In visions of the dark night

I have dreamed of joy departed—

But a waking dream of life and light

Hath left me broken-hearted.

–A Dream by Edgar Allan Poe

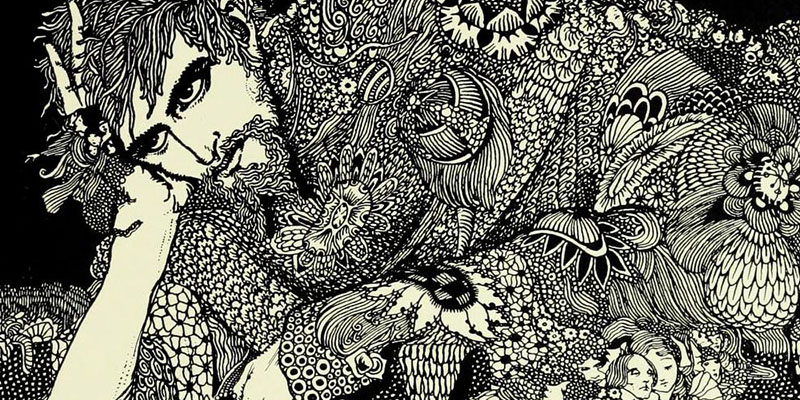

Even before relocating to Baltimore in the summer of 1978, I was an Edgar Allan Poe fan. In my Harlem boyhood I’d seen the Roger Corman films on Creature Features, devoured The Raven when I was twelve and drooled over the drawings Berni Wrightson did for his brilliant “Black Cat” adaptation in Creepy #62 ” (Warren, 1974). Though I’d visited Aunt Charlotte and cousin Marie in Baltimore a few times since childhood, I never dreamed that the city where my literary hero died in 1849 under mysterious circumstances would become my new home.

Two weeks after getting off the Greyhound bus at the old Howard Street depot, I was the new kid at Northwestern High. It was my sophomore year, but it had been a decade since I last attended public school. Shy and nervous, I spent most lunch periods in the library. Having gone to Catholic school for years, I wasn’t used to the unruliness of the cafeteria or the smoking in the courtyard; the library provided the perfect reprieve from the rowdiness.

Besides me and the two librarians, the large room was usually empty. Sitting near the windows, I enjoyed the solitude and read books, magazines or comics I brought from home. Having turned fifteen that June, I was into the weird fantasy of Harlan Ellison and Ray Bradbury as well as Heavy Metal comics drawn by Jeff Jones, Howard Chaykin and Richard Corben.

After Christmas break a new face appeared. The interloping stranger was a pretty light-skinned black girl who looked nerdy in comparison to the very grown-up looking female students at our school. She was ghostly pale as though sunshine had never been her friend. Sneaking glances over the tops of our books, we saw each other every day, but were both too shy to speak. While a few of my best friends were girls, I didn’t know how to approach strangers of the opposite sex without stuttering and sputtering.

Finally, after two weeks of silly behavior, I pulled together enough nerve to approach her. Extending my hand across the table, I said, “Hi. I’m Michael.” Slowly she looked up from her paperback and smiled. Dressed in jeans, a thick flannel shirt and red sneakers, there was a small beauty mark on her left cheek that was darker than her skin and shaped like a discolored cloud.

Taking my hand, she gently shook. “I’m Linda.” On the table was her army knapsack covered with punk rock group patches. I slid into the chair on the other side. “Are you new here too?” She nodded. “Yeah, I went to private school before.”

“Dig that. I moved here from New York in August. I don’t know why, but I’m sure there was a reason. Parents aren’t always big on explaining things.” Linda grinned as though she understood my dilemma perfectly.

“Where do you live?”

“I’m way down on Monroe Street near North Avenue.”

“That’s far.”

“I use my aunt’s address. She didn’t want me to go to Douglass. Where do you stay?”

“My mom and I live on the other side of Reisterstown Road, down the block from Lake Trout place. We’ve been there for a while.” Linda and I talked until the bell rang. My next class was English, taught by Mrs. Sommer, where we were in the middle of reading Beowulf.

