East of Vine and south of Sunset, beyond the glittering marquees of Hollywood Boulevard, there once stood a smaller, scrappier dream factory: A cluster of musty warehouses and cramped offices, where independent filmmakers spun studio short ends into B-movie gold – as quickly and cheaply as possible.

In those days, movies were a land rush business, and independent theaters across the country were starving for product – be it tenderloin or rump steak. From the 1920s to the 1950s, “Poverty Row” cranked out hundreds of singing cowboys, bug-eyed monsters, Bela Lugosi chillers, and turgid melodramas, all made on couch-cushion budgets. Many of these movies were shot in five days, sometimes with discarded set pieces scavenged from the majors.

As you might expect, a lot of Poverty Row pictures were dreck. But every so often, something exceptional slipped through. The low budgets and lawless atmosphere granted filmmakers greater latitude to experiment. Here are five of the brightest diamonds in the Poverty Row rough, starting with the crown jewel:

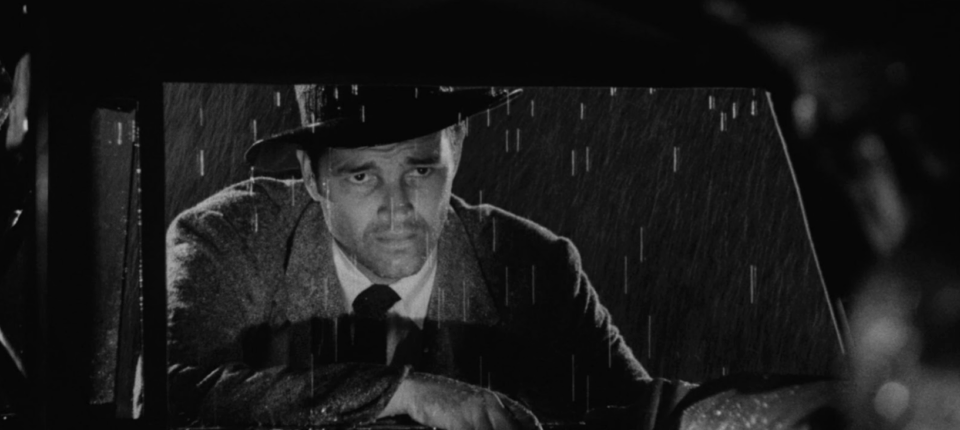

Detour (1945, Edgar G. Ulmer)

Edgar G. Ulmer, the Austrian-born director of Detour, made nearly 100 films in his career, mostly low-budget B-pictures for Poverty Row studios. But he didn’t start out in the gutter. In the 1920s, he was a set decorator at the height of German Expressionism, assisting the master himself, F.W. Murnau.

Murnau brought Ulmer to Hollywood to work on Sunrise, and in 1933, he directed his first American film – Damaged Lives, a low-budget exploitation flick about the horrors of venereal disease. A year later, he scored a smash with The Black Cat, a Universal hit starring Lugosi and Karloff. Ulmer’s star was on the rise. And then he fell for the wrong woman – the wife of the studio head’s nephew. By 1936 he was persona non grata, exiled from the majors and banished to the shadows.

Detour (1945), based on Martin Goldsmith’s novel, follows Al Roberts, a broke pianist hitchhiking across the country to chase a dame, who stumbles instead into a nightmare. Tom Neal plays Al, and Ann Savage scorches the screen as Vera, a femme fatale described in the book as “like a frozen stick of dynamite.” Watching Savage deliver the line “kiss him with a wrench” is itself worth the price of admission.

Ulmer shot the movie in six days for $20,000 – if he is to be believed. He flipped negatives, recycled sets, and cut corners wherever possible, and still managed to conjure a film whose rough edges line up perfectly with its story of doom and inevitability.

Like the films of David Lynch, Detour has a jagged, unresolved quality that lingers. Critic Andrew Britton suggests Detour is the fevered invention of an unreliable narrator. Al isn’t telling us a story – he’s clawing together a defense.

“Whichever way you turn, fate sticks out a foot to trip you,” Al grumbles. The same could be said by Ulmer himself. Banished from the majors, he never escaped Poverty Row. But Detour did. It’s in the National Film Registry now, one of the only B-movies canonized as American treasure, and pound for pound, one of the most profitable noir films ever made. How’s that for a twist of fate? You can watch Detour on Tubi.

