“I dream I see blood.”

When she was 20 years old, Christy Pinnick came home and found her father, Ray Pinnick, dead on the floor of the kitchen of their Muncie, Indiana home. He’d been killed that cold evening in February 1994 while Christy was working the cash register at a drug store.

Nearly 30 years later, Christy is still haunted by what she saw that night. She talks about how she still has nightmares about finding her father’s body.

She still wants the men who killed her father to pay for their crime. That night, Christy is certain, those men who killed her father came into the drug store where she worked. She’s been told many times over the past 30 years, by people who knew her father and knew the men, that they had killed Ray Pinnick. She’s talked to police countless times. The men have not been charged.

Police investigators, crime scene technicians, emergency medical personnel and, in the worst scenarios, family members and friends of the person who was killed, have a unique perspective on what are widely known as cold cases. The family and friends who find their loved ones murdered will never get the image out of their heads. Sometimes it’s difficult for the professionals who work the crimes.

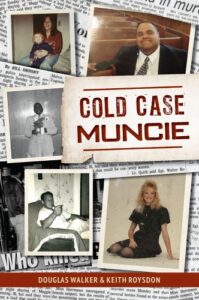

Cold cases are a popular form of entertainment right now, featured in podcasts and TV programs and yes, books, like the one Douglas Walker and I wrote, “Cold Case Muncie” our fourth true crime book published by the History Press. Stories about cold cases capitalize on the public’s fascination with crimes when a person has been killed and their killer isn’t brought to justice.

For survivors, being part of a cold case is a nightmare.

Anger, frustration over unsolved murders

In January 1997, I was pulling Saturday duty for the newspaper where I worked, filling in for the full-time police beat reporter. (Most of the past 30-some years that’s been my frequent collaborator Walker, whose knowledge of crime in Muncie, Indiana over the decades is encyclopedic.) I had heard that a body had been found in McCulloch Park, on the city’s northeast side. When I got there, I saw the victim, a young Black man whose body was on the ground near a railroad trestle. Snow had gathered in his hair and in the folds of his clothing.

I waited at a distance while police spoke to a woman who had heard about the crime scene and was worried that her son had been killed. She described him and his clothing and identified him as William Gene Burton. He was only 16 years old. She was angry and broken-hearted as she spoke to police, and her emotions were so strong that I almost had to look away. Her fury and hurt were almost more upsetting than seeing her young son’s broken body where it had been cast aside by his killer.

Twenty-five years later, in 2022, I interviewed Burton’s mother for a chapter about her son in our Cold Case book. The death of her son seemed nearly as fresh to her as if no time at all had passed since 1997. She cried and expressed anger and frustration that the killer had never been brought to justice.

If not for some emotional detachment, it would not possible for police investigators and coroners and even newspaper reporters to do their jobs. But what kind of person could see the crumpled form of young William Gene Burton, or of a loving mother like Maggie Mae Fleming, slumped on the couch in her modest living room, or the body of Charles Frank Graham, his cigar still clutched in the corner of his mouth, and not feel the loss of another person on the face of the Earth?

It’s a thing Walker and I and others who have written about cold cases and, much more importantly, those who have worked to solve unsolved murders, know very well. But grief has no expiration date for the survivors of those who have been murdered.

Murders in the typical small American city

That’s why we made a conscious effort to center the victims and their families for our book. We’d written about almost all the cases in the book over the years, in a series of articles for The Star Press newspaper in Muncie, Indiana. Because of a 1929 sociological study, Muncie, home of Garfield the cartoon cat and the university where David Letterman went to school, has long been considered the typical small American city.

It’s also a place with a high number of murders, including cold cases, over the decades. In the series of cold case articles, Walker and I had written about nearly three dozen unsolved murders, some dating back many years.

Almost all those cold cases had one thing in common: Surviving family members and friends who missed and mourned the person who was killed, and who still wanted justice.

Cold cases are shockingly common in the United States. The national murder clearance rate, the percentage of homicides that are solved, has over the years fallen to only about 50 percent, CBS News reported in 2022.

In writing about unsolved murders in our community, we found some that were still well-remembered – we wrote our third book, “The Westside Park Murders,” about the infamous 1985 slayings of two teenagers – and some are barely remembered. Over the years, we found, local police departments had lost or thrown away many murder case files. Others were ostensibly destroyed by flooding from broken pipes in police storage rooms. In many instances, the police investigators who originally worked the cases had long since retired or had died. Some family members had died, leaving no one to mourn or call for justice.

Women and people of color make up a sizable percentage of murders and unsolved murders. In our book, Calletano Cisneros not only mourns the 2009 murder of his son, Sebastian, but questions how hard police worked his son’s case.

From his home in a small town in Texas, the older Cisneros told us, “I looked up Muncie and it said it had something to do with the KKK and I thought, ‘Muncie’s not going to do anything. He was Mexican American and a drug addict.’” Police have always maintained they would never disregard a cold case investigation because of the race or identity of the victim.

Advocating for those killed

Several people we interviewed for the book said they feel like police investigators grew tired of their calls to advocate for their murdered loved ones. At the same time, some investigators told us about cases that haunted them, including one that’s not even been classified as a murder but as a disappearance. One veteran cop told us he’s convinced there’s a victim and killer in a case that most people don’t even know about.

In the book, we advocate for the creation of a “Cold Case Squad” of retired police investigators who would re-examine unsolved homicides. We met with a couple of retired cops who said they would take another look at old cases and we talked to the county sheriff in an effort to make it happen. Whether it will or not is hard to say.

One thing that might work against efforts to re-examine old cases is the number of case files that are missing, and we devote a chapter to that concern.

In the book, we include contact information for local police departments that have jurisdiction over the cases we write about. It was an easy decision to include phone numbers and contacts for police detectives: the investigators want to hear from anyone who might be able to help solve the cases.

The survivors of those killed also hold out hope. It’s why Calletano Cisneros spoke to us. He might be skeptical of how police handled his son’s killing, but he hopes that someone, somewhere, will have information about his son’s death and contact investigators.

“I just want some justice,” he said.

It’s the wish of every person who lost a loved one to a killer.

___________________________________