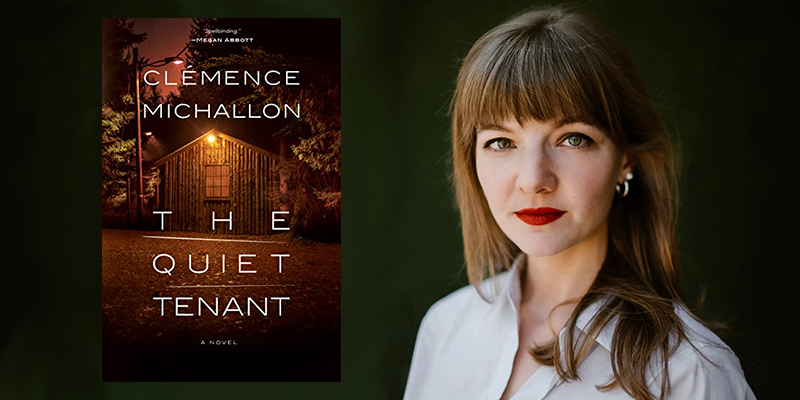

Clémence Michallon is an award-winning French journalist, a dog owner, a New Yorker, and a Sopranos convert/superfan. Her US debut, The Quiet Tenant, which comes out this June from Knopf, is poised to be a major summer blockbuster. The book has been sold in over thirty territories and is garnering comparisons to another famous captivity novel—Room by Emma Donoghue.

The Quiet Tenant takes place in upstate New York and tells the story of three women affected by an active serial killer, Aidan Thomas. At the start of the novel, Aidan’s wife dies, and he is forced to move “Rachel,” the captive in his shed, into his new home. Suddenly, Aidan’s two identities—family man and monster—begin to blur. In addition to Rachel, we hear from Aidan’s teenage daughter, Cecilia, and a local woman, Emily, who is smitten with the recent widower. What emerges is a portrait of one man’s psychopathic duality and the resilience of the women in his wake.

The Quiet Tenant takes place in upstate New York and tells the story of three women affected by an active serial killer, Aidan Thomas. At the start of the novel, Aidan’s wife dies, and he is forced to move “Rachel,” the captive in his shed, into his new home. Suddenly, Aidan’s two identities—family man and monster—begin to blur. In addition to Rachel, we hear from Aidan’s teenage daughter, Cecilia, and a local woman, Emily, who is smitten with the recent widower. What emerges is a portrait of one man’s psychopathic duality and the resilience of the women in his wake.

Clémence’s first book, La Dernière Fois Que J’ai Cru Mourir C’était Il y a Longtemps (The Last Time I Thought I Was Dead Was a Long Time Ago), was published in French, in 2020, with a small feminist press. Clémence and I talked about her journey from reporter to small press author to blockbuster genre writer. We also talked about the ethics of writing violence and—of course—about The Sopranos.

Kate Brody: You have worked as a journalist for many years. Some of your work has covered true crime. How has that reporting informed your fiction? Were there any real-life cases that inspired aspects of this story?

Clémence Michallon: I moved to the US in 2014 to study journalism. I’m a staff writer now at The Independent, a British newspaper, and I still cover true crime in my work. Building a library of personal knowledge is part of the job, but when I sit down to write fiction, I only allow my journalism brain and my fiction brain to communicate as little as possible. I don’t want people to feel like they might talk to me for a journalism piece and then have something end up in a novel.

Crime fiction has a relationship with true crime. I wrestle with the boundaries of that. Some stories aren’t mine to tell. Building a fictional serial killer was an interesting exercise. I knew I was entering a very rich field, and I didn’t want him to feel like a fictional avatar of a real serial killer.

Recently, there was a serial killer called Israel Keyes. He was caught and died by suicide in prison in 2012. An 18-year-old barista went missing in Anchorage, Alaska, and they arrested him for her kidnapping, which later turned out to be her murder. The FBI got involved, and it turned out that he’d been a serial killer for years. We still don’t know how many victims he had or exactly who they were. He was someone who had a job and a family.

Ted Bundy is one of the killers people reference when we think about men who had a mask of normality and managed to keep two separate lives. I thought about Bundy and also about Jeffrey Dahmer and Dennis Rader (BTK). The through line for all three, when people found out about their crimes: we never would have suspected. Bundy’s former girlfriend, who lived with him for years, had a memoir called The Phantom Prince that fed the novel.

Someone living a double life and seeming totally normal, that is the big fear: there is the version of the life that you know, but underneath, there are dark secrets hiding.