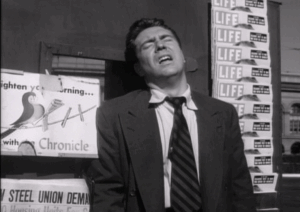

D.O.A. (1949, Rudolph Maté)

If Detour was the crown jewel of Poverty Row noirs, D.O.A. is one of Poverty Row’s flashiest baubles. It begins with a man walking into a police station to report his own murder. Frank (Edmond O’Brien) has been poisoned fatally, and he spends his last hours scrambling to learn who did it and why.

Producer Leo C. Popkin made D.O.A. for his short-lived Poverty Row outfit, Cardinal Pictures. Critics barely noticed. The New York Times dismissed it as “only a mild divertissement.” When Cardinal folded, filing errors sent D.O.A. tumbling into the public domain. For years it languished in cheap TV syndication until critic Foster Hirsch reappraised it in 1981:

“One of the film’s many ironies is that his last desperate search involves him in his life more forcefully than he has ever been before… Tracking down his killer just before he dies turns out to be the triumph of his life.”

Fun fact: D.O.A. contains one of the first-ever “stolen shots” on a real San Francisco street, taken without city permits. Watch out for the confused pedestrians as a sweaty Edmond O’Brien staggers through their midst. You can witness it on Pluto.

Blonde Ice (1948, Jack Bernhard)

Claire Cummings (Leslie Brooks) is a San Francisco gossip columnist by day and a man-eating hellion by night. She marries rich, cheats richer, and never met a sucker she couldn’t bleed dry.

Based on the 1938 novel “Once Too Often” by Elwyn Whitman Chambers, Blonde Ice was panned by critics (“It’s not a nice film,” one critic sniffed). And yes, it’s silly, aside from George Robinson’s snazzy cinematography. But Claire Cummings fascinates. Her ruthless hunger for money and status feels… contemporary. Was she the original girlboss? You can find out by watching Blonde Ice on Tubi.

Raw Deal (1948, Anthony Mann)

Trembling shadows. Fog-cloaked alleys. Raymond Burr. Raw Deal is noir distilled to its darkest essence. Directed by Anthony Mann, who would later trade shadows for sagebrush with Winchester ’73 and The Naked Spur, and shot by the legendary John Alton, the duo turned a bus-fare budget into one of the most visually striking noirs ever made.

Joe Sullivan (Dennis O’Keefe) is rotting in prison, stewing over the $50,000 he took the fall for on behalf of big bad Rick (Raymond Burr). Rick arranges Joe’s “escape,” expecting him to be shot down or shoved back into a cell for good. Instead, Joe actually makes it out, thanks to his smitten ride-or-die Pat (Claire Trevor) and Ann (Marsha Hunt), his bleeding-heart caseworker turned accomplice. Bullets and betrayals ensue.

Raw Deal was one of only a few noirs to be narrated by a woman, and Paul Sawtell’s score was one of the first to include an electronic instrument (the Theremin). You can find it on Kanopy.

Gun Crazy (1950, Joseph H. Lewis)

Originally titled Deadly Is the Female, Joseph H. Lewis’ Gun Crazy stars John Dall as Bart, a gun-obsessed drifter who falls under the spell of Annie, a carnival sharpshooter (Peggy Cummins).

Based on the short story by MacKinlay Kantor, first published in The Saturday Evening Post, the film was scripted by Kantor and “Milliard Kaufman” – a front for blacklisted scribe Dalton Trumbo. He is credited with twisting the source material into a doomed amour fou.

What Gun Crazy lacks in budget it makes up for in bravura camerawork. In one famous sequence, Lewis pulls off a 17-page bank robbery in one shot. To capture it from inside the car, the back was gutted and outfitted with greased planks and a jockey’s saddle. No one outside the actors and the bank managers were aware that a movie was being filmed. As Dall and Cummins made their escape, an actual bystander can be heard screaming after them.

Produced by Monogram, purveyors of early John Wayne oaters, the film was dismissed at first as tawdry theatrics. But its reputation grew. Eddie Muller, noir historian and president of the Film Noir Foundation, has hailed it “the most exciting, dynamic, and influential noir ever made.” You can stream it (where else) on Tubi.