this instance, the unsolved disappearance nearly fifteen years prior of a schoolgirl from a neglectful boarding school in Cornwall that Caius has a vomit-splattered lead on.

Britain is an unequal society. Race, religion, sex, gender, sexuality—yes, people are routinely and appallingly discriminated against because of these characteristics. But, the great ‘ism’, the superhighway that all others cross is class. It is incredibly difficult to change social class. It is not a question of wealth. Wealth and class are not the same thing. You could be as rich as Croesus and still be looked down upon because of who your family are, how you spend your money, what you wear, how your house is furnished, where you holiday, your accent. Money helps, of course, but there is a set of cultural values, received pronunciation, and a whole lifetime of shared experiences like boarding school, that one’s earnings cannot surmount. As Nancy Mitford delighted in telling Britain’s sharp elbowed middle classes in the 1950s there’s a whole parallel language too.

So much of the thankfully late Tory government seemed to hinge on a very English sort of class allegiance: a chumocracy. There was a ‘VIP lane’ for those connected to the Tory party to secure PPE contracts during the pandemic. Tory Peer Michelle Mone and her husband Doug Barrowman are being investigated by the National Crime Agency over allegations of bribery and fraud in their securing of £200m in government contracts for a company called PPE Medprois. There was so much abuse of public funds that Rachel Reeves, the new Chancellor of the Exchequer, is appointing a Covid corruption tsar to retrieve a staggering estimate of £2.6bn that was lost from waste, fraud and flawed contracts during the pandemic. It feels very much that there’s one set of rules for one type of person and another set for the rest of us.

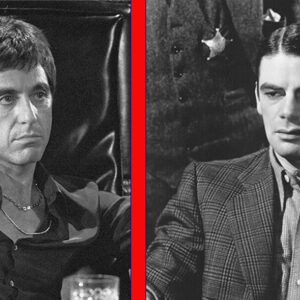

I was searching for inspiration after binning an earlier attempt at the dreaded second novel, and starting again from scratch with the deadline fast approaching. I trawled through BBC iPlayer hoping the muse would be lurking amongst last week’s soap opera episodes and sitcoms and found a documentary: House of Maxwell. Imagine a captain of industry, a publisher and later a press baron going toe-to-toe with Murdoch, buying newspaper after newspaper including the New York Daily News. He’s a decorated war hero. A Czechoslovakian by birth, he escaped the Nazis and joined the French Foreign legion as a teenager. Later on, he joined the British Army, landed on the Normandy beaches and is eventually awarded a Military Cross for storming a German machine-gun nest. He’s clever, a polyglot, with wide ranging intellectual interests. He’s a former Member of Parliament. The British elite with their old school ties and old boy networks has welcomed him with open arms. He lives in an idyllic manor house in the Oxfordshire countryside – that he leased from the local council no less – in which his family live a life of luxury that is rare amongst the majority of Britain’s aristocracy whose inherited estates all have leaky roofs and creaky sofas about to collapse under the weight of their twelve cocker spaniels. Anyone who’s vaguely anyone attends his 65th birthday party. Imagine he’s also a crook.

November 4th 1991, and Robert Maxwell’s yacht the Lady Ghislaine—named after his now infamous daughter—is off the coast of the Canary islands. He’d gone alone on a trip. His executives who know something is wrong with the company finances can’t get hold of him, and Maxwell knows that they know there’s missing millions because he’s bugged them. A member of the ship’s crew goes into his cabin to wake him at 7:15am but he’s not there. Maxwell has disappeared. His body was later found floating in the Atlantic and ruled an accidental drowning. The holes in Maxwell’s finances were discovered not long after his death. His companies were on the verge of collapse. After a host of failed ventures were covered up by shunting money from one company to another in order to fool auditors, he raided the Mirror Group’s (a collection of British newspapers) pension fund to the tune of £460m. What struck me about Robert Maxwell’s pension theft was that while Maxwell was up to no good, the great and good were getting cosy. He seemingly had managed to vault through the class ceiling because although he wasn’t ‘the right sort’, he was rich, but more importantly as the owner of newspaper he was powerful.

Power, no matter how dubiously it is obtained, talks in a sweeter and more pleasing accent than money. To my mind one of the simplest ways to make power taste bitter is to ‘take the piss’. Crime is an inherently satirical genre. It lends itself beautifully to examining what’s wrong in society. I am naive perhaps, but if I can speak a little truth and garner the odd laugh while I’m at it then I consider my job done.

***