The invitation letter came twenty years to the day after the kidnappings. In 1999, guerrilla combatants from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia kidnapped my partner Terence Unity Freitas and two fellow land rights defenders. They were exiting Indigenous territory in Colombia—near land then coveted by a US oil company. Terence was a white environmental and Indigenous rights advocate from Los Angeles. He traveled with Ingrid Washinawatok El-Issa—native to the Menominee Nation in Wisconsin and executive director of the Fund for the Four Directions,—and Lahe’ena’e Gay—Native Hawaiian and the founder and president of Pacific Cultural Conservancy International. The three were working with the Colombian Indigenous U’wa pueblo. Eight days later, a farmer found their bound, hooded, and bullet-riddled bodies in his rainy cow field just across the Venezuelan border.

The timing was uncomfortable. The 2019 letter invited the families of the slain into Colombia’s post-civil war transitional justice process to participate as victims in Case 001, a cluster of cases involving thousands of victims of kidnapping.

In the original Spanish text, they sought our demandas de la verdad, our truth demands. The letter communicated that:

They wanted to know our stories.

They wanted to know our questions.

They wanted to put the voice of the victims in the center of the process.

They wanted to discern how to attribute criminal responsibility.

They wanted to give ex-combatants the chance to officially tell the truth or not.

They wanted us to use our rights to truth, justice, and non-repetition.

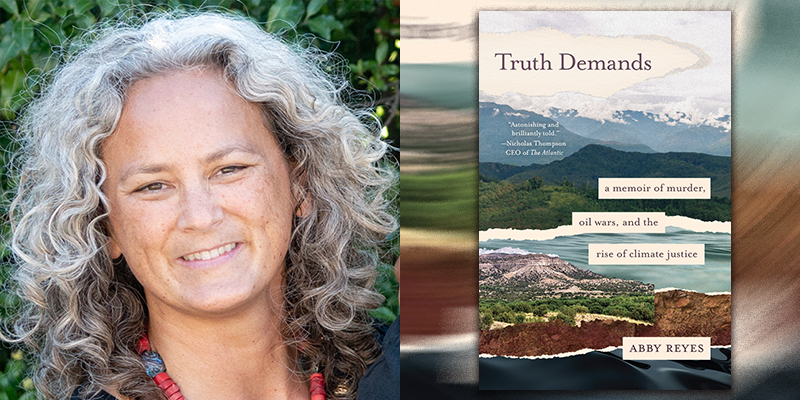

In the years following the murders, I felt pressed up against the machinery of fossil fuel extraction, tied there by the murders’ known and unknown dismal facts. I held fragments of stories for two decades, awaiting resolution that never came. To enter the Chamber, I needed to write them down. I wrote Truth Demands. Shaping the fragments into this book changed my understanding of resolution. Questions about the murders may always remain unaddressed. Some stories may never be told. And the future will remain unknowable. To offer this telling, I had to acquiesce to these truths. Acquiescence led to acceptance, which stirred my memory of agency. Finding agency in the telling led to my freedom, for it opened a back door to resolution.

As I wrapped up a draft of my memoir, I tackled the one remaining box in my closet. This box was the repository for documents that I tagged as important to revisit. Post-It notes scribbled with marginal insights, related articles, truth and recognition documentation, Terence’s papers, court filings—any document that remained untreated or that I feared I would forget. I made my way through the box swiftly, lifting helpful citations, details, and corrections into this text. I hummed through the work. I watched for the familiar dissociative fog to begin. It didn’t. I marveled at its absence, thinking I perhaps had made it solidly to the other side, to freedom.

I have.

This is how I know. The box contained a letter Terence wrote to me during a prior trip to the Indigenous territory, a letter within the pages of his journal. A letter he had never sent or given to me. In this letter, he stated his belief that the guerrillas had gone full-bore in support of oil development and that he felt that he faced threats because of it.

Over the past twenty-five years, in any forum possible, we have woven Terence’s posthumous observations into our questions about what happened. I was familiar with the letter. But when I picked it up again from the box, I couldn’t access my memory of those details. Instead, I experienced shock as though reading the letter for the first time. I was flooded with worry as though in a recurrent nightmare, one in which a missing key is revealed too late. That is how far my mind has buried pieces of this story that are the most threatening. In my shock, I called our legal team, worried that I had a new finding. They assured me that, yes, they knew this letter and had already integrated it into our work. I have no clear recollection of sharing the letter with them. Some past version of myself did, probably several times.

After talking to the legal team, I felt relief and gratitude. My nervous system started to re-regulate. With balance restored, I reread the letter.

I observed something in Terence’s writing. He wrote that even though he didn’t plan to send me this letter, he had “all of these thoughts wanting to come out, to be written so that I can rest”:

Unfinished ideas that are screaming to become more whole. There, they are written. The way that I would say them if you were here. The way that I am saying them aloud to you now, so that you will comfort me in my sleep.. . . It feels strange saying that. I don’t often feel the need to have someone else help me feel safe, moreover there are not many who could. You, your strength, makes me feel safe.

I was struck that Terence turned to writing to unlock rest. I was familiar with choosing this pathway for myself, but I hadn’t ever noticed that he did, too. A measure of the inadequacy of our support systems during those early years of walking alongside the U’wa, Terence, in essence, turned to his journal to stabilize his daily life on the ground.

His writing invited me to hold his words so that he could rest. In the normal course of things, this exchange—of words for rest— would be symbiotic. It would be an exchange that could expand into a community conversation. The burden would be shared. But our lives did not follow the normal course of things. He thought we had time. We did not. The murders stole time from us. I could see now that because this exchange happened only after he was already dead, it would go on to become, unbeknownst to Terence, the source of my own inability to rest for years to come. The clarity smarted. I gasped. Here was the source. I felt outraged. As was my practice, I turned to the woods to walk it out. I turned to the waters to dissipate, dissipate.

I have grappled with Terence’s words since I was twenty-five years old. To share the burden, I reshaped them into our truth demands and into this book. I have examined with care the exchange between words and rest. In writing my memoir, I have told the story of our truth demands as a way of learning how to stand on this wretched shore. Doing so taught me how to navigate home. In the telling, I saw glimmers of how we navigate our collective hearts back home, too. I am clear that I do not stand on the shore alone.

It is now twenty-five years later.

I let go of the words and I choose rest.

___________