The Harlem Detectives arrived like a thunderbolt.

Like a meteor screaming across the sky.

I had seen detectives before, but nothing compared to this.

Or so I felt when I was introduced to Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones.

They make their appearance at the start of chapter 8 of A Rage in Harlem, the 1957 novel that started Chester Himes’ Harlem Cycle, conducting their unique brand of “crowd control” at the legendary Savoy Ballroom:

“Grave Digger stood on the right side of the front end of the line, at the entrance to the Savoy. Coffin Ed stood on the left side of the line, at the rear end. Grave Digger had his pistol aimed south, in a straight line down the sidewalk. On the other side, Coffin Ed had his pistol aimed north, in a straight line. There was space enough between the two imaginary lines for two persons to stand side by side. Whenever anyone moved out of line, Grave Digger would shout, “Straighten up!” and Coffin Ed would echo, “Count off!” If the offender didn’t straighten up the line immediately, one of the detectives would shoot into the air. The couples in the queue would close together as though pressed between two concrete walls. Folks in Harlem believed that Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson would shoot a man stone dead for not standing straight in a line.”

In 1957, in Chester Himes’ New York City, Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones are the only two black detectives in the NYPD. Their beat is Harlem. From 110th Street at the northern end of Central Park uptown to 155th Street. From the Hudson River crosstown to the East River. Coffin Ed and Grave Digger are “just possibly the two toughest men alive,” according to Stephen F. Milliken’s critical appraisal of the Harlem Cycle. In his finely tuned biography of Himes, novelist James Sallis describes the two detectives as “larger-than-life” figures who possess “something of the power and authority of myth.”

I consider Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson to be the hardest of all the hard boiled heroes. They would crack Mike Hammer’s skull like a walnut without blinking an eye. If Freddy Otash visited Harlem, they would have used him up like a box of Kleenex.

Here is how Himes’ describes them:

Grave Digger and Coffin Ed weren’t crooked detectives, but they were tough. They had to be tough to work in Harlem. Colored folks didn’t respect colored cops. But they respected big shiny pistols and sudden death. It was said in Harlem that Coffin Ed’s pistol would kill a rock and that Grave Digger’s would bury it. They took their tribute, like all real cops, from the established underworld catering to the essential needs of the people—gamekeepers, madams, street-walkers, numbers writers, numbers bankers. But they were rough on purse snatchers, muggers, burglars, con men, and all strangers working any racket. And they didn’t like rough stuff from anybody else but themselves.

“Keep it cool,” they warned. “Don’t make graves.”

I was introduced to Chester Himes and The Harlem Detectives by Charlie Donelan, a Central Massachusetts impresario and perennial PHD candidate at Clark University in Worcester. This was sometime in the late 1970s, around the time that Jimmy Carter was engaged in mortal combat with a fierce swamp rabbit (Sylvilagus Aquaticus) in the backwoods of Georgia. Donelan had his own connection to the Peach State. He claimed to have grown up in Waycross, Georgia where he drank rum and Dr. Pepper with Gram Parsons. He lived in a shack above the Clark campus, on one of the Seven Hills of Worcester, with the Allman Brothers Band on constant rotation, blasting from a massive pair of JBL speakers. Charlie was allegedly working on his dissertation on James Fenimore Cooper, but most nights he was holding court at the pool tables in the back of Moynihan’s Pub on Main Street.

I don’t know if Donelan ever finished his dissertation – I think he got hung up somewhere between Chingachgook and Natty Bumpo. But I do know that when the good Professor handed me his worn copy of A Rage in Harlem one night before last call at Moynihan’s I considered it a mandatory reading assignment.

In the opening chapters of A Rage in Harlem, Himes introduces his cast of Harlem eccentrics. “Stack of Dollars,” who runs the biggest standing craps game in Harlem. Undertaker “H. Exodus Clay,” the owner of Harlem’s busiest funeral parlor on Lenox Avenue who thanked his future clients every year at the Annual Undertaker’s Ball. “Sister Gabriel,” a Sister of Mercy who frequented both the craps game and the funeral parlor. For a price, Sister Gabriel would pray for your soul or bless your dice. For another price, Sister Gabriel was a stool pigeon for Grave Digger and Coffin Ed and their eyes and ears on the streets of Harlem.

After making their unforgettable appearance at the start of Chapter 8, Coffin Ed and Grave Digger play supporting roles for much of the novel. The main action revolves around stolen money, missing gold, and swift, merciless death. But, by the end of the novel Grave Digger and his “blind rage” take center stage and animate the plot. \Grave Digger becomes a one-man police force to avenge his partner Coffin Ed, who is lying in a hospital bed, fighting to survive the mortal damage caused to his face and his eyes by the acid thrown at him by a crew of hard-boiled hustlers.

Before Grave Digger heads out alone into the Harlem night to face down the crew, he tells the white Lieutenant in command of the Harlem Precinct and all of the other white police officers in the station house that he won’t need any backup:

The lieutenant frowned. It was irregular, and he didn’t like any irregularities on his shift. But hoodlums had thrown acid in a cop’s eyes. And this was the cop’s partner.

