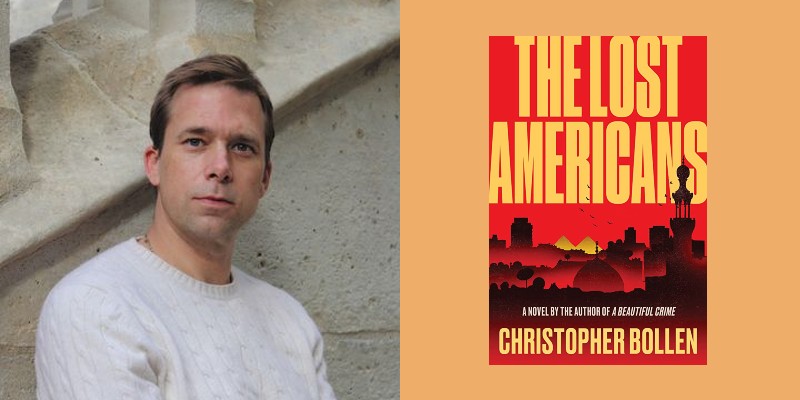

In the opening chapter of Christopher Bollen’s immersive, intricately constructed new novel, aptly titled The Lost Americans, a “weapons tech” named Eric falls to his death from his hotel balcony in the pulsating city of Cairo. Did he jump or was he pushed?

The scene shifts to his grieving sister, Cate, back in The Berkshires of Western Mass. Struggling to find meaning in her brother’s death, she bristles at Polestar’s explanation that Eric either committed suicide or had a drunken accident. “Cate would accept an accident. In the worst case, she even take murder.”

As a villainous presence, Polestar makes for an ideal embodiment of evil, and Eric and Cate had clashed over his job, Cate wondering how he could work for such a sleazy corporation who earn handsome profits as merchants of death and destruction. With his mysterious death, Cate resolves to ignore the oily, subtle warnings, false sympathy and insinuations of two suits for the company who offer a huge payoff to the family, designed to shut down any further investigation into Eric’s demise. “We want you to feel you can depend on us,” says one of the suits. “I don’t want to consider the alternative, of your not being able to depend on us, of your not being treated like a member of the Polestar family. Do you understand?”

Cate understands all too well. She hires a pathologist to examine his body. She urges her family not to take the money. And when the pathologist tells her that Eric didn’t die from the fall itself, she uses her international contacts from her job in the art world to arrange for someone in Cairo to meet her and help navigate the “system”, whatever that turns out to be.

In Cairo Cate meets a gay man named Omar, who is the nephew of Cate’s work contact in New York. He’s initially leery of getting involved too deeply—being gay in Egypt isn’t particularly safe, and when mixing in an entity like Polestar, as Cate tries to explain her mission, Omar says, “Yes, but what I mean is – and please don’t take offense – what difference will it make? They are arms dealers. They control the world. They are best friends with my country. In fact, they probably help run my country. I don’t see what good can come of it …. You should be careful about asking questions here. I am scared of the police. I am genuinely frightened of them every day. You should be scared too.”

Bollen spins a potent mix of the startling—and most reasonable—paranoia surrounding Polestar’s surveillance of their employees, and the seeming futility of an outsider in Cairo finding the truth about Eric’s death. Danger to Cate and Omar increases as Cate delves deeper into the mystery of Eric’s work as a tech, and Polestar’s omniscient presence in his life.

Why choose the arms industry? Bollen explains:

“As I was researching arms sales for this book (and I should stress that even after all my long pandemic-months research into the trade, I’m very far from being an expert), someone remarked that the only business more dangerous is drugs with cartels. That sets a pretty high bar in terms of brutality and mysterious back-channel dealing, even among very legal “upstanding” corporations in the U.S. In fact, one of the reasons I chose for Eric Castle to be a tech instead of a corporate professional, was to lend the situation a grittier, more graspable realism—i.e. not this glamorous mysterious persona of the international arms dealer (although they do actually exist). It began because there have been cases of defense workers killed overseas, mysteriously, with strange cause of deaths that didn’t quite add up. And what really interested me was the way a family really has very little recourse when someone dies overseas. Their laws are the law.”

And, of course, because Eric comes from humble working-class roots, it’s easier to dismiss his death and keep it hidden. He has no power. I didn’t want this story to feel gauzy and romantic, or to end up glorifying the very industry I was out to critique.”