As much as I hated pulling myself away from my new friend, that was my favorite class. “I’ll see you tomorrow. Same Bat time, same Bat station.” Again she smiled, but I felt like a goof the rest of the day for quoting the tagline from Batman.

Thankfully, Linda didn’t mind my corniness and, in the days that followed we became fast friends. After school we often went to the Reisterstown Plaza Mall and then I’d walk her half way home, though she insisted that I not escort her to the door. “I don’t want my mother to start bugging out if she sees me with a boy,” Linda explained. “She thinks all men are dogs, even if they’re just boys.”

Most mornings, I couldn’t wait to get to school. First period was journalism followed by homeroom, humanities and biology. I was a good student, but sometimes I drifted while staring out the window at the falling rain, a bag blowing across the grass or a slowly driven car cruising down the street; and I thought about Linda.

Surprisingly, we didn’t share any classes nor did I run into her in the hallway. In retrospect that was strange, but at the time I was simply grateful to see her during our 12:30 to 1:15 lunch break. I usually arrived first and waited patiently for her. I had the same amount of cool as a frantic tail wagging dog awaiting its master. When she finally walked through the door I didn’t bark or lick her face, but my stupid smile said it all.

Three months after we met, on an early spring April day, Linda came to the library wearing a long sleeved black t-shirt, jeans, sneakers and a denim jacket. Carrying her book-bag, she came over to our table. “Let’s get out of here and play hooky for the rest of the day,” she blurted as though the idea had just come to her.

When I went to Catholic school a disappearance from class was noted and followed up with a phone call to your parents. Yet, free from more than the mandatory uniform, those rules no longer applied. “I’d like that,” I said. “I’ve never done that before.”

After stashing our textbooks in my locker, we left by the side door and kept walking until we reached the bus stop. “Now what?” I asked. Linda laughed. “I’m going to surprise you?” We boarded the bus that came and walked to the rear. Sitting next to one other, Linda gave my hand a squeeze. “You can’t cut class with everybody, but I feel safe with you.”

Embarrassed, I mumbled “thank you,” and quickly turned away. We transferred to another bus at Park Heights and Cold Spring. Minutes later Linda asked, “Have you ever taken acid.”

“Acid? Me? Naw. Hell, I just smoked my first joint a year ago. I didn’t think I was ready for acid.”

“I’ve been doing it for about a year. It’s great.”

“I once talked about it with my uncle who told me he used to trip when he was in Vietnam. He said, ‘Just try not to bring too much heaviness into it and you’ll be cool.’ I trust his knowledge.”

Linda reached into her pocket and pulled out a brown pill bottle. After snapping open the lid, she shook out two tabs imprinted with Mickey Mouse clad in his Fantasia/Sorcerer’s Apprentice outfit. “Let’s trip together,” she said. “Open your mouth.” While I’d never opened my mouth for anyone except my doctor, I closed my eyes and stuck out my tongue.

Instantly I tasted the bitterness of the chemically laced paper as it dissolved, taking me closer to Wonderland, Oz or whatever mystical world awaited. In my brain the opening riffs to “Purple Haze” played. Having seen the LSD episodes of Dragnet, where drugs resulted in the taker doing nutty things while hallucinating, I was scared, but I kept that fear to myself.

Fifteen minutes later, Linda reached up and rang the bell. We got off and began to walk. “You ok?” she asked

“I’m fine. Just waiting for the ball to drop; where are we headed?” Linda pointed across the street to a building that had a fancy sky blue sign that read Ice Land. “We’re going skating? I haven’t been ice skating in years. My mom used to take me, but it’s been awhile.” Seconds later, as I stepped through the door behind Linda, I felt the first tingle of highness.

The rink had just opened and we were the first customers. We rented skates and went to the changing area. From where we sat there was a clear view of the rink where there were strobe lights overhead and a DJ deep into spinning disco grooves and creating a soundtrack for the skaters. “I’m not really into that kind of music, but it sounds good when I’m in here,” Linda said.

