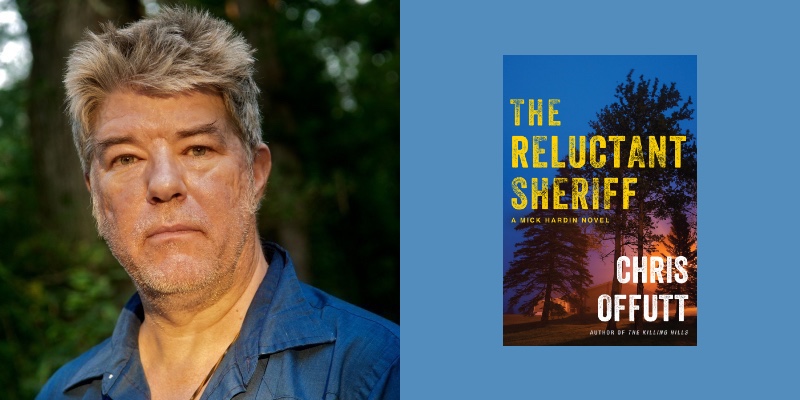

Chris Offutt has long been a “writer’s writer” acclaimed for his short story collections, memoir and novels. And though he spent his earlier career raising children and working occasionally in Hollywood, in recent years he’s been busier and more prolific than ever. Offutt’s new novel The Reluctant Sheriff is his fourth novel featuring Mick Hardin, and his fifth novel to be released in the past decade.

What’s been so striking as a longtime reader is how these new books, which Offutt admitted were written faster than he’s worked in the past, feel so much like his older work. He’s managed to change genres and craft an ongoing series, but how he works, the feel and approach to storytelling that has marked his best work, has remained. His new book, the fourth in the series also raises questions about the fact that this isn’t a trilogy or a project with a definitive ending that Offutt is working towards. While he made it clear that he never intended to write a sequel to the first Mick Hardin novel, let alone a series, Offutt was very clear and thoughtful about how he works, and how that has changed, and the joy he’s found in writing these books.

The idea for Mick Hardin, whether the character, or the story, or however you work, where did that begin? Do you remember?

No, I mean, I don’t know where. Part of it was a realization when I was a kid that the sheriff was the premier law enforcement officer in the county. There was very limited state police. The town had their own smaller police force. I knew even then that the sheriff was an elected official. So, if you have a top law enforcement who’s elected, it’s a recipe for all manner of corruption. We’ve seen that in other places. So that always interested me. I just thought about what would it be like if a county had its first female sheriff? She probably would not win elections, so she would have to be deputy who then got promoted. And in the hills – and I think I’ve talked about this before – it’s an old culture of personal retribution. Families take care of themselves. Partly because of isolation. Partly because of the lack of ready law enforcement. Partly just the historical tradition that goes back two hundred years in the hills, and further back, to the Scottish Highlands. Nobody liked the Scots-Irish. The Scottish didn’t like them. The Irish didn’t like them. They were among the first to get the heck out of Europe and come to the New World. The pilgrims took one look at them and said, you all can’t stay up here with us, man. Go down to those hills.

That means that if there was a shooting, as we called it, in the hills, most people knew who did it. And most people knew why. But people would not talk to the sheriff. Even if the sheriff knew or the deputy knew, there was just this view of, we’re going to lay back and give the families a chance to deal with things. My idea with that first book was, what would it be like if there’s the victim of a homicide, nobody knows who did it or why, and the victim was a beloved human. Everybody knew her. Everybody liked her. She didn’t have trouble with anybody. That would be a big problem, and then have a female sheriff. I thought, if she’s over her head that badly, and the patriarchy in town want her to fail, and she’s never investigated a homicide, particularly one like this, I thought, let her brother help her out. That was the start of it. I added a deputy, added another deputy. There’s a county coroner, and a few other characters. I just enjoyed spending time with them.

Writing a series is a little different, but all the books feel like your earlier work. It doesn’t feel like you’ve changed your style or approach to write them.

I never intended to write a series. COVID hit and I had a two-book contract. The first one was Country Dark, and the contract just said a Kentucky Noir. I was at a loss of what to do, so I thought, I’ll try writing something that’s a little more overt of a crime novel. In my opinion, most of what I’d written had used elements of crime. I’d written about sheriffs and criminals and scofflaws and outlaws. I thought, I’ve got time, I can’t go anywhere, I’ll just try to write one. I’ve read a lot, of course, and the solving of the crime is either paramount, or sometimes the writers will set up false trails and try to manipulate the reader into thinking it’s this person when it’s really that person. I never cared for those kinds of books. I just felt like the writer was trying to trick me. I’d rather read about a world in which it was happening. That’s what I tried to do. Just show the world of the hills of Eastern Kentucky in a way that I feel has not been portrayed adequately in any media. There’s exceptions, of course, but for the most part, there was not a sustained portrayal of not just the culture, but the way that people interact with each other. How they think – which is how I think. Also the personal relationship that everybody has in the hills with nature. Because it’s pervasive. You’re surrounded by woods, and the woods are filled with flora and fauna, and that creates a situation where the people who live there have a closer relationship to nature than most other places.

So I finished that book. It was still quarantine. I missed the characters. I’d spent more time with them than real people. I thought, I’ll write another one. Then I finished that one. I wrote these books faster than normal simply because I had all this time. Usually a book takes three years minimum for me, sometimes longer. I finished that one, and we’re still in quarantine, so I started the third. It wasn’t intentional to write a series. I’d never thought that I would. I guess I was afraid of two things. Either A, I would get bored of it, or B, do what I see some writers have done and just be repetitious. It’s easy to do that.

Previously you haven’t written crime novels, per se, but you’ve written about crime and criminals.

