You never forget your first… Great Illustrated Classics. For me, it was Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea—a thick (or so it seemed to a seven-year-old), white-spined hardback with a slick blue cover, large print on rough cream paper and pen-and-ink illustrations that took me from a casual reader of Choose-Your-Own-Adventure paperbacks to a connoisseur of the classics. Never mind that the description ‘abridged’ was a gross understatement. With Jules Verne followed by H.G. Wells, Alexander Dumas and Jack London, I fell hard for not only the classics, but for the genre of 19th-to-turn-of-the-century adventure fiction.

Despite being part of the 66-book Classics collection, I had no interest as a child in picking up Heidi, Black Beauty or Little Women. Instead, I read and re-read the stories that flung me to far-off places and mired me in impossible situations. I plotted out how I would have escaped from Château d’If and longed for a pet wolf I could name White Fang.

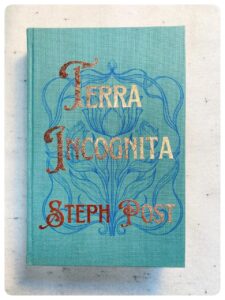

Eventually, of course, I moved on—from mysterious islands and journeys below ground to dragons (Anne McCaffery’s Pern dominated my eleven-year-old imagination)—but I never forgot those first adventure classics. Of course, later, I loved the full, unedited versions of the novels as well, and looking back now, I can see clearly the threads of all those stories that eventually wove themselves into the fabric of my latest novel, Terra Incognita.

Set in the late 19th century, Terra Incognita—grounded by a famous explorer’s obsessive quest to find the last lost city—checks more than a few boxes when it comes to classic adventure fiction. Danger faced in every new locale visited, a trail of mysterious artifacts, a kidnapping, a chase, a heist! But one of those checks goes far outside the box: the main character of the novel, Lily, is a woman.

Not only do classic adventure novels focus only on the adventures of men, oftentimes the few female characters—if they even exist—serve as mere props or token. In all honesty, though this fact rankles me, it doesn’t detract from my love of certain epics. One of my favorite films of all time is Lawrence of Arabia and over the course of 227 minutes, not a single female speaks. And despite Liv Tyler’s Eowyn in the Peter Jackson films, there are only two female characters who speak across the thousand-or-so pages of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

Of course, die-hard fans love to point out that “it doesn’t make sense” for women to be in any of these stories. I’m not going to go down the rabbit-hole of why I think the anachronism argument is meritless—I could be here all day—but in looking at how Terra Incognita would hold up against my beloved adventure novels, I realized that, in all reality, the authors had missed so many opportunities for rich storytelling by excluding or diminishing women.

In the spirit of going all the way back to those germinal Choose-Your-Own-Adventures, then, here’s a few examples of how I would have jumped on those opportunities.

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne

Of course, I had to start here. Twenty Thousand Leagues has everything—sea monsters, ice barriers, giant squid, a visit to Atlantis, claustrophobia and paranoia, obsession and melodrama, a dark, brooding anti-hero on a blind path of vengeance—except even one female character. Like Penelope to Odysseus, Captain Nemo’s unnamed wife is the motivating force that delivers for us the “archangel of hatred,” but, unfortunately, she’s dead. The image of Nemo crying in front of the portrait of her with their two, also dead, children is deeply haunting in the most tragically romantic way. While the Captain alludes to righteousness and an abhorrence of oppression and imperialism to rationalize his vendetta against civilization, it’s obvious that his family is the true motiving factor for his murderous desires. Perhaps Nemo’s wife has more in common, then, with Helen of Troy.

But aside from the fact that she’d dead—by way of the “oppressor”—and was young at the time the portrait was painted, we know absolutely nothing about the wife whose face doesn’t launch ships, but sinks them. Just think of what Verne could have done with her! Structurally, she could have been the impetus for flashbacks scattered throughout the text. I mean, what kind of woman would have married a man like Captain Nemo? Perhaps she was an adventuress herself, or a revolutionary. She could have been an heiress and an engineer, whose fortunes and talents designed the Nautilus that Nemo retreats to upon her death. Was she faithful to him? And he to her? To throw in some extra drama, Nemo could have discovered with her a lover, cursed her and abandoned her. He vanishes to the high seas and she drowns herself and their children. Nemo then wallows in guilt for the rest of his life and succumbs to the Maelstrom with his wife’s name on his lips. Sound too dramatic? I don’t want to hear it. Jules Verne gave us the everlasting image of Captain Nemo sobbing and playing the organ in the dark—nothing could be too gothic or romantic after that.