As we stepped onto the ice, the acid kicked in like Bruce Lee’s Chinese Connection as Foxy’s soulful pop “Get Off” pumped from the speakers. The colorful strobe lights were intense, but we were never far apart. Usually I was afraid of falling and shattering my nose on the ice as blood stained the smoothness, but the acid gave me the courage of Dorothy Hamill.

For the next two hours we had the Ice Land to ourselves, but when a local hockey team came in at four o’clock we knew it was time to leave. “Let’s go to the liquor store and get a bottle of Jack Daniels,” Linda suggested. “Then I have someplace cool for us to go.” Back then the drinking age was eighteen and no one ever asked for ID. We got the booze and two plastic cups from a spot called People’s Liquors.

Trekking a few blocks, we reached a wooded area and Linda led me to a dirt path that we followed for half a mile as the sun began to set. There were many trees with skeletal branches reaching out in the darkness. Most were bare, but a few were beginning to bloom. “I’m glad you’re not a crazy killer,” I joked.

“How do you know I’m not?”

“Don’t joke like that, I scare easily.”

- Courtesy the author

- Courtesy the author

Linda laughed wickedly. Suddenly she stopped walking. “We’re here.” To the left of me was a waterfall running into a small lake. The woods were dark except for the area where the full moon shone on the water. A dead tree lay on the bank. We sat down and poured ourselves a drink.

“This is my special place. I used to come out here a lot when I ran away from home. You’re the only person I’ve ever brought out here.” We toasted and gulped the brown liquid that burned as it went down. In the darkness frogs, owls and other nocturnal creatures made their night noises.

Gently, I held her hand before extending that into a hug. I spotted a deer standing behind the trees staring at us. It was a protective look as though the animal was prepared to defend Linda if necessary. Though I was nervous, I moved closer, kissed her soft lips and tasted heaven.

A half hour later we sat on a bench at the bus stop. Linda smiled when a shopping cart pushing derelict stopped in front of us. “You missed the last bus,” he said. A strong smell wafted from the man’s body. Dude smelled like death. “Thank you, man,” I replied. Turning to Linda, I shrugged.

“I suppose we can walk,” she offered.

“Walk?”

“Yeah, you know…one foot in front of the other.” We started on a journey that took almost two hours. Though I had no idea how to get to her house, Linda seemed to have taken that before. Many of those blocks had dim street lights. There were bikes discarded on lawns and the murmur of voices, both real and on television, were heard behind the doors and windows.

Linda and I talked about many things including our mutual love for the Harry Nilsson cartoon The Point, our difficulty interpreting Shakespeare and the general spookiness of Baltimore, where, while standing on a Charles Street bus stop weeks before, a large bat flew from the window of an abandoned building and into my face. “Then there are the rats. I’ve seen rats the size of cats. It doesn’t help with all the digging up of the streets the city is doing to build the subway.”

“I’m sure there are rats in New York.”

“Maybe. I’ve never seen one there. Our subways are already built.”

“So they are.”

“Well, in the City of Poe I should expect creepy, strange stuff to happen here.”

“Baltimore is an old place,” Linda countered. “Like Nina Simone sang, it’s a ‘hard town by the sea.’ Do you know her music?”

“Not really.”

“Well, I’ll have to make you a mixtape then. Can’t have you going around not knowing Nina Simone’s music.”

It was after midnight when we finally reached Lisa’s house. “What a night, huh.” We both laughed until a light clicked on in an upstairs room. “That’s my mom. You better get on the road before she comes down. Thank you for a wonderful day and a beautiful night.”

With me living on the other side of town, there was another walk in my future. Luckily the streets of Baltimore were safer back then, the only thing I feared were the rats. A city of alleys, and I passed a thousand on my long journey home. I also walked by takeout Chinese spots, record shops, liquor stores and Cloverland Dairy. Above me the twinkling stars were bright.

Reaching my Monroe Street row house at 2 AM, I stumbled up the marble stairs. Mom was already at the front door waiting and screaming about my lateness. “Do you think you’re grown? Do you think you’re grown?” she screamed. “You got me up at all hours of the night, could’ve at least called.” She slapped me on the shoulder.