I like to think that I write about people who have a flexible relationship with the law. Which I do. At one point, I had to explain to my sons the difference between an outlaw and a scofflaw. They realized, oh, daddy is a scofflaw, but not an outlaw. It’s that nature of the relationship with law. In the hills there’s not much law enforcement, and there’s not much crime. You have a lot of social problems there from lack of jobs, education, medical care. The formal rules of law that regulate society aren’t as applicable as they are in other places. I think you see that in other areas in the country. Not just rural, but cities too.

As far as writing a series, in each book are you thinking, I need to mention all these details and recap what happened, and explain events?

I only have to explain them if they come up in the narrative. I started looking at series to figure out how other writers had done just that. There would often be a section where there’d be as brief a possible sort of catch up on any pertinent information that the reader might need for what was going on. That was actually difficult to do, because, you know, there’s a tendency to just put in way too much. But if you don’t put in enough, it can be equally confusing. Everything I write is set more or less than the same square four or six miles. That started with the first book in 1992, Kentucky Straight. It’s the same world. It’s not so much a repetition, it’s just that things change very slowly. There’s a different way of positioning people and places in time and space. I was concerned about it because it’s a rural environment that means they have to drive places. So there’s always sections where there’s a character driving from point A to point B, and it’s backcountry roads. How do I not have somebody driving in a truck all day? So I often have stuff happen that was unforeseen and unplanned in the narrative. Because I don’t want to read, thirty minutes later he arrives at – because you can just do that so often until it becomes an obvious sort of trick. I think that the travel is an opportunity for the character to think, to observe, and for me as a writer to see what he’s observing and the beauty of the land.

I kept thinking about how the way Mick introduces himself is a way of both capturing something about how he and others think and speak – and it’s a great way to provide information to the reader.

Well, I appreciate that. That means that whatever I was trying to do was probably working. But nothing was real calculated or planned out or thought. I’m in a situation where I try to occupy the moment as much as possible when I write. I write relatively slowly. Like if it’s half a page a day, a page a day, two pages, sometimes. Maybe three if they start talking a lot. Dialogue passages go fast. But it’s mostly unplanned. I don’t think ahead. I don’t plan ahead. I don’t plot. I don’t make an outline. That keeps it fresh. And maybe it keeps each book being distinctly different, hopefully, from each other.

Have you always worked that way, never outlining?

Always. Ever since when I started writing when I was a kid. When I started writing more seriously in my early twenties, I just wrote that way. I tried it a couple of times and after I worked out the outline, I had no interest in it. I was like, okay, I did the fun part. Now I’m just filling in the blanks on this template that I’ve made. I just never wrote the book. I did that twice and I thought, okay, I’m never going to do that again. [laughs] If I can keep myself engaged and interested and entertained on the page in the moment, my belief is that if I do that for myself, it has the potential to translate to generating interest on the part of a reader. That’s about as much as I think about in terms of “a reader.” I just want to try to write the kind of books that I would like to read. Or that I wish had been written and that I could have read.

Are you writing faster now than you used to? I ask because you’ve been more prolific in the past decade than previously.

I was a father and raising two sons. That slowed down the writing, because the kids were more important. And they still are, but now they’re out of the house, and they’re on their own. I got myself finally at age sixty, relatively stable, economically. It took that long to be able to not be terrified month to month. I think that contributes to what you call the speed of writing. The other thing is for maybe the first twenty years, I would write really fast, and have sloppy drafts. I would revise them many, many, many times, I mean, fifteen times, twenty-five times, for a single short story. Nowadays the initial draft is a little better than it was in those days, so the manuscript does not require as much focused revision. I revise less, is what I’m trying to say. It’s not that I’m writing faster, it’s just that I’ve learned how to write better. [laughs]

The Reluctant Sheriff ends in a place where it feels like this could be the last one.

Well, here’s the thing, Alex, is it was never intended to be a series. There was one book and it ends. It was not, here’s a cliffhanger for the next book. I hate when books do that. I think it’s copying bad TV. Then the second book has an ending. Both times he returns to his job in the army as an investigator. And with the third one, he was back home, and he just goes up in the woods and listens to the birds. Each ending of each of those books was sort of designed to be a finale in case I didn’t write anymore. So I’m glad that you think this one could be a real ending, but I’ve got to say, I got 140 pages of another one. I had a French publisher, say, Chris, if you get tired of writing these, just kill Mick. But you know, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle tried that, if you’re familiar with the Sherlock Holmes stories. And by golly, a few years go by and his publisher convinced him to resurrect Holmes, so that might not even work. [laughs]

Is that just how you’re working? You craft an ending, and if a little later you miss the characters and think up an idea, you write that.

I guess I have been more prolific because I’ve written other things. I have a new collection of short stories that I would love to get in print, but it’s hard to get a third book of stories in print these days. I have two other novels. One I finished last year. I tried to do these other things, and I would just kind of come back to these guys, because I love them. Ultimately, I love Mick, I love his sister Linda, I love the deputy Johnny Boy, I love the new deputy Ray Ray, I love the new dispatcher in the office, I love Marquis. I love the world. I just return to them from that standpoint. To interact with people that I deeply love, in an imaginary world that I miss every day.

You seem to be having fun with these books.

I am having fun with them. Maybe it’s age, but when I first started, I just thought, it’s literature, you’ve gotta be serious. It’s got to be dead serious in every way. I think these books are serious, but I’m able to loosen up a little bit. The biggest change on a personal level with these books, and what preceded them, for me, these books are written more closely to how I actually think. The earlier books were less about Chris Offutt and more about trying to make something that would be a very successful and strong piece of work. I don’t think I’ve given up that, but I’ve finally been able to let my truest self loose on the page. I don’t know why. I really don’t. So that’s why I think maybe it’s just age. I finally matured. [laughs]