We’re in the kitchen, my mother and I. My mother is crying, as I try to comfort her. My father, still at the dining room table, the outburst having left him spent and, I suspect, embarrassed, is trying to figure out what has happened. And perhaps more to the point: why it has happened again.

The set-up, you see, was always the same. The only question, really, was who was the victim? The person who needled and poked and did what she could to provoke a reaction – or the person who reacted, exploding in a truly frightening outburst of rage and frustration? Over the years, I began to doubt my first reaction, that of sympathy for my mother. I began to question what was really going on.

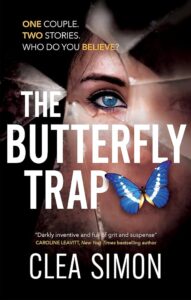

That scene, which recurred repeatedly through my childhood, sparked the questions that are at the center of my new psychological suspense, The Butterfly Trap. Who has power in a relationship? Who sets the boundaries, and who is allowed to break them? And what, ultimately, is the price each party pays?

In my parents’ situation, the lines were, well, almost clear. My father was a doctor, an internist with a private practice who had fallen in love with a beautiful artist and who could promise her a comfortable life. My mother was a doctor’s daughter – a somewhat unwilling medical student when they met, who knew even then what was expected of her. Who knew she was expected to marry rather than support herself.

It was a deal made with open eyes. However, I believe she soon came to find her life constrained. Her career secondary to her role as wife and mother. Part of that was earning power and part was the sexism of the times. The painting and printmaking that she dedicated so many hours to were deemed less valuable than her skills as a homemaker and hostess. Although I spent many hours in her studio, playing with scraps of rice paper leftover from collages and the shells and bits of driftwood that would play into assemblages, I learned this by osmosis. The turpentine used to clean etching plates, the solvents for washing brushes, for washing rags, all had to be put away by a certain point – no matter where the work was, what stage a piece was at, or how close the artist was to her vision. Dinner at six, served by a woman made up as if she hadn’t been toiling all day.

In retrospect, rage was inevitable. As was confusion. After all, wasn’t my father providing for my mother? Giving her everything she could desire? How much of herself did she really have to sacrifice by cleaning up a bit before she was ready? By fitting herself into that dress, mixing the Manhattan? Smiling?

In our generation, the lines have blurred a bit. The arts still pay less than the sciences, but gender roles have become less restrictive, or at least less well defined. This has laid bare other truths – like the way (some) men fetishize women artists, seeing the creative act as sexy. As a mystery, as if we were once again priestesses interceding between the worlds, between birth and death. Or, yes, the way (some) women still look for a man to support them. A finance bro, if not a doctor. Add in the pressure of today’s economy, the lengths some of us will go to pay our bills, to make rent, while still hanging onto our dreams, and you’ve got a situation that may be more amorphous but is certainly no less volatile than what I grew up with.

That’s the setup for Greg and Anya, the two POV characters in The Butterfly Trap. Two people who fall into a relationship, if not exactly love, and whose own desires blind them to the reality around them. There are other characters, of course. No relationship exists in a vacuum, and we’re all more influenced by our friends and colleagues than we admit – especially when we’re first starting out, with all the insecurities and professional jealousies of youth. Add in some willful behavior, some pressure and self-delusion, and the two find themselves in an explosive situation with far deadlier consequences than those teary kitchen confabs of my childhood.

It’s been said (not by me, alas) that we write to understand what we think. I get that. I need to work through scenarios in order to understand them, and somewhere along the way, if I add a few “what ifs” those become a plot. What I would add is that we write to understand how we feel about things. And for this book, I channeled both my pity and confusion, the sympathy I felt for my sobbing mother as well as for my confused father. The sensitive aesthete who had been abused and the bull in the china shop, bewildered by wreckage around him.

Faulkner famously said, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past,” and it is a truism of therapy that all trauma revives and recapitulates the original trauma. For those of us who had tumultuous childhoods, that can mean we relive the hurt in our own relationships, in patterns that we recognize only too late in the game.

If we’re lucky – as I am – it can also mean we have access to the conflicting emotions, the pain and the desire. It means we can work out what happened – what really happened – or what should have, with our characters. Greg and Anya may never have the opportunity to gain that perspective. What happens between them, however, is inevitable. Scripted by who they are, who we are, and the roles that fate has forced them to play.

***