“It had occurred to him a long time ago that cops working homicide had a more intimate relationship with a victim than anyone did when the victim was alive. They found out spots, lesions, scars and other indices of health and illness that even physicians might not know…

And with a little probing into the way the victim lived their life, you might find out secrets that were spoken only in the confessional, or maybe to a shrink, and sometimes not even there.”

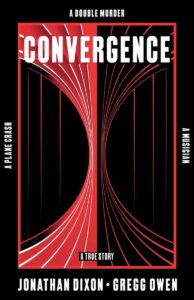

In Gregg Owen and Jonathan Dixon’s new true crime book, Convergence, readers are drawn into a fast-paced, compelling tale of a brutal double murder in late-70’s Chicago and a fairly clear-cut case that was almost closed – but thanks to former musician-turned-prosecutor Gregg Owen and his colleagues, justice is pursued, despite all the odds.

I was privileged to ask the authors of Convergence a few questions about the writing of the book.

When reading Convergence I was immediately pulled in by its strong sense of time and place: Chicago in the late 1970’s. In theory, a similar double murder could’ve taken place in other cities or eras. In Convergence, however, the reader is fully immersed in the Chicago setting. Whether it’s subtleties of dialogue such as slang and regionalisms, or vivid descriptions of various neighborhoods and meetup spots, the atmosphere drew me in completely and is a compelling aspect of the crime’s setup and consequences. Then there’s all the literary elements that factor into portraying the end of a decade, whether a political shift or an element of pop culture (especially on the musical front, given Gregg’s background). In working on Convergence, what was most helpful to you throughout your writing process in terms of being able to set this vivid environment up for your audience?

Jonathan Dixon (J.D.): I’ve lived most of my life in New York, so I understand the city mindset. The details may change from place to place, but I think there’s a definite common city experience.

That time period fascinates me—the latter-day Vietnam, post-counterculture era in America, when things got a little dark. I really steeped myself in books like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Dog Soldiers, All the President’s Men. Music like Exile on Main Street or Blood on the Tracks, a lot of disco. It was a shut-in’s version of method acting.

And I consumed a lot of Chicago media from that era—about politics, business, culture, human interest stories. Nothing specific—just in general. I wanted to get to a point where it felt like these were my memories.

When I was visiting, Gregg took me around to places that were really important in the book, and then if I could figure out how to get back to them, I’d go and just observe and wander around. The first time I did that it was winter and I got lost. I couldn’t figure the subway out, and I was too embarrassed to call Gregg and ask for help. But I can report that Chicago gets really cold.

When delving into the case, what struck you both the most – Gregg, as someone actively involved in the investigation as it was happening and Jonathan, in learning about it after the fact – in terms of the Illinois justice system during that particular era, and how the case was handled? Did you feel like the initial verdict would’ve gone similarly today?

Gregg Owen (G.O): The whole system was different back then — rough, street-level. Trials got heated…we didn’t have DNA, body cams, fancy forensics, jury consultants, or CCTV. What we did have were a lot of good investigators who trusted their gut, and we had to rely on our own skills — reading people one-on-one, not looking at screens or data. You learned to read a room fast — who’s lying, who’s scared, who’s hiding something.

In this case, we had two young people stabbed to death, one terrified eyewitness, and a defendant with money, power, the best defense team we’d ever gone up against, and all the right connections. What stuck with me was how close it came to getting tossed — not because we didn’t know who did it, but because it was easier for some folks to look the other way.

If this trial happened today, sure, it’d look different. There’d be cameras, lawyers trying to make a show out of it, and every move would get second-guessed online. But the truth? The facts wouldn’t change. The guy still did what he did. The difference is, back then we had to fight harder — with fewer tools — to make sure justice actually happened.

From a writing perspective, were there any specific strategies the two of you used to build narrative suspense throughout Convergence? I think one of the book’s strengths is that although it’s nonfiction, it does often read like a fictional thriller (which I mean as a high compliment! And of course, truth can be stranger than fiction…)

And along with that question, were you able to do some interviews years after the case with some of the people involved, such as Gio’s father and Cedric? Did they have insights much later after the case was closed that they were able to mull over and analyze afterwards in terms of things like evidence and being a witness?

J.D. The suspense came from instinct. My thinking happens in pictures, so I guess my mind is like a personal AI—it scrapes all the movies and shows I’ve fed into it for visuals, and so there’s inevitably a sense of scenes in there. And I’ve watched a lot of crime stuff over the years. Words very mysteriously emerge after that, and the visuals are like a magnet attracting tiny splinters of metal. It takes me a long time to write because I have to keep attracting and discarding splinters until it feels right, but I’m usually happy with the results.

As for the way we narrated it… here’s a confession: when I read biographies, I tend to skim over people’s early years because I want to get to the fun stuff. Novels usually start with the fun stuff. By narrating Convergence like a novel, I felt like we could start there, too.

Except for Gregg, most of the people involved are gone. I did get a chance to speak with Ted O’Connor, and I drew heavily on what he told me, but he passed before the book was published. I used what Gregg told me about people, and I could discern the way they may have thought from reading court transcripts.

After they read it, some of Mike Goggin’s (Gregg’s law colleague) family told Gregg we’d managed to capture some of the essence of Mike’s character. Gregg reported that back to me and I can’t tell you how gratifying that was.

(My personal recommendation: don’t try to read Convergence if you need to urgently go to sleep. It’s a page-turner.)