Chris Offutt published his first book when I was young and in grad school. Kentucky Straight (Knopf Doubleday, 1992) hit hard amongst us English scholars at the University of Kentucky, and we discussed it ad infinitum way back when. Some of us felt it was absolutely fantastic, maybe the finest writing to emerge from Kentucky, accurate to the mountain region where the stories are set. Others took issue, arguing that the stories seemed exploitative in places, that the portrayals devolved into stereotypes. What everyone seemed to agree on, though, was that the writing evoked a mood that got under one’s skin. The style was possessed of an artful eeriness, and there existed a constant tension that commanded a reader’s attention. We also talked a lot about Offutt’s creation of place, something unlike what we had seen in other Appalachian writers. There’s an authenticity there, we agreed, a fact confirmed by many students who had in fact been raised in the hills. (“That old lady reminds me of my mamaw . . . That guy is exactly like my uncle.”)

Another thing we all agreed on was this: Offutt’s characters are not limited to people. The hills themselves, and all of their flora and fauna, figure crucially in the story collection. Indeed, the characters–and the narrative tension generally—cannot be separated from the environs that shape them. And there was often something mystical, too, in this respect, something raw and dangerous, a courageous art formed not solely by the expression of mountain beauty, but one which juxtaposed the natural world and the (often brutal) human one. One story in particular, “Aunt Granny Lith,” fused the two worlds in such a spectacular manner that we simply couldn’t stop talking about it. (“Is it real? Is it fantastical? Are we supposed to believe this?”)

Truth be told, I haven’t stopped thinking about Kentucky Straight. And occasionally, I’ll still hash it out with an old grad school buddy over a few beers.

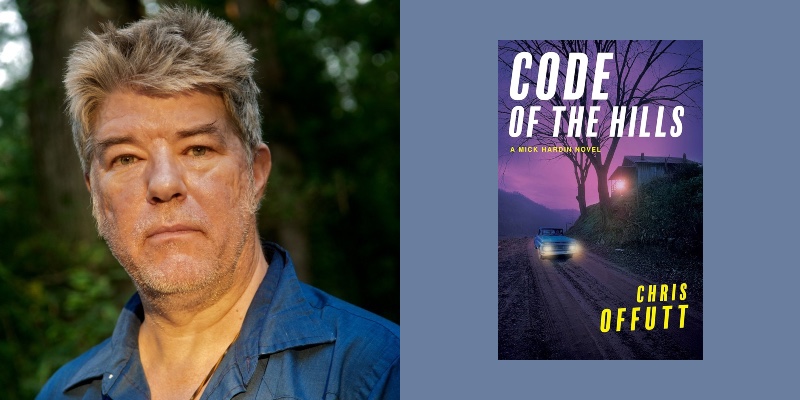

Offutt went on to write another collection of stories, two novels, and three memoirs—all incredible efforts. More recently, he’s turned out three books in a series featuring U.S Army C.I.D. cop, Mick Hardin–The Killing Hills, Shifty’s Boys, and Code of the Hills, all with Grove Press. Mick hails from the hills of eastern Kentucky, where his sister is the sheriff, and where his wife still lives, though the relationship is rocky. In between deployments overseas, Mick gets roped into solving cases back in the hollers, sometimes as a hired P.I. and sometimes as a deputized officer. The books are page turners, full of colorful characters, fast-paced action, and again, attuned to that element of place, the natural environment that lives both outside and inside so many of the characters. Mick, too, is a fantastic heavy, a quiet guy who can see all the angles, and who can handle himself amongst the toughest of mountain rogues.

I talked to Chris about the series, and the next installment, the forthcoming The Reluctant Sheriff.

Chris, in the Mick Hardin series, the natural world figures importantly. Even in really tense scenes, ones that signal impending violence, characters will actually discuss the flora or fauna surrounding them, even though they might believe someone is about to kill them. Mick especially is aware of the rhythms of nature. Can you talk about the place of the natural world in these scenes, or across the series in general?

The hills of eastern Kentucky are filled with birds, wildflowers, small game, and a blend of deciduous and evergreen trees. There’s more examples of flora and fauna than anywhere in North America. More animals than people live in the hills. I grew up there and learned to love what the woods offered, especially birds. Mick and the characters reflect my love of nature.

I believe that humans are strongly affected by the surrounding terrain. We are especially imprinted with the natural world of our childhoods. In the hills, nature is a constant force—beautiful and relentless. At times brutal. The sounds of bird and wind in the leaves is a constant backdrop to the life I experienced as a child and as an adult.

When I write, it’s a way to return to the environment I love.