Truly, though, I’d love nothing more than to add in a surprise twist. Captain Nemo’s wife faked her death to escape his obsessive ways and we meet her on the very last page. We learn that the entire framework of the novel is actually Aronnax recounting the tale, fireside, to Nemo’s wife. Better yet, the wife is on board the Nautilus the entire time! Captain Nemo loves her, but has kept her prisoner and when the Professor and Ned Land unwittingly free her she exacts her revenge…

The Time Machine by H.G. Wells

Okay, I’m stopping myself before this piece devolves into nothing but Captain Nemo fanfiction. Let’s try a few others. The Time Machine was another childhood favorite, with Wells’ depiction of the subterrain Morlocks fascinating me to this day. Wells does better than Verne when it comes to female representation, but then, we’re talking about a novel where the protagonist is referred to only as the “Time Traveler” and the other defined characters are comprised of the likes of the “Editor” and the “Doctor.” Our single female character is, at least, the only named character, but I’m not sure that this makes up for the fact that Weena still has no speaking lines.

As one of the Elio, Weena is both revered and infantilized—the perfect damsel in distress for the sanitized utopia the Time Traveler first believes the future to be. Of course, things take a darker turn when he discovers that the Elio are mere fodder for the Morlocks, but Weena does have a prominent stage presence throughout the second half of the novel as she accompanies the Traveler on his descent into the underworld to recover his time machine. Unfortunately, a presence is as far as it goes, and though the Time Traveler can apparently speak her language, Weena herself never speaks. Her sole agency in the story is putting flowers in the Traveler’s pocket, which helps to prove his case that his story is true.

Whether Weena is to be considered as an adult or a child, I think it would have been fascinating for Wells to given her a voice. Since she’s physically present during the most exciting parts of the novel, it seems such a waste that she does nothing more than let herself be carried around by the Traveler like a piece of luggage. The very climax of the story involves her capture and—insinuated—end as a Morlock meal, but we never even hear her screams. She simply vanishes. In my version of The Time Machine, Weena is wise and guides the Traveler instead of simply being dragged along, and we learn so much more about Wells’ speculation of the future. Giving her agency in her own demise would add something that, unfortunately, is lacking in what is otherwise a brilliantly imaginative tale: emotion.

A Princess of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs

I wanted to end with Burroughs’ first novel in what would become an 11-book series chronicling the swashbuckler John Carter and his many adventures on the planet Mars, because I just recently read it for the first time. Burroughs was writing later than Verne and Wells, but he brought in a new wave of adventure novels for the first half of the 20th century. While often dismissed as science-fiction pulp, the Martian (or Barsoom, the given name of the planet in the books) Series fits right in with its preceding classics.

John Carter is the quintessential male hero—the strongest of the strong and bravest of the brave—who bounces from one close call to another while journeying from Earth to Mars and back again. Like most adventure novels, A Princess of Mars is episodic and in the vein of Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo, there is a love story spurring our un-killable hero on. Dejah Thoris, the titular Princess of Mars, is a developed character who makes choices for herself and has something of a personality, but for the most part she spends a lot of time being kidnapped or maltreated by the brutish Tharks, giving Carter one opportunity after another to put himself in peril by rescuing her. (She also, in the tradition of sci-fi pulps, gives illustrators a reason to include a busty and mostly naked woman on every cover.)

But, surprisingly perhaps, there are two other females named among the hoards of Red and Green Martians and I would have loved for Burroughs to take the character of Sola further. She’s so close having real agency in the novel. The daughter of the great Thark war leader Tar Tarkas, Sola teaches John Carter the Martian language and ways, and fights for both Carter and Thoris, even against her own people. She’s the carrier of one of the great secrets of the story and shows real growth and change as the events of the novel effect her in different ways. And she’s not a love interest. How about that?

But Burroughs gives up on Sola there. Once she vows to forever serve the Prince and Princess of Mars, her character stalls. She devolves into a two-dimensional martyr who fades into the background as a sort of handmaiden. If I had my way, Sola would have followed in her father’s footsteps and become leader of the Tharks in her own right. She would have avenged her murdered mother and then gone on her own adventures, maybe even eventually challenging her revered John Carter—with ten more novels to follow, there’s plenty of room for her to stretch.

Of course, the genre of adventure novels has grown and changed since the heyday of Burroughs and female characters are becoming more common, though sadly they often don’t make it past the fates of Sola and Dejah Thoris. YA and memoir have come to dominate what was once closely linked to fantasy and science fiction and—gasp!—women are producing some of the finest works in these genres today. This, then, is a reminder of what should have been obvious all along: the women are there. Their stories take up as much as space as their male counterparts. They just need to be written.

***