KB: One way to look at the book and its multiple viewpoints is to think of it as a study of the fallout from a single bad man. There are so many people—women, especially—impacted by Aidan’s actions. Were there any other perspectives that you thought about incorporating? Did you know from the start you weren’t going to include Aidan’s point of view?

CM: The Quiet Tenant started with only one point of view—Rachel’s—in the first-person, present tense. Rachel’s point of view is essential and gripping. If there’s one point of view that you can’t remove from the book, it’s hers. But it is limiting. We can’t always be in the shed with her. She sees only one aspect of Aidan.

One of the big things I wanted to explore was Aidan’s duality. Sometimes when we talk about people who have double lives, we treat the cruel, violent life as the real one. I wanted to interrogate why we do that. Why can’t we consider the possibility that there is some sincerity in the regular life and in this person’s relationships with their family and their romantic partner?

From Rachel, we get Aidan’s identity as a perpetrator. From Emily, we get how he’s perceived in the town. And from Cecilia, we get who he is as a family man.

I wrote a version of the book knowing I would add Aidan’s past victims later. I think that was another perspective that none of the other characters would have. It’s the true-crime podcast part of this story: what did he do, and to whom? I didn’t want to show him committing a murder, but hearing from the other victims was a way to address that part. And it seemed fitting to show glimpses of their lives, the great loneliness of their deaths, and the unfairness of it all. It helped paint a fuller picture and increase the menace on the page.

With Rachel, the first person never sang. What she describes is dark and painful—too dark and too painful, maybe, to work in the first person. I switched to the second person after reading Lisa Taddeo’s Three Women. She uses the second person in some of her chapters, and I didn’t know why it worked— until I read a piece by Brandon Taylor in Electric Lit, and he said that the second person can be a way to show the fragmentation of a traumatized mind—or, more precisely, “conjure the eerie, oblique angle between a person who has been traumatized and their sense of themself.”

KB: The three sections sound distinct. Cecilia’s voice is very young, and Emily’s version of things is almost like a Hallmark movie featuring a small-town widower.

CM: That’s exactly what I was going for. I was watching a lot of rom-coms when I wrote the novel. Emily’s chapters were fun to write because she doesn’t know. It’s the viewpoint of a woman who’s had a crush on this man forever, and he’s finally paying attention to her. That was the mindset I had to be in to write those chapters.

Cecilia’s voice was the hardest one to nail. Teenage girl is a hard voice. I went voice-shopping for her by re-reading Bonjour Tristesse by Françoise Sagan, a French book about a teenager who spends a summer in a beach town with her father and his two girlfriends.

Teenagers are so smart, but they’re also kids. They can’t understand every single nuance of everything that happens around them. I didn’t want to compromise on that; I really wanted Cecilia to be a kid. Even though I was once a teenage girl, it was hard to access that again, to get back there.

KB: As I was reading, I thought about a friend of mine who recently discovered that the man she was planning to marry was not who she thought he was. He wasn’t a serial killer, but he was basically living a double life. Thinking now about Emily—what is the cost to her of Aidan’s betrayal?

CM: I imagine there are some pages where Emily is a tough sell, but I’ve always had a lot of empathy for her. She’s getting love-bombed and then ghosted in a way that is designed to make her lose the plot. I read somewhere that Ted Bundy did something similar to a woman he’d been involved with. There’s this romantic cruelty aspect, where the cruel temperament can trickle down to lower stakes situations than a murder.

Most cruelty isn’t a serial killer having his hands around someone’s neck. Most cruelty is casual. It’s people pretending they don’t understand what’s going on and acting callously. I thought a lot about the people we forget in these stories. We think about the perpetrator and the victim. But there’s a form of victimization for every relative, every romantic partner who is lied to and has to go on afterward and rebuild their lives.

I’ve always been interested in how things unfold on a granular level. There was a day for Ted Bundy’s girlfriend when he was arrested and never came back. Taxes were still due that year. She still had to care for her daughter. Her job still expected her to show up. And I think that requires the kind of compartmentalization that is not unlike the type that killers deploy.

KB: Do you think Aidan does love his daughter? How is he able to kind of separate these women in his life from those who are completely disposable to him?

CM: I do think Aidan loves his daughter. Love maybe looks different to him, but there are as many different kinds of love as there are people. He loved his wife in his own weird, maladaptive way. We get a hint that a big part of why he kept Rachel alive for the five years that precede the novel is because he saw a shade of his daughter Cecilia in her.