There is an unsettling scene later in the story that also illustrates the powerlessness of the family, as Cate confronts a State Department lackey whom knew Eric, asking in so many words, what can I do to find out what happened? How do I find out who killed him? The answer isn’t reassuring, but it is blunt: “There’s nothing you can do but swallow it. …I say this with your best interest at heart. We’re all expendable. You, me, your brother, every single Polestar employee, that man selling food on the corner, even the president of Egypt, if tides and interests change. We’re all a bad headache that can be gotten rid of in a few days. …You seem like a well-meaning person and I’m sorry for your loss, but you aren’t wanted here.”

Some of Bollen’s previous novels have also been set-in far-flung locations – including Venice and Greece. (Long Island, not so much!) Place as equal character – not always an easy thing to blend a country or city with humans and have them all feel … balanced. But Bollen manages it. Cairo does function as more than simply background.

When asked about the vibrancy of Cairo’s portrayal, Bollen replies:

“Egypt. Since I was a kid, I was obsessed with Egypt. I had piles of Ancient Egypt books—and yes, I had a Death on the Nile movie poster on my bedroom wall in middle-school, and no I didn’t have many friends. … I finally visited in August 2010, the year before the Arab Spring when Mubarak was still in command and fell in love with it just as I suspected. Cairo, Sinai, Alexandria, Siwa. I knew I wanted to set a book there. It comes over me, a certain place. There are so many mesmerizing locales, but they don’t feel quite like a novel I want to spend a year or two pulling inside out. But Cairo was a rare city with a hundred different worlds within a single block … But for me, anyway, places and locations aren’t passive features. They are active characters, perhaps the main character, with moods and irritations and surprising acts of generosity and petty injustices and the rest. So, I try my best to capture that as best I can.”

Plotting out a complex thriller like The Lost Americans has got be tricky as hell. What process works for Bollen?

“I never know where I’m going. And I seem to know less and less the more books I write. And I will say, each book comes to me differently. I have an inkling of an idea of the twist early on, which I try to hold onto. But to be truthful, it’s so all-consuming in my head, that I often stop at the end of the scene and know basically what the next scene should be. Then I’ll be shopping for vegetables or getting a cavity filled or running after the bus and suddenly, in a flash will see how the next scene could play out. So lately, that’s me: two scenes ahead are about all I’m capable of.”

Omar, a pivotal protagonist in the character triumvirate, becomes as crucial to the story as Cate, and Eric in absentia. (While Eric and Cate’s various family members do play important roles in the story, they don’t feature with the same immediacy and prominence.) Bollen describes him this way:

“With Omar, who was really my favorite character to write, there was no question from the beginning that he would be gay. But with that decision came consequences and constraints, and I couldn’t ignore the war that Sisi (the post-Mubarak strongman) and his government were waging against the LGBTQ community.”

As the story evolves, the reader begins to feel both a kinship with Cate and Omar, who also bond in unexpected ways. No, there’s no romance, but, offers Bollen:

“Thinking out loud here, … perhaps Cate and Omar are personifications of nations that are friendly allies? They both want something from each other, they both can be helped by the other to further their individual goals, and yet there is genuine respect and platonic love that grows between them. I don’t think that they become soul mates, or best friends for life, and yet they get each other, they can see a sliver of themselves as a lost character, as outsider in a family. And thus, they begin to feel the need to protect each other. I really enjoyed writing their scenes together. Sometimes you put two people in a scene and think, oh Christ, they really have nothing to say. I felt a weird, reticent bond between them that came naturally.”

So, what’s next? More crime? More distant locales?

“Snailing along on a new novel, I dream one day of slaloming. But it’s not my natural speed. Well, Since I wrote The Lost Americans, while waiting for the edits, I decided to write a short horror story set in Luxor, Egypt (where the Valley of the Kings is), down the Nile. Somehow that little horror took on its own life and I ended up writing a short horror novel. Coming up with a title is something else and it’s not yet been sent out by my agent. Now I’m working on a novel set in Paris, about a young American, a male prostitute in Paris, who gets wrapped up in a murder. It’s basically the opposite of Emily in Paris.”

The Lost Americans is engrossing, expertly conceived and executed, but it’s also disturbing – as it should be. It solidifies Bollen’s stature of a literary crime writer – for many readers, the best kind.

***