Throughout the series, people observe certain mountain “codes” for behavior, even when doing so might slow an investigation or compromise an agenda. This is a unique, compelling element to the narratives. What’s so important about mountain codes, mountain modes of action?

The hills of eastern Kentucky are one of the most isolated parts of the USA. People have lived there a long time, which led to a retention of older ways of being in the culture. It’s not heavily populated and has never had a political voice. This has led to strong self-reliance and a deep mistrust of authority. There were also fewer officers of the law in the hills than elsewhere. The combination created a way of thinking that in many instances is not about legal or illegal, but about concerns itself with what is right.

There is not an actual code, written or unwritten. It’s a term I invented to account for the cultural willingness for people to settle problems on their own. I don’t advocate vigilante justice. But it also seems clear that we don’t have a “justice system” in America, we have a “legal system.” And that legal system always favors people with money.

Mick’s sister, Sheriff Linda Hardin, plays an important role in all three novels. Sometimes the siblings are at odds—both professionally and philosophically—but at other times, they work together well. Was there much thought about this before you began writing? In other words, how did you figure that a sibling element would aid you in creating the narrative?

The most important social factor in the hills is family loyalty. This is true elsewhere, of course, but Appalachia doesn’t have the other institutions that inspire loyalty such as big companies, sports teams, or old universities. I wanted to emphasize family loyalty in the books. Although Linda and Mick are very different, with different childhoods, they are still devoted to each other as siblings.

Standard crime novels usually have a love interest for the protagonist. It’s a trope, but a valuable one that can show a softer side of the tough protagonist. The drawback is that the dynamic has only two outcomes—they stay together or they split up. With male and female siblings, they stand by each other no matter what. They may go a decade in angry silence but they can also end their hostility when they need to band together. This struck me as a far more interesting relationship to explore than that of standard romantic love.

At some point in the novels, the narrator digresses to tell a tale of some event transpired long ago. For example, there are the Branham sisters in The Killing Hills, mountain beauties from yesteryear who enjoyed the attention of handsome suitors before hard times befell them. There are other such tales about days long ago, often about loss, and even more recent histories figure as narrative digressions. What role does the past play in these novels?

As Faulkner said: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” He was speaking of Mississippi but the same can be said of eastern Kentucky. In a way, the past is not that far away. Life in the hills continued the same way for over two hundred years. All of the available land was pretty much settled by the end of the 1700s. The primary settlers were Scots-Irish, who were outsiders in both Ireland and Scotland.

The westward expansion went north and south of the Appalachian region due to the rough terrain. There were no big rivers for the riverboat trade. There was no flat land for big factories. The land was not suitable for massive farming or ranching. Periodic out-migration of young people left behind mostly older folks who helped maintain the past ways of living and thinking.

Anyhow, all this is part of why Mick ponders the past. He was raised by his grandfather deep in the woods, which also influences his way of thinking. To use your term, these “narrative digressions” are also about me and my own pondering of the past. It’s possible that I think about the past too much!

Several reviewers have noted the “accurate dialogue” in the books. What’s important about this? As someone raised in Appalachia, does the dialogue come easy to you?

I’m glad people think the dialogue is accurate. In my work the dialogue is an attempt to render a dialect and a way of thought. Writing dialogue is always difficult. It’s a balancing act, or an illusion of smoke and mirrors. Nobody actually talks the way they do in books and movies. When we talk to each other, we want to communicate. We imply and inflect. We trail off phrases, and pause a lot. We give ourselves time to think by saying “you know,” or “umm…” or “know what I mean?” But readers don’t actually want to read that!

What I do is write very long dialogue scenes, then cut them way back. Try to distill them to the essence of what’s being said. The main way I try to depict the accent and dialect is through syntax.

Who are some of the authors whom you enjoy reading?

Gosh, there are so many. I read two books a week. That seems like a lot until you do the math and it’s only about 100 books per year. I have many favorites: Flannery O’Connor, Joan Didion, James Alan McPherson, Graham Greene, Jean Rhys, Pete Dexter. I could go on and on. Nathaniel Hawthorne. Henry James. James Welch. John le Carré. Edith Wharton. Different writers had a strong influence at different times in my life.

The first writer I loved from the hills was James Still. Periodically, I re-read his novel River of Earth. Such a masterpiece!

Can you tell us something about The Reluctant Sheriff? Will this be the last in the series? And if so, what’s next for you?

It might be the last one. But then again, I’ve started a new one! The Reluctant Sheriff picks up shortly after Code of the Hills ends. It’s hard to talk about the new one because to do so will give away information about the entire series. The biggest shift is that part of the book is set in Corsica, an island in the Mediterranean, where a person from Kentucky is hiding out. And, of course, someone becomes a sheriff with reluctance