Something I keep coming back to is that we know people who can be cruel in socially acceptable ways. But when you go on these people’s social media, all their friends and family can’t stop talking about how marvelous they are. There is a way to switch off the loving and empathetic parts of ourselves and act in very different ways. Killers do this, too, to a much more extreme extent.

KB: How does the presence of Cecilia in the house change Rachel’s relationship to her captivity?

CM: Having Cecilia is a big help for Rachel. To survive for the five years that precede the novel’s start, Rachel has to numb herself to the memories of her past and her life outside. But in Cecilia, she sees shades of her younger, more tender self—the one that loved and was vulnerable.

KB: As someone also in this space (let’s call it feminist, literary thriller)—I often think about Truffaut’s claim that “there’s no such thing as an anti-war” film. I worry that all crime writing involving horrors against women turns the horrors into entertainment. Do you think about that at all? How do we wrestle with these ideas in a way that is complex and moral?

CM: The way I write about rape and sexual assault in the novel stems from reflecting on how to write responsibly. When we write about violent crime, I don’t think it’s inevitable that we will turn it into entertainment or make it titillating. But it’s a risk we run if we’re not careful. I wanted the book to be respectful of its victims—of the women and of what they’re put through. Also, I couldn’t go there. It made me uncomfortable. There is no draft where those scenes are more detailed. I was trusting the reader to fill in the blanks. Those scenes have plenty of menace and darkness in them. I don’t think it needs to be anatomical.

Those scenes work in contrast with other scenes in the novel. There’s a spectrum of non-consensual to extremely consensual sex in the book. There is a flashback involving Rachel’s boyfriend—it’s not consensual, but it’s not chained in a shed, you know? Every rape is a violent crime but every rape doesn’t look the same. And one person in a lifetime—and even a few months and even a couple of days—can have nonconsensual and consensual sex. The same man can be a perpetrator and a partner. That’s realistic. When allegations of rape surface against a man, we always hear: “he never did that to me,” or “he’s not like that.” But just because he didn’t do it to one person doesn’t mean he didn’t do it to someone else.

KB: There’s the negative space of the atrocities. Somehow, it’s more menacing to just see this man eating breakfast with understanding that he’s done all of these terrible things than to be dragged through all of them.

CM: It’s chilling, right? When I was writing those breakfast scenes, I thought: why am I spending three pages on this breakfast? Should we be spending so much time having breakfast with this man? But the answer is yes because the subtext is important. What’s scary is that he switches from doing these horrible things to making breakfast for his kid. That’s the thing we can’t make sense of. That’s the thing that is interesting.

KB: I don’t know if you ever watched Breaking Bad, but that show was famous for so much breakfast. But it was the crux of the show: How is this man who’s a meth kingpin sitting down with his kids and having breakfast? Same for The Sopranos, of which I know you’re a fan.

CM: Possibly the best episode of The Sopranos is the season one episode “College,” where Tony tours colleges with his daughter Meadow and ends up strangling a guy with piano wire. The absurd juxtaposition of Tony with his arm around his daughter’s shoulder, taking part in the time-honored family tradition of touring colleges—and even getting to be a cool dad because she comes back drunk and he doesn’t berate her—and then splitting his knuckles open while he strangles this man to his death.

In his podcast, Michael Imperioli said that HBO worried that fans would disavow Tony if he killed the guy—who is a rat, by the way. But David Chase said viewers would disavow Tony if he didn’t because of the codes of organized crime. So they ended up going with it. That’s why the episode is so gripping. Because we have the contrast between the two.

KB: And once you know his violent potential, it loads all of the domestic moments. In The Quiet Tenant, Rachel can watch Aidan eat breakfast, and as the reader, you’re nervous, because you understand that this man could flip on a dime.

CM: I read an interview where David Chase was saying —I paraphrase a bit—that he wanted to do The Sopranos because he was fascinated by the fact that mobsters don’t spend most of their day doing mob stuff. They’re not whacking guys eight hours a day. They’re caring for their kids, fighting with their wives, buying stuff, and having coffee.

That was a big part of my thing with The Quiet Tenant and why I wanted to tell a serial killer story in the first place. We think about serial killers as otherworldly machines, but in reality, they spend most of their time on Earth not doing what they’re infamous for. Usually, they’re not killing people. They are working their jobs, driving their kids to school, and in line at the supermarket. I’m fascinated by both the psychological duality and sheer logistics involved. I was trying to depict a serial killer as they exist in the real world. They’re usually just some guy. Some unimpressive person.

KB: I think this gets at a question I had about setting. “College”—part of the reason that works is because of the setting. How did you approach setting? The town and the house in The Quiet Tenant felt so claustrophobic, almost like detailed set pieces.

