School field trips. Exhibitions. Guided tours.

It might be easy to dismiss museums as stuffy or even boring, but they are far from that—especially to an aspiring crime writer looking to write her first murder mystery.

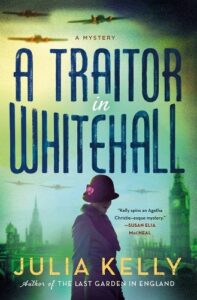

The idea for my debut historical mystery, A Traitor in Whitehall, came to me while standing in the middle of the Churchill War Rooms (formerly the Cabinet War Rooms or CWR). Part of the Imperial War Rooms, the CWR is a unique museum that offers an incredible in-depth look at what living and working would have been in the underground bunker that once served as the top secret nerve center for the British Government during World War 2.

I’d already been to the CWR before, but I was happy to tag along with a friend as she wandered through the maze-like museum that recreates Churchill’s bedroom, the map room where the Allies plotted the course of the war, and the cabinet room where ministers would meet. While she was taking in the exhibition signs, a thought struck me: “This would be the perfect place for a murder.”

Morbid though that seed of an idea might seem, for a historical mystery writer it was like hitting the proverbial jackpot. That’s because museums are wonderful about preserving, distilling, and distributing information about their subject, which is precisely what an author needs when bringing the past back to life.

In A Traitor in Whitehall, my amateur sleuth Evelyne Redfern is a dedicated reader of detective fiction from Agatha Christie to Dorothy L. Sayers. When she is plucked out of the munitions factory she’s working in and reassigned to be a typist in the CWR during the height of the war, she finds herself plunged into Churchill’s hectic world. However, things become deadly when Evelyne stumbles over the body of one of her fellow typists and is forced to use all of the tricks she’s learned from her favorite books to find a murderer and stop a dangerous mole leaking vital information that could cost Britain the war.

When I began to write A Traitor in Whitehall, I didn’t know where the story would take me. However, as I learned more about the CWR, the pieces began to fall into place. The idea for the crime scene, a sunlamp treatment room, came directly from my visit to the museum where I learned that staff were given regular doses of UV light to keep them healthy while working long shifts underground. My victim, a much-disliked member of the CWR’s typing pool, was one of the women who might have worked at one of the six desks still set up in the typing pool. And Evelyne was inspired in part by the many interviews and recollections of enterprising young women who worked at the CWR and whose words punctuate the exhibition space.

However, it wasn’t only my visit that proved vital to writing A Traitor in Whitehall. From the very beginning, I leaned on the museum catalog Secrets of Churchill’s War Rooms by Jonathan Asbury to bring the world of the CWR to life with detail. Through it, I was able to recreate what working in the underground bunker might have been like. I discovered that staff worked in shifts that lasted days, taking breaks to sleep in the Dock. This dormitory-like space, which was lined with bunk beds and fitted with unappealing sounding chemical toilets, became a place for Evelyne to discover clues, test alibis, and generally gather information about her fellow typists who let their guard down around her because she was one of them. Similarly, the Cabinet Room where Churchill and his ministers would meet features in both my book and the museum catalog.

How my characters would move around the CWR was its own challenge, but fortunately the museum has maps, accounts, and artifacts to help fill in the gaps. The secret bunker was accessed through New Public Offices on Horse Guards Road, across from St. James Park. (A testament to how real that setting is, in September 2023, St. James Park had to be evacuated because a tourist discovered an unexploded World War 2-era grenade.) Staff would traverse Staircase 15 to reach the ground level, and accounts of people who once worked there mention how busy the main corridor could be when there was “a flap on.”

To add texture to the story, I looked at museum artifacts such as the bright orange passes that workers had to carry to make their way past the Royal Marines stationed at various points through the building. These guards even became a useful tool in helping Evelyne confirm the alibis of several suspects.

Through my research, I learned that Churchill’s own peculiar preferences shaped life in the CWR. Whenever Evelyne enters the typing pool, she isn’t met with the clattering of typewriter keys we might expect because Churchill couldn’t abide working in a noisy environment. Instead, he had special Remmington typewriters imported from the United States, and typists and secretaries across the CWR transitioned onto these machines.

However, A Traitor in Whitehall isn’t confined to the world of the CWR. Set at the beginning of September 1940, Evelyne and her fellow typists find themselves plunged into the horror that is the Blitz in the immediate aftermath of the murder. Starting on September 7, 1940, and ending the following May, the Luftwaffe hammered London with bombs in an attempt to take out key military and civilian locations and decimate British morale. It is estimated that tens of thousands of civilians lost their lives or were injured, and two million homes were destroyed across the country, with 60 percent of the damage happening in London.

The danger and fear that the Blitz brought to London is part of life in and out of the CWR in A Traitor in Whitehall. The staff living in the Dock become more and more edgy as they wonder if their loved ones and homes have survived, and when Evelyne emerges above ground she finds that the city she loves is in tatters. Bomb damage took out entire roads, while others caught on fire due to the incendiary bombs the Germans also dropped. The air raid siren, which had been a hallmark of London life since a false alarm sounded the morning war was declared, now governs everyone’s life in the capital city, at one point stalling Evelyne’s investigation overnight.

Historical mysteries shine when there is a balance between the puzzle at the center of the book and the historical detail that brings that world to life, and it is the incredible work of museum curators and staff that often make doing that research possible.

***