“Come on, mom, I’m tired. Can we do this tomorrow please.”

“Don’t think you’re not going to school tomorrow either.”

I went by and slowly dragged myself upstairs to my room. That night I laid in bed staring at the ceiling and thought about what could’ve happened, the possibilities of our friendship developing into something deeper.

At school the next morning I sat in the library at lunch period awaiting Linda’s arrival, but she never showed. I was thrown off for the rest of the day. The following afternoon I went to Reisterstown Plaza to look for her at our regular haunts that included the record store and Waldenbooks.

The last time we went book shopping, Linda bought the angst girl’s bible The Bell Jar. “I had an old copy that belonged to my mother, but the pages were so brittle they were turning to dust every time I turned them.”

After coming up with zero, I bought a frozen yogurt with banana chips. Walking down Reisterstown Road, a bus passed and I spotted Linda sitting in the rear. Rushing to the front door, my heart raced. Making my way to the back, I looked around, but she wasn’t there. Sitting in the exact seat I thought Linda was occupying was a grammar school child whose big, sad eyes reminded me of a Keane kid.

A wave of sadness overcame me as I exited through the back door. Upset, I walked for blocks muttering to myself and feeling a headache beating between my ears. I stopped at the House of Pancakes and had a big breakfast for dinner with a few cups of coffee.

An hour later I boarded another bus. Not paying much attention, I was making my way to the back when someone said, “Michael.” I abruptly stopped walking, gazed in the direction of the voice and saw Linda sitting next to the window. “Are you going to sit down?”

I sat next to her and looked at her face. There were dark circles beneath her eyes as though she hadn’t slept in a while. “Where have you been?” I’ve been going out of my mind looking for you.”

“Really? I’m sorry. It’s been crazy around my house.”

“Oh, shit. What happened?”

“It’s nothing I can talk about right now.” She pulled a small writing tablet out of her purse, scribbled a number and gave me the paper. “I’m going to be staying with my grandma for a while. Call me over there.” For the next few minutes the silence between us was maddening. Suddenly Linda rang the bus bell and stood-up. “It was good seeing you, Michael. You call me, OK.”

“I will. I promise.”

However, while I kept my word, the phone number she gave me simply rang and rang and rang. It was as though she’d vanished, disappearing in a puff of smoke. Part of me began to question Linda’s existence. It wouldn’t be the first time a lonely boy created an imaginary friend. I cursed myself when I realized I didn’t even know her last name or address, which made looking for her a lost cause.

A few weeks later I bought the Nina Simone album Baltimore and played the title track. I was surprised when, while reading the liner notes I saw that Randy Newman had written the song, which was first placed on his 1977 album Little Criminals; the same disc where the infamous hit single “Short People” also appeared. Newman’s version was more melodic, damn near as noir as the city itself.

Meanwhile Simone’s upbeat reggae sound that was the idea of producer Creed Taylor mixed with soaring violin strings, was more hopeful. Even when she sang, “Oh, Baltimore, ain’t it hard just to live?/Oh, Baltimore, ain’t it hard just to live? Just to live,” I had a sense that things would get better. Though I didn’t know it at the time, the year that we met (1979), Jamaican production team Sly and Robbie produced a real reggae version of “Baltimore” for the Tamlins as well as a dark dub version.

By the end of the school year I finally made a few friends, became less fearful of my surroundings and began hanging in the lunchroom more. The following semester, in 11th grade, I was down with several school cliques, had developed friendships with some of the popular kids as well as the arty (visual and band) crews, a few sci-fi nerds and even a few jocks.

As for Linda, she never returned to Northwestern. It was as though she was some kind of spirit, a specter sent to help me transition into my new life in that old city. More than four decades later she’s still on my mind, especially when “Baltimore” pops-up on my Spotify playlist and I hear Nina Simone (or Jazmine Sullivan) singing about that broken winged bird, that, “Beat-up little seagull on a marble stair/trying to find the ocean, looking everywhere.”