CM: I was interested in working with the smaller setting of a captivity story. I spent the first few months of the pandemic upstate in Rhinebeck at my in-laws’ house. We were home all day, and we could see what each of us did with every hour of the day. And I thought: what if one of us had a terrible secret we’d been able to keep because everyone else was away during the day? What if suddenly we didn’t have that distance anymore? What do you do with your secret?

I ended up basing Aidan’s house on my in-laws’ house. I based the town on their surrounding town, Rhinebeck. The town is lovely—it has a bit of a Gilmore Girls vibe—but the surroundings are spooky. Upstate New York has a particular beauty that lends itself to a thriller or a mystery.

KB: It’s funny—both Gilmore Girls and a lot of horror stories are set vaguely upstate. That setting can often gesture towards wholesomeness, but also you have Washington Irving and that dark, spooky Sleepy Hollow element. Which is the dichotomy between Emily’s version of events and Rachel’s version.

CM: I would go on runs on these deserted roads and see maybe one pickup truck for miles. It is gorgeous, but the nature is almost overpowering.

KB: I know you released a small press novel in French, in 2020, and it was not a thriller. What are the common threads that you see in your writing, across genre and language?

CM: My book in French is a literary novel about a female bodybuilder who ends up having to manage her sister’s bakery, which is a challenge for two reasons: it doesn’t give her time to train, and she doesn’t have the healthiest relationship with food. The bakery becomes a proxy for figuring out her own issues.

The books have a similar theme: bodies and how other people use our bodies to be cruel. The idea of control, the idea of trauma, the idea of male callousness. There’s a male figure in my French book, who isn’t Aidan. He is a well-intentioned guy who can hurt people without realizing it.

I’m happy that I had the experience of publishing something smaller before jumping into The Quiet Tenant. And then—I had the idea for The Quiet Tenant, which had to be a thriller. Most of my favorite thrillers are in English, so I decided it had to be in English. And here we are.

KB: In your mind, what works are in conversation with The Quiet Tenant?

CM: To write a captivity story in a world where Room exists is to be in conversation with Room. And what a formidable conversation partner. Room is one of my favorite books because it showed this incredible literary voice paired with this gripping story of crime and resilience and trauma. It blew my mind. And, of course, the film adaptation, for which I believe Emma Donoghue wrote the screenplay. There’s a moment that I watched a lot when I was working on The Quiet Tenant: the moment when Ma leaves the house. To me, that’s the emotional core of a captivity story in a few seconds.

A book that came up during my first round of edits with The Quiet Tenant was Misery by Stephen King. I hadn’t read it when I wrote my first draft, but I read it during revisions. It’s a captivity story, where the main character and captive Paul tries to do things undetected but also relies on his captor, Annie. He needs her to bring him food, but he’s trying to outsmart her. I ended up putting a little Stephen King easter egg in the pages of my book. In Misery, Paul uses his typewriter as a weight to regain his strength. And in my book, when Rachel is trying to regain her strength, the book she uses is IT.

All the books mentioned in The Quiet Tenant are easter eggs. The Andromeda Strain is a pandemic novel that I wanted to mention. Loves Music, Loves to Dance is about a nice guy who is secretly a serial killer.

The third book that I am in conversation with is a nonfiction book: The Stranger Beside Me by Ann Rule, which is the book she wrote interrogating her friendship with Ted Bundy. It’s extremely well-written. I don’t think she gets enough credit for her craft.

There are so many writers who showed me the way in terms of writing female-focused crime fiction. Jessica Knoll with Luckiest Girl Alive. I thought that was a mind-blowing book. Everything Megan Abbott has ever written. I adore her work. And I don’t think I would write what I write if I hadn’t read her books.

KB: What’s next? Are you working on another novel? Does it share any elements with TQT?

CM: I am working on something else, also in the psychological suspense realm. I’m very excited to have entered this genre and want to become more comfortable in it.

But it is funny—the first time you try to write something with the new ecosystem around you (agents, publishers, etc.), it’s a different experience. There’s something nice about doing it yourself because you’re doing it in the purest possible way. I was looking back on the first draft of The Quiet Tenant yesterday, and it was wild. Not formatted. No page numbers. One long stream-of-consciousness piece of writing. The most I did in terms of formatting: each new perspective was in bold. I forgot how casual the writing experience was for me. I was writing on my phone when I had 10 minutes. I was out there, having fun.

Hopefully I have a more polished process now, or more of an idea of what I’m doing. But I have nothing but admiration for 2020-Clémence, who was like, let’s go for it. Formatting? I don’t need that!