“Take somebody with you,” he said. “Take O’Malley.”

“I don’t want anybody with me,” Grave Digger said. “I got Ed’s pistol with me, and that’s enough.”

The economy and precision of Himes’ writing are diamond sharp.

Everyone in that Precinct House and everyone in Harlem who had ever “heard the chimes at midnight” – all the hustlers and the pimps, all the brothel madams and the bookies – knew the score.

They all knew that Grave Digger would be coming for the men who put Coffin Ed in the hospital.

I knew it too.

When I finished A Rage in Harlem I was hooked. I spent the better part of three years tracking down the rest of the Harlem Cycle. But no booksellers near me carried Chester Himes books. There was no market in Central Massachusetts for Himes, a Black expatriate with shadowy ties to the CPUSA, an ex-convict forced into exile from his home. I would come across a novel in the Harlem Cycle here and there over the years – in Cambridge, in New Haven, in Amherst – any town with a decent bookstore and a yen for civil rights. I read them all – Cotton Comes to Harlem, Blind Man With a Pistol, The Crazy Kill – eventually reading my way through the whole series just about the time Ronald Reagan was taking office. Then the Himes’ books practically vanished from the stacks, amidst rumors that Himes was on Caspar Weinberger’s secret “enemies list” and that the big booksellers best not traffic in the works of alleged “enemies of the state.”

I don’t know if there is any truth to those rumors.

But I do know that enemies are in the eye of the beholder and that Himes’s books hold a place of honor in my library. On the top shelf. So, in 2006, when Cap Weinberger finally shuffled off his mortal coil, I commemorated the occasion by screening a Chester Himes double feature: 1991’s A Rage in Harlem, an entertaining film which I don’t think has aged especially well, and 1970’s Cotton Comes to Harlem, a magical film which has aged like a fine claret.

With Cap Weinberger dead and gone, few people think about Chester Himes these days, and fewer still read his crime novels. But maybe the worm has turned for Himes. And maybe Chester Himes and The Harlem Detectives are finally going to get a meaningful measure of the acclaim they deserve.

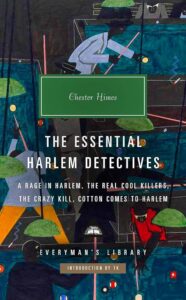

If so, then we have to thank the Everyman Library’s 2024 publication of The Essential Harlem Detectives. The collection selects – curates really – four of the eight volumes of Himes’ Harlem Cycle: A Rage in Harlem (1957), The Real Cool Killers (1959), The Crazy Kill (1959), and Cotton Comes to Harlem (1965).

It is a beautiful book.

The edition meets the highest production standards, with acid-free paper, full-cloth cases with two-color foil stamping, decorative endpapers, silk ribbon markers, European-style half-round spines, and a full-color illustrated jacket. This edition also includes an introduction, a select bibliography, and a detailed chronology of the Chester Himes life and times.

The introduction by crime fiction superstar S.A. Cosby is a heartfelt fan letter to Chester Himes and The Harlem Detectives.

Crosby says this:

“Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson are not private eyes. They are police detectives and carry with them all the psychological and sociological caveats that come with that occupation in the Black community. And yet Himes is able to garner sympathy and adulation for these two men who, within the world of Himes’s Harlem, try their best to mete out justice equally under an inherently unjust system. They use abhorrent techniques to get information from abhorrent people. They never make the mistake of thinking they are the good guys. To quote another fictional policeman, Rust Cohle, they are “the bad men that keep other bad men from the door.”

And this:

“If Chandler is considered the poet of crime fiction and Hammett its great journalist, then Himes is the songwriter of the downtrodden. His stories sing with a fire and light that comes from a simmering sense of loss. A loss of respect, of humanity, of honor.”

I could not agree with S.A. Cosby more.

The sheer exuberance of the four novels in the Essential Harlem Detectives is intoxicating. Each of the novels is essential to The Harlem Detectives arc, from their “origin story” in A Rage in Harlem through Cotton Comes to Harlem where they confront the insidious perfidy of Reverend Deke and his breathtaking affinity scams, and make more work for undertaker H. Exodus Clay.

The novels are chock full of predators, hustlers, scam artists, thieves and felons. They are all on the make, all on the lookout for the squares and the straights, for the “marks” that they can take.

In the rollicking world created by Chester Himes, Coffin Ed and Grave Digger are the only real law north of 110th Street. That law is swift and sometimes brutal and it’s not always fair. But every night Coffin Ed and Grave Digger go out into the mean streets of Chester Himes’ brilliant imagination. And every morning when the sun rises over the East River the only thing that stands between the straight and crooked, between the predator and the prey, are the shadows cast by The Harlem Detectives.

Welcome back Grave Digger Jones and Coffin Ed Johnson.

Welcome home Chester Himes.

***