Wales is a country with a distinctive and fascinating character. A land of mist and mountains, of myths, magic—and mystery. The close geographical and historical association between Wales and England, coupled with the bilingual nature of Welsh literature, contribute to the unique flavour of Welsh writing. Today, Welsh literary culture flourishes, with a celebrated annual festival held at that wonderful book town Hay-on-Wye. Its history is equally impressive, dating back to the sixth century and encompassing the Mabinogion— wonderful medieval folk tales—as well as the work of poets such as Dylan Thomas and R. S. Thomas, and writers as notable as Roald Dahl, who was born in Cardiff and achieved success in two very different fields: children’s fiction and macabre “tales of the unexpected.”

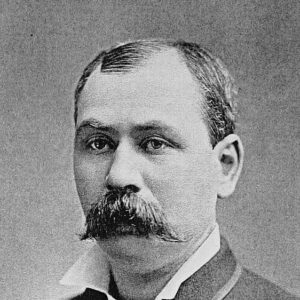

Macabre fiction has been a particular strength of Welsh writers over the years, perhaps in part inspired by the alluring yet sometimes eerie quality of the landscape. Arthur Machen was a master of this form of writing, while another of the authors featured in this collection, Cledwyn Hughes, wrote a good many interesting weird stories which deserve to be rediscovered. Emlyn Williams, the playwright and actor most famous for the psychological thriller Night Must Fall, often worked on the boundaries of crime writing. Until relatively recent times, however, Welsh authors of conventional detective fiction have been few and far between—so, perhaps surprisingly, have crime stories set in the country, whether or not written by Welsh authors.

The “Golden Age of Murder” between the two world wars, for instance, can scarcely be claimed as a Golden Age for detective fiction set in Wales. The Great Orme Terror by Garnett Radcliffe (an Irishman) has a promising title which refers to a rocky promontory close to Llandudno on the north coast of Wales. The story is, however, pulpy and lurid. On his arrival in the area, Dr. Constandos brings news for the lovely young tennis player Mona and her admirer, the monocled Lord Basil Curlew, about golden treasure in a Spanish galleon sunk just off the Great Orme. Mona believes, for no obviously compelling reason, that she has a moral right to the gold, and she and Lord Basil determine to find it. Unfortunately, various villains are also searching for the loot—and they include characters such as a nasty fellow with green fingers known as The Lizard and the mysterious and bestial Gravenant. Superintendent Fibkin is helpless when faced with such devilish adversaries, who have at their command an army of weird death-robots, and will stop at nothing—certainly not torture and murder—to get their wicked way.

More impressive, if still outlandish, are the “impossible crime” mysteries written by Virgil Markham, an American. In Death in the Dusk (1929), Victor Bannerlee is an antiquary travelling in Radnorshire. After a couple of bizarre encounters, he finds himself lost in the fog, and stumbles on an ancient mansion, which just happens to belong to an acquaintance. The house party gathered there for a wedding, is a motley crew, and the sense of impending doom intensifies with the appearance of a bizarre apparition rejoicing in the name Parson Lolly. A non-stop sequence of weird occurrences helps to disguise a pleasing plot twist.

Another Markham mystery, Shock! (aka The Black Door, 1930), boasts a remarkable subtitle: “The Mystery of the Fate of Sir Anthony Veryan’s Heirs in Kestrel’s Eyrie Castle near the Coast of Wales.” A sub-subtitle adds: “Now set down from information supplied by the principal surviving actors, and witnesses.” The first edition contains an elaborate pullout folded family tree of the descendants of Horace Veryan. Some addenda to the tree, although printed, appear to be handwritten, bringing the toll of fatalities in the family up to date. For good measure, a map of the local area, featuring St David’s and Ramsey Island, is included, and there are plans of the ground and first floors of Kestrel’s Eyrie. The viewpoint character is Tom Stapleton, an American who comes to Wales hoping to see Sir Anthony Veryan, recently incapacitated following a murderous attack, only to find himself embroiled in a complicated mystery.

Richard Hull, one of the most innovative exponents of the “inverted mystery” during the Golden Age, had strong Welsh connections, and The Murder of My Aunt (which, like Excellent Intentions, has been published as a British Library Crime Classic) is set in a house modelled on his family home, and the events take place close to a fictional version of Welshpool. The Welsh archaeologist Glyn Daniel adopted the pen name Dilwyn Rees when publishing his debut mystery The Cambridge Murders in 1945. The novel later appeared under his own name, as did his second novel, Welcome Death (1954).

Daniel wrote no more crime novels, concentrating on his academic career at Cambridge, where his pupils included the future crime novelist and critic Jessica Mann.

Dylan Thomas enjoyed (and reviewed) detective fiction, although his novel The Death of the King’s Canary, co-written with John Davenport during the Second World War, is a spoof of the genre brimming with in-jokes which fell rather flat when it was posthumously published in 1976.

A good many English-born writers have an affinity with Wales. This is especially true of those who come from the Welsh Marches (a vaguely defined area which arguably includes counties such as Cheshire and Gloucestershire as well as Shropshire and Herefordshire). A notable example was Edith Pargeter, who wrote many books under her own name before becoming famous under the pen name Ellis Peters.

Dorothy Bowers was born in Leominster but grew up across the border in Monmouthshire. Her five novels showed ability and the promise of future achievement before TB cut her life tragically short. L. P. Davies, who was born in Crewe and who also wrote under the name Leslie Vardre, penned a number of interesting macabre stories set in Wales, while the climber Frank Showell Styles, born in Birmingham, enjoyed success with a series of mysteries written under the name Glyn Carr and featuring Sir Abercrombie Lewker; his titles include Death Under Snowdon (1954).

Perhaps the most successful mystery novel set in Wales during the early post-war period was Cat and Mouse (1950) by Christianna Brand, a contributor to this volume, several of whose books have been reprinted as British Library Crime Classics to widespread acclaim.

Nine years later, Strike for a Kingdom, the first novel of Menna Gallie, was set in Cilhendre, a fictional version of Ystradgynlais, a mining village in the Swansea Valley where she grew up. The story is set in 1926, at the time of the General Strike, and combines a whodunit plot with a picture of tensions within a small mining community. The book was a runner-up (to Eric Ambler’s Passage of Arms) for the CWA Gold Dagger, but Gallie was more interested in politics than plots or puzzles and she did not return to the genre.

Published in 1970, Die Like a Man is an enjoyable bibliomystery from Michael Delving (the pseudonym of American writer Jay Williams), which benefits from a very well-realised setting in south Wales. Book dealer Dave Cannon finds himself stranded there and soon gets mixed up in an exciting, albeit improbable, series of escapades involving an ancient bowl which is claimed to be the Holy Grail.

Welsh-based crime fiction remained relatively uncommon until the latter part of the twentieth century, although some of the mysteries published by the prolific Rhondda Valley-born Roy Lewis were set in the country. In modern times, however, Welsh crime writing has experienced a boom, and bilingual TV series such as Hinterland and Hidden (aka Y Gwyll and Craith, respectively) have also enjoyed considerable popularity.

Against that background, this anthology, like its sister volume The Edinburgh Mystery and Other Tales of Scottish Crime offers a wide range of criminous fiction from an eclectic group of contributors. Some of the stories are written by Welsh-born authors; some are set in Wales; some meet both criteria.

In putting this book together, I have been given a great deal of help by Jamie Sturgeon and others, notably Nigel Moss and John Cooper. Cledwyn Hughes’s two daughters, Rebecca Hughes and Janet Laugharne, supplied me with invaluable material as well as a range of their father’s stories to choose from. Siân Griffiths also kindly discussed the life and career of her father, Jack Edwards Griffiths, with me. I’m also grateful to the members of the publishing team at the British Library for their work in making this book a reality. And finally, a word of thanks to those who read these anthologies and who often get in touch with interesting comments and suggestions; your support and continuing enthusiasm for this series is much appreciated.

_____________________

From Martin Edwards’ introduction to CRIMES OF CYMRU: CLASSIC MYSTERY TALES OF WALES. Copyright ©2024 by Martin Edwards. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, British Library Crime Classics. All